Netflix is turning the spotlight onto Fife and the horrific killing of Carol-Anne Taggart in its new season of the documentary series When Missing Turns to Murder.

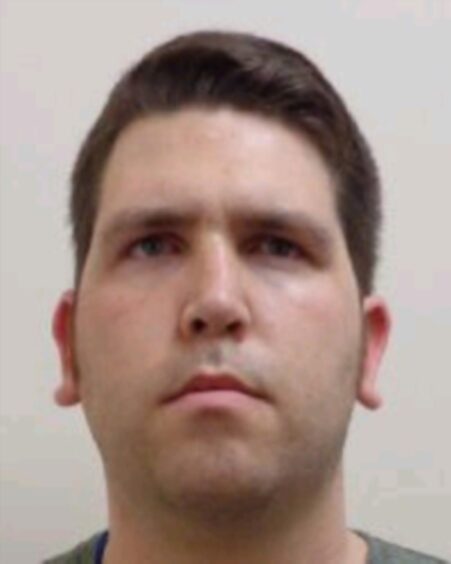

Carol-Anne was brutally killed by her own son, Ross Taggart, before her body was found in a Fife caravan park.

While the police were looking for her, he went shopping and on nights out with her credit card.

Taggart was convicted of murder in 2015 and sent to jail for a minimum of 18 years.

Justice may have been served in the court that day but not beyond it.

That’s because Ross Taggart remains the executor of his mother’s estate, which includes a house, a business and all her lifelong possessions from family jewellery to photographs.

While Scots law is clear that people cannot profit from their crimes, it is far from clear on the question of whether a murderer can be an executor.

Eight years on from his crime, Taggart cannot inherit his victim’s possessions. But neither can anyone else.

He is still exercising the power and control he used to kill his own mother.

And despite attempts from the family to raise awareness of the issue in the papers and with petitions, Carol-Anne’s name has never been uttered in the Scottish Parliament.

Fife killer Ross Taggart case shines light on gap in justice system

As far as I can see, no MSP has grasped the jaggy edges of this legal quagmire and sought to redress it.

In 2019 the Scottish Government consulted on the issue and then parked it.

A petition to change the law remains open on change.org. At the last count it had more than 62,000 signatures. That will surely grow with Netflix exposure.

The usual excuse for inaction on complex legal disparities like this is the need to wait for the right legislative moment.

Well as luck would have it, that moment is now.

The Trust and Succession Scotland Bill is going through the Scottish Parliament at the moment, with the Stage 1 process due to complete this autumn.

That’s the point at which the general principles of the bill are agreed by a vote of parliament.

However, the bill, as drafted, doesn’t really address the issue of whether it is wrong for a convicted murderer to be in charge of his victim’s estate because the Scottish Law Commission did not recommend the change.

It’s just another reminder of why Scotland needs a Victim’s Commissioner – something I called for more than five years ago.

We need someone who will inject humanity into the often dry, intellectual but obscure examinations of the legal system.

Someone whose primary focus is the citizen not the system.

Scotland needs a victim’s commissioner

I spent the best part of 10 years in the Scottish Parliament. And some of my most memorable moments there were spent with the victims of crime.

These fellow citizens, subsumed in their own grief, chose to relive the worst moments of their lives in front of a stranger like me in the hope that stranger might see the pattern, the fault or the horrors of a particular process and do something about it.

Listening to one father describe with quiet fury how he discovered the defence team for his son’s killer had a right to ask for their own post-mortem will never leave me.

It meant his precious boy had to be cut open twice in a mortuary, weeks apart, compounding his family’s anguish and delaying his funeral.

A Victim’s Commissioner, a post that commonly exists across the UK, would spend their working life on cases like that and cases like Carol-Anne Taggart’s.

It would end the drift and paper shuffling. The excuses. The culture of cases being everyone’s and no one’s responsibility.

Can Netflix – and Holyrood – end Taggart family’s pain?

The Scottish Government is committed to introducing a Victim’s Commissioner. It is legislating to do so just now.

That bill is also still at Stage 1, despite being in last year’s legislative programme and despite the idea being first proposed in Parliament in 2010.

It’s a pace so slow, a snail would be embarrassed.

Meantime, section six of the proposed new bill on succession creates a new mechanism to have an “unfit” executor deposed from their role.

However, this would still require another executor or interested party to file a court application.

Why should it be on the grieving family of Carol Anne Taggart to go to court to free themselves from the shackles imposed on them by her killer?

The Victim’s Minister Siobhan Brown was questioned about this by a parliamentary committee this week and said she would be open to going further.

All it will take is one MSP to draft an amendment which seeks to ensure no murderer can act as an executor to the estate of the person they killed.

One MSP, one line in a bill, one act of Parliament.

Who is going to pick up the mantle of this family’s pain?

An end to this awful endurance may be in sight. But it shouldn’t have taken a Netflix documentary to get us here.