Almost exactly eight years ago I watched as a burly, middle aged man held court on the banks of the Thames. Dusk was falling on the Palace of Westminster as MPs and their hangers-on gathered on the terrace overlooking the river.

It was one of those balmy, still summer nights when the tourist boats and pleasure cruisers gliding up and down the river were easily within earshot of the parliamentary banter.

I was a visitor to Westminster and observed as, at first, the man was joined by a gaggle of courtiers – mostly young, ambitious would-be adviser types – before the throng melted one by one until, finally, he was left alone.

Boris Johson then sat for a long time, entirely on his own at his table, gazing out over the Thames as darkness fell.

He may have fidgeted with his phone for a bit, sending or looking at incoming texts. I can’t quite recall.

But what I do remember very clearly is how solitary he was and how surprising it seemed that such a big beast of Westminster had, for a time at least, no one who seemed to want to speak to him.

Brexit changed everything

It’s easy to forget, however, just how far away from the centre of power Johnson then was.

He had just returned as an MP in the May 2015 election. This was before Brexit, before Covid, before Trump and before the war in Ukraine.

In truth it was a different world; not so long ago but at the same time impossibly distant given all that has happened since.

At the time, and despite his return to the Commons being seen by some as a relaunched bid to reach Number 10, Johnson was seen as a busted flush by many, even within his own party.

The prospect of him becoming Prime Minister seemed far-fetched. And maybe that explains his slightly forlorn demeanour that night on the Commons terrace.

What changed that of course was Brexit, and the decision he took to throw his weight behind the Leave campaign.

That choice is now widely understood to have been utterly opportunistic on his part, complete with two fully drafted newspaper columns, one for Leave and one for Remain, and an 11th-hour decision to plump for Leave driven almost entirely by personal ambition rather than principle.

Impacts felt far beyond Boris Johnson’s former seat

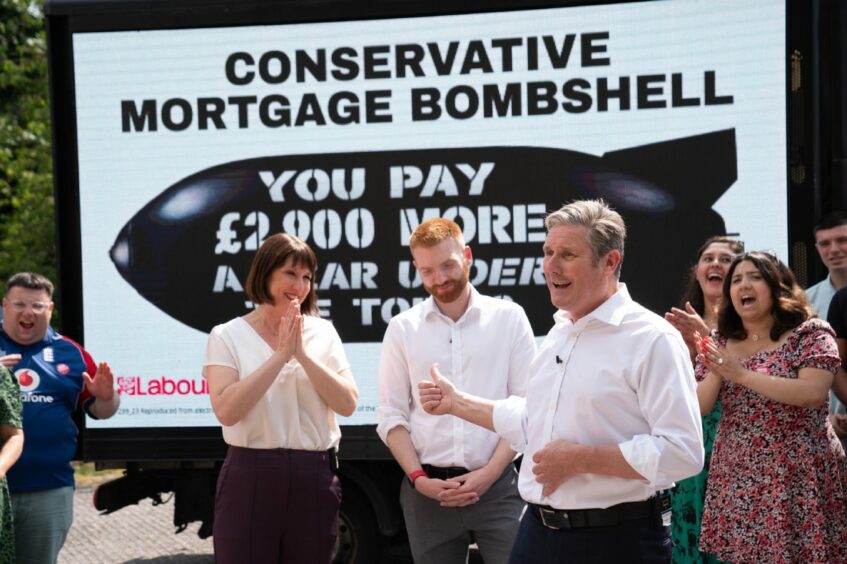

Two weeks from now the voters in Johnson’s former constituency will get the chance to decide whether to replace him with another Conservative as their local MP.

It will be a contest – along with other by-elections on the same day – which tells us much about how deeply the Johnson and Truss premierships have damaged the Tory brand, and just how badly the party is likely to fare in the UK general election expected next year.

It may also signal how they can expect to do here in Scotland.

Playing the anti-independence card for all its worth may be enough to shore up Conservative support in some of the Scottish seats they currently hold, but that’s probably as good as it gets for them.

The by-election in his old seat is also a moment to contemplate just how someone like Johnson, with his long history of being economical with the truth, was ever able to rise to the top of his party and become Prime Minister of the UK.

What does that say about the state of our politics, or perhaps more precisely and fairly, what does it say about the present-day Conservative Party and of a Westminster system which not just allows but enables and facilitates the promotion of such an egregious chancer?

Rise and fall brings us back to the start

Johnson’s tale is one of overweening ambition, opportunism, hubris and now, in the wake of his downfall, would-be vengeance.

As an avowed fan of the classics, he may or may not appreciate the extent to which his own rise and fall might be said to mirror that of the characters who populate the ancient tomes he is so fond of quoting from.

I think back to that evening in 2015 and wonder what he was thinking as he sat alone and stared across the darkening waters of the Thames.

That he had made a mistake in returning to the Commons? That he would never achieve his life’s goal of entering Downing Street?

Or, more likely by far, was he silently plotting how he could finally achieve that ambition and become PM?

The ancient Chinese proverb has it that if you wait by the river long enough you will see the bodies of your enemies float by.

The final irony for Johnson is that he could be there, waiting by the banks of the Thames still, and it would be the remnants of his own political life that he glimpsed drifting past.

Stuart Nicolson is a former political journalist and ex-adviser to Nicola Sturgeon and Alex Salmond.