Technically we are in the Year of the Rabbit, but it may well become known as the Year of the Protest.

Wimbledon is the latest major event to be hit with a Just Stop Oil demonstration, but there have been many others.

Few who witnessed it will forget the spectre of Johnny Bairstow, England’s wicketkeeper, hauling a hippy off the square at Lords cricket ground.

The hallowed felt of The Crucible was desecrated with orange dust, as was the Chelsea Flower Show – hardly a classic spectator sport.

Even the wedding of former Chancellor George Osborne was celebrated with a shower of orange confetti.

Scotland has had its own share of protest as well. Although, perhaps due to its geographical proximity to the North Sea versus Buckingham Palace, demonstrators have generally chosen to target the monarchy rather than ExxonMobil.

Earlier this month, four people were arrested outside St Giles’ Cathedral during a service of thanksgiving for King Charles.

It is tempting to view this age of protest as some kind of new phenomenon, spurred on by social media and a generation of woke activists.

This may be true in part. But it is absolutely not the case that protest – particularly dramatic and disruptive protest – is in any way novel on these isles.

Parallels in Churchill’s Dundee

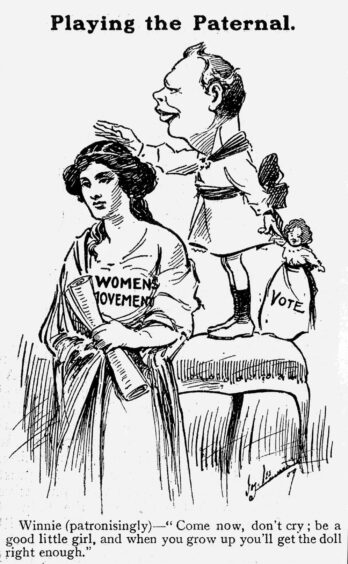

Winston Churchill’s experience in Dundee is a case in point.

During his successful 1908 by-election campaign in the city, he was famously pursued by a suffragette activist, Mary Molony, wielding a giant dinner bell.

Every time Churchill tried to make his stump speech, Molony would drown out his words with the ringing of the bell.

Churchill, meeting Molony’s eyes with a wry smile, eventually gave up and abandoned the meeting.

This was far from a one off, either.

In the December 1910 election, an Italian journalist, Luigi Barzini, was sent to cover Churchill’s campaign in Dundee.

After the count, he spotted Churchill’s motorcar surrounded by wary police.

“Are there terrorists about?,” an intrigued Barzini asked one of the officers.

“No,” the policeman replied, “worse, there are suffragettes”.

The question thrown up by these dramatic protests was the same then as it is today. Namely, to what extent is the disruption justified?

Often, the answer to this question depends not just on who you ask, but when you ask it.

Protests can’t be dismissed

No one today would quibble for a second that women should have the right to vote, or that the suffragettes were correct in their protests to pursue that right.

But back in the early 20th century, the issue was far more contentious and consequential.

Churchill, for instance, was privately supportive of the principle of women’s right to vote. Indeed, his wife Clementine – whose family came from near Kirriemuir – was a suffragette herself.

But Churchill would not publicly support votes for women because he believed the new female electorate would overwhelmingly vote for the Conservative Party over his own Liberal Party.

Similar nuances are currently at play when it comes to Just Stop Oil and, to an extent, anti-monarchy protesters.

Put simply, the balance of energy security and skilled jobs is pitted against the need to dramatically reduce emissions.

There are strong points on both sides of that debate today but looking back in 100 years our grandchildren may not see the same nuance.

With that thought in mind, and whatever our irritation, we should be wary of dismissing these protests out of hand.

Just Stop Oil protests lack impact of sugragettes

Another area where there is a historic parallel is the question of safety.

While many people will have been relieved that Bairstow finally caught something in this Ashes Test Series, it cannot be safe or sensible to have a situation where sports stars are hauling people off a pitch (perhaps why Just Stop Oil has, thus far, avoided targeting rugby or, indeed, ice hockey matches).

More serious still is the penchant for blocking roads.

We all know, of course, the awful spectre of suffragette Emily Davison, killed after throwing herself in front of King George V’s horse in 1913.

While no one would want a repeat of such an incident, the risk itself is not new.

There is, however, an issue with this current movement that separates it from its historical roots – and that is the manner of the protests.

The subtle and destructive beauty of Molony’s protest against Churchill was that she drowned out the voice of someone who was denying her a voice.

Throwing orange paint over a priceless and irreplaceable Van Gogh, or some orange powder on the wicket at Lords, does not have the same impact. It is wanton destruction masquerading as demonstration.

Perhaps then, while there is a historical basis for protest, there is not a historical basis for this kind of protest.

Either way, it is clear the Year of the Protest still has many more months to run.