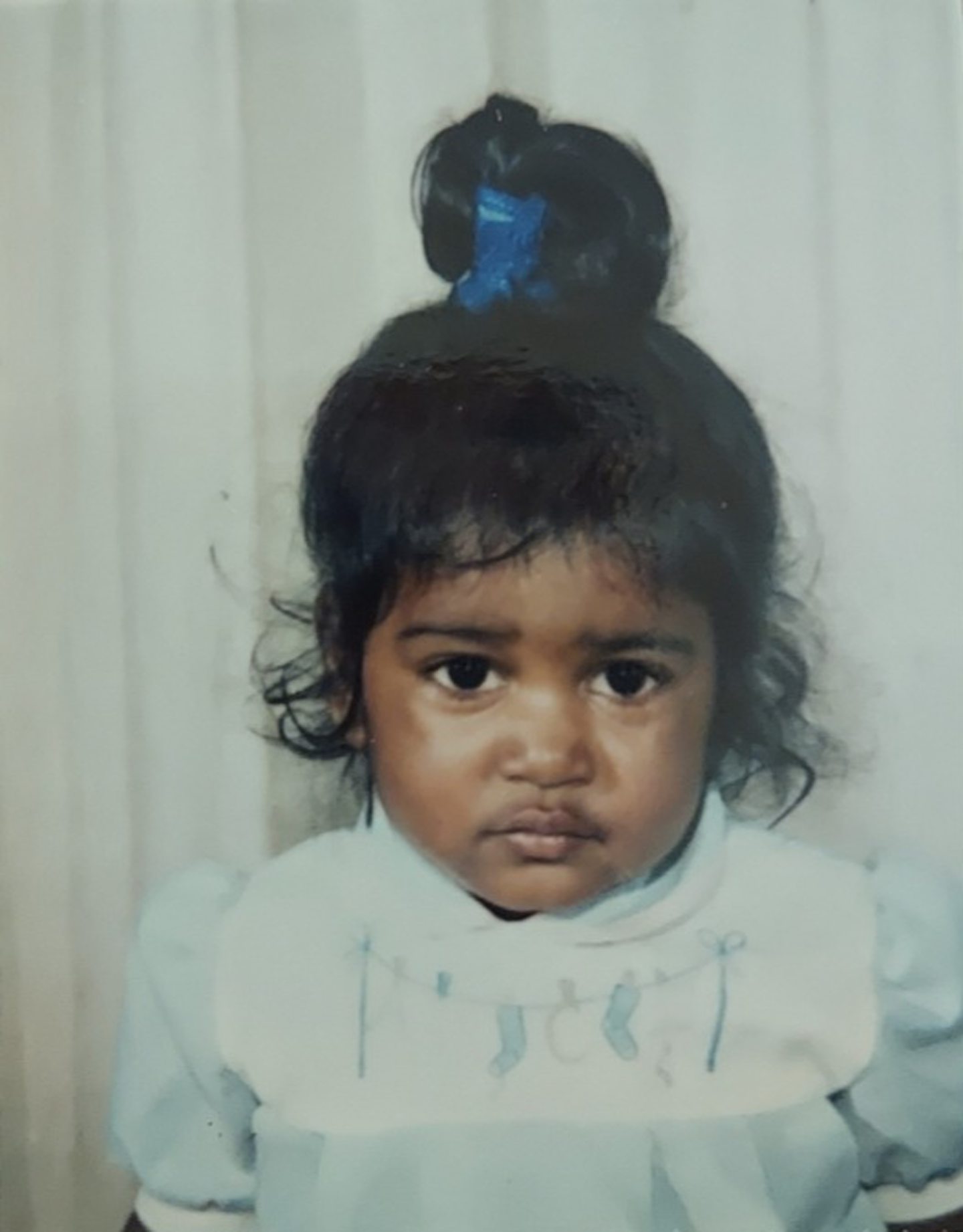

I was 10 months old when I was left in a field.

Old enough to understand I was alone but not old enough to run after who left me.

Luckily a passing family heard my cries and rescued me. I would spend the next few months and years being looked after by police, social services, the family who found me and a foster family.

For roughly the first nine years of my life I was raised by my adoptive parents in the Caribbean with UK trips to visit my adoptive parents’ biological children.

We eventually moved to Edinburgh and I went to school here, had my son here and made Scotland my home (we stayed in Leith for five years before moving to Dunfermline and then returning to Midlothian in 2021).

‘Better understanding required’

I am sometimes classed as a transracial or transcultural adoption, which means placing a child who is of one race or ethnic group with adoptive parents of another race or ethnic group.

Intercountry adoptee is another term used – that is the process by which you adopt a child from a country other than your own through permanent legal means and then bring that child to your country of residence to live with you permanently.

In a statement given by former First Minister Nicola Sturgeon at the Scottish Parliament on March 22, she apologised for the forced adoptions that took place in Scotland in the 1950s, 60s and 70s.

The Scottish apology follows Australia’s in 2013 and Ireland’s in 2021.

In her apology she also said specialist support and counselling services for those affected by historical adoption practices have been established.

I would also like to see her successor Humza Yousaf review forced adoptions in the 80s as well as looking into those involving children overseas who have been brought to Scotland.

We need to understand the services provided.

While we have more knowledge and support for adoptions and ethnic minorities, it’s still a grey area when they intertwine.

Issues raised are shot down

People don’t like talking openly about it unless it’s to portray the belief these children are “lucky” or the “adopted parents are saints for rescuing unwanted children”.

They often argue against any criticism of transracial adoption by saying it’s better than going into care, failing to see there are other options before adoption that may have been ignored or not offered.

For example, kinship care, where a child is unable to live with their birth parent and resides instead with a relative or other individual with whom they have a pre-existing relationship.

What about assessing the reasons the children can’t remain with family and whether or not those reasons – poverty, for example – can be addressed?

Other issues raised that get shot down are intersectionality in transracial adoption.

A lot of people don’t want to see race as an issue but for the transracial adoptee, it is a unique experience and deserves its own recognition.

Transracial adoptees from marginalised groups have similar issues as the forced adoptions discussed earlier, like falsified birth certificates and identities, but they also have the racial angle.

‘Traumatic experience’

In my case, I’m Caribbean and my adopted parents are white British.

Moving from the Caribbean to Scotland was a traumatic experience in itself.

It was after the murder of Stephen Lawrence and I remember thinking I had been brought somewhere where I could be killed just for the colour of my skin.

There needs to be more knowledge about the after-effects of adoption on children whether transracial, forced or other variations.

We need to stop thinking children are blank slates when it comes to adoption.

And we need to acknowledge the negative aspects to negate them becoming the serious issues in adulthood that we are struggling with today.

The Courier is a proud partner in the Pass the Mic media project, a platform which aims to raise the profiles of women of colour in Scotland and give a voice to their expertise.

The project was founded in 2019 and works with the women and organisations behind Gender Equal Media Scotland with support from Women 50:50.

Conversation