GPs get a lot of stick.

And I can understand why.

From the 8am scarmble to the “not my department” bounce around, primary healthcare providers have earned the vitriol of the public and media alike in recent years, particularly post-Covid.

But the fact remains that no matter how poorly equipped, impersonal or rushed a visit to our city’s GPs are, we still need them. Big time.

A British Medical Association report updated yesterday reveals that a single full-time GP in Britain is now responsible for 2,305 patients – up 367 since 2015.

That’s a lot of people who need caring for, in every corner and community of this country.

But if we are not careful, we are going to lose this vital resource.

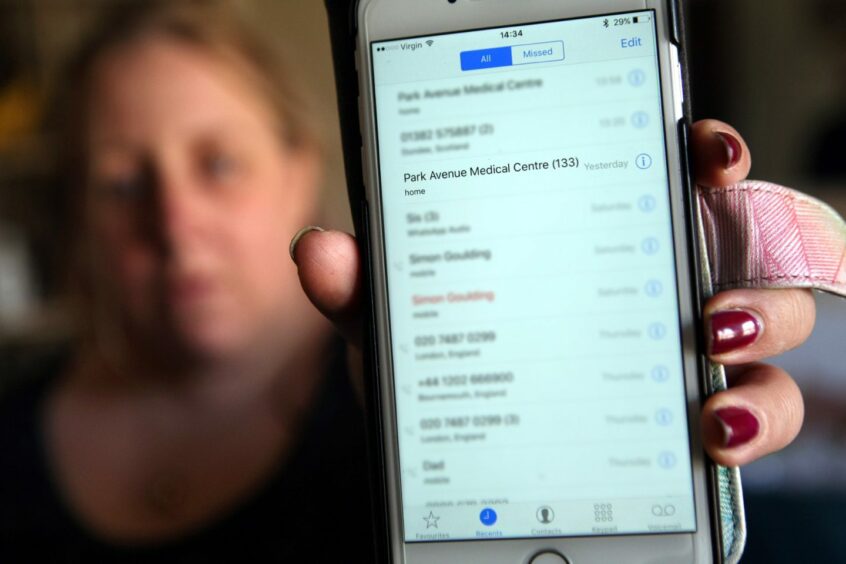

Case in point: This week, Dundee’s Park Avenue Medical Centre announced its imminent closure, following in the footsteps of Ryehill last year.

Stobswell and Wallacetown practices shut their doors in recent years too.

As a former Ryehill patient who was absorbed by another city medical practice, I know first hand how unsettling the process is, for staff and patients alike.

Any shred of interpersonal continuity with staff (rare as it is these days) is broken down. You become a number, an extra burden on an ancient, lagging IT system with the wrong phone number attached to your file (true story) rather than a person.

From the frantic looks of the reception workers, the gauntlet of probing pre-appointment questions and sharp refusals for new registrations I’ve observed since being ‘absorbed’, it seems like the city’s remaining practices have taken in all the strays they can manage.

Which begs the question, where are these remaining 5,000 Park Avenue patients supposed to go?

And, more importantly, how can we prevent this trend from continuing?

Why is there a GP shortage?

First, we must understand the reason for these closures: the ‘GP shortage’.

It’s is not as simple as a lack of funding (for which we could demand the NHS throw money at the problem) or a lack of demand (of which there is record levels).

Practices are closing because there are simply not enough doctors. And that is a much harder problem to solve.

It goes like this: an ageing population with increasingly complex needs and a stagnating rate of new doctor training makes for overworked and understaffed GP practices.

GP practices then become hugely unappealing places to work, with low morale and high burnout levels among staff, and extreme dissatisfaction reported by patients.

The title of GP is not now only thankless, but actively disparaged by a stressed, scared and increasingly sick public.

And in fact, the doctors want to be face-to-face with us just as much as we want to be seen by them.

But attempts by governments to patch the staffing issue using multi-disciplinary teams of paramedics, nurses and pharmacists to round out primary healthcare facilities have backfired, resulting in more admin and supervisory work for GPs as they train non-clinical staff on how to operate in a clinical setting.

This means less facetime with patients, and exponentially increasing frustration on both sides.

‘You couldn’t pay me enough to be a GP’

Who would want to work in an environment like that, I wonder? Well, student doctors are wondering the same thing.

As a mass exodus of existing GPs is caused by burnout, new doctors swerve to other specialisms in order to avoid such a fate. As a result, recruitment suffers, retirement goes up, and we live in a GP desert where people are going to A&E to receive treatment for minor ailments.

I’ve seen this happen in real time. Back in my Dundee University days, I shared a flat with a tenacious, high-performing and extremely compassionate medical student.

When she did her GP rotation, she eschewed the myth of ‘fat cat’ salaries and long lunches, telling me: “You couldn’t pay me enough to work there, it’s somehow stressful and boring. And the only person with any experience is leaving!”

She now works in a high-traffic A&E ward in a major English city, if you were questioning her threshold for stress. But boring I believe.

Add in a constant kicking from media types like me, and it’s no surprise no one wants to be a GP, and that the Scottish Government is nowhere near hitting its target of 800 new GPs in Scotland by 2027.

GP shortage is everyone’s problem

As a result of this vicious cycle, the stagnated, poor working conditions of GPs are about to be everyone’s problem.

Park Avenue shutting down will affect GP care all over Dundee. First and foremost for Park Avenue patients, who will be dispersed to unfamiliar clinics and forced to start fresh.

But also for every other NHS patient in the city whose already overstretched practice will be spread even thinner by absorbing the care load.

Dr Andrew Buist, chair of the BMA’s Scottish GP Committee, warned earlier this year that the GP shortage is “beyond crisis point”.

We don’t need any more specialist staff patching the holes, financial workarounds or elastic practices.

We need more GPs, plain and simple.