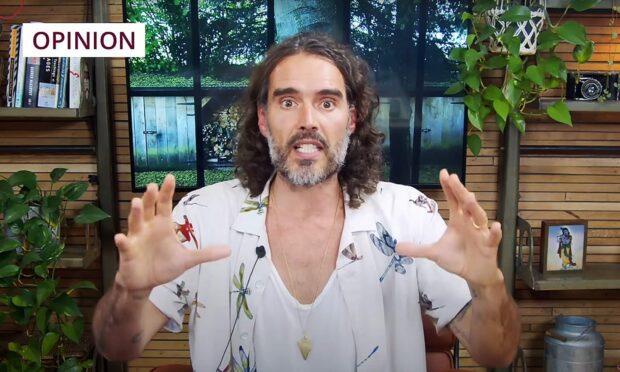

If the commentary around the Russell Brand allegations feels very familiar, that’s because it is.

Every time we see a high profile man accused of sexual violence, many people are quick to leap to his defence and cast doubt on his accusers’ claims.

It’s the same pattern we see followed in those accusations of rape that never hit the headlines; the same conversations that you will hear repeated in offices and living-rooms across the UK.

Because of the inevitability of these conversations, which are rooted in misogyny and victim-blaming, weariness can easily set in.

These last few days will have had a huge impact on victims and survivors of sexual violence.

When we ask, “why didn’t she report it at the time?” the answer can be found in the thousands of vile comments directed online at Russell Brand’s accusers.

It can be found in the horrifyingly low conviction rates for rape, figures which Victim’s Commissioner Dame Vera Baird previously described as us “witnessing the effective decriminalisation of rape”.

The answer to that question is clear: when you watch highly-paid broadcasters on breakfast TV pontificate about the veracity of the claims and ponder whether there is a risk that we are entering “trial by media” or “witch-hunt” territory.

Data is our friend and guide in almost every aspect of our lives, but not, it seems, when it comes to a crime which is entrenched in myth, misunderstanding and unconscious sexism.

False accusations of rape are not common.

Study after study has proven this fact. You are more likely to be raped than to be falsely accused of rape.

The investigation into the numerous allegations against Russell Brand was incredibly thorough.

It was conducted over a number of years. Multiple sources were interviewed, and their claims were rigorously vetted through freedom of information requests and the reviewing of phone, text and medical records.

The UK’s libel laws are notoriously strict and lawyers will have been consulted extensively prior to publication.

The Channel 4 Dispatches programme, Russell Brand: In Plain Sight, was an insightful and distressing look into the culture and conditions that allow powerful men to act with impunity.

Some of the details of the allegations – including those from a woman who was just 16 years old at the time she was in a relationship with Brand – are truly horrifying.

For his part, Russell Brand denies any allegations of criminality.

He says that this is all part of a coordinated plot to bring him down because he apparently speaks truth to power from the yoga studio of his £3m home.

The great and the good of social media’s woman-hating scene, including accused human-trafficker Andrew Tate, have rushed to Brand’s defence.

None of this is a surprise.

The women who agreed to be interviewed for The Sunday Times and Channel 4’s joint investigation will have been in no doubt about what would happen once the news broke.

They walked willingly into the eye of a storm, knowing that they’d encounter abuse, character assassination and hostility when they got there.

Perhaps they saw the disgusting bile directed towards the women in the film and thought that looked like a fun thing to be part of.

Or maybe, just as we saw with Harvey Weinstein and Jimmy Savile, women just find it easier to speak up about a high profile man when they know they are not alone.

‘Why is it that if a woman was drunk she was asking for it?’

It is interesting that much of the defence of Russell Brand’s alleged behaviour centres on the fact that he was, at that time, a self-confessed “sex addict”.

He has written extensively about his promiscuity and it became an integral part of the caricature that helped build his career.

Men can use their sexual history as a shield, but for women, it’s a chink in their armour.

A woman’s sexual history is often deemed relevant when she comes forward to report sexual violence.

This extends even as far as whether she was dressed ‘provocatively’ or had previously flirted or shown an interest in the man who harmed her.

This is one of the reasons why, despite the high-profile nature of these allegations, we shouldn’t set our hopes too high on seeing any real change come from it.

It’s a double standard that we see time and time again.

Why is it that if a woman is drunk she was asking for it, but if a man is drunk, he didn’t mean it?

A woman’s promiscuity is seen as a stain on her character. She isn’t to be believed, let alone sympathised with.

Yet when it comes to somebody like Russell Brand, the onus is placed on the women he encountered to have known better, rather than for him to have been a better man.