It is almost forty years ago, but the memories remain intense. A hospital corridor in Fife. The long, awkward wait. Groups of relatives, huddled together, eyes shifting awkwardly. Conversation hushed or non-existent. The silence penetrated by the sudden ring of the bell. The signal to confront what waited inside.

The shuffle through the ward was a welcome release after the tension of the wait. The mood lightened, conversation returned and a smile on locating your relative. For a fleeting moment, the illness that rendered the need for hospitalisation forgotten. Bedside, the sickness and claustrophobia returned.

I never enjoyed the visits – always longed to be elsewhere, away from the discomfort and the overwhelming smell of antiseptic. I think back to my demeanour in those final days – surly, detached, aching to return to the warmth and familiarity of home.

Longing to be out of this shirt I had been forced to wear, a shirt with a collar that itched to the point of madness. ‘Why do I have to wear a shirt?’ I once protested. ‘It’s not as if I’m going to church.’ ‘Stay here on your own then,’ my father spat back angrily and left.

I remember the feeling of relief. At the time, the cause felt just, the protest legitimate, my victory significant. Now, I realise that he was likely too crushed to argue. The petulant child in front of him an inconsequence to the gravity of the situation he faced.

I don’t know how I used my reclaimed hours, probably watching television or playing games alone. That memory has faded, yet the imagined conversation between my parents as to why I wasn’t there burns vividly. It is a thought that shames me.

Yet, I know it wasn’t my fault. I was twelve years old, impulsively childish and had been kept in the dark about the magnitude of what was unfolding. For me, it was just another visit until she came home. The thought that she would never return and that this was a series of rapidly diminishing opportunities to be together completely absent from my thinking.

‘I learned about her death by accident’

I was never told directly in the end. The first realisation that my mother’s death was even possible gleaned from the accidental overhearing of a conversation. The quiet whispers magnified to an oppressive roar when the discussion turned towards how to cope after she was gone.

Nothing could protect me from the brutality of the final word. There were no more visits. Dad went alone in those last few days. Years later, our GP would admit that the hospital had been at fault. An infection picked up on the ward complicating a routine operation. It had been entirely avoidable but, in the moment, we were too preoccupied with the loss.

Initially, I tried to carry on. High school was about to return and I was insistent that I didn’t want to miss the first day. It was a naive thought, but it was indulged and I left for a friend’s house to prepare. After a few hours of sleep, grief intruded and I woke distressed, crying and had to be returned home. Normality would have to wait.

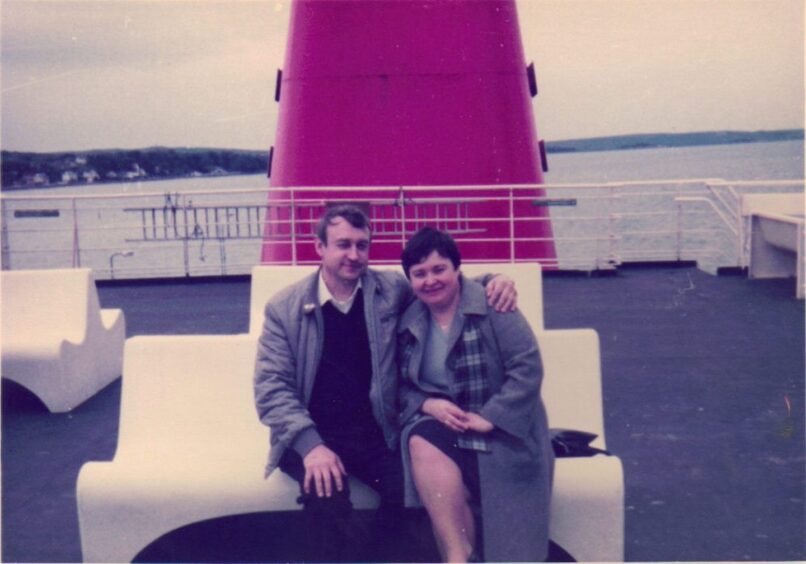

The days before the funeral brought relief. Our family was from Northern Ireland and the influx of relatives from Belfast became a welcome distraction. A solemn undercurrent flowed, but the mood was one of reunion and reconnection. Sentimentality, humour and alcohol flowed freely. The traditional Irish way to distract each other from pain. The funeral complete. Relatives left and life resumed. There was no discussion of grief, just a stoic resolve to move forward.

‘At first, I treated the death like a badge of honour’

As time passed, I moulded the loss into a strength. I’d been a naive, immature child who was far from streetwise. The loss of a parent made me grow up quickly, it brought resilience and handed me an ability to face anything, or at least that was the story I shaped in my head.

It became a badge of honour that I brought out to show people my character, my strength and, occasionally, to invoke sympathy. ‘That must have been really difficult.’ ‘Yes, yes, it was,” I would reply knowingly, ‘But I got through it and it has made me stronger.’

The illusion could be punctured in an instant. I recall an early conversation at university where a fellow student told a group of us who received a full student grant that we were the lucky ones. She was unknowingly telling me to be grateful for my loss. It was an unthinking moment of self-pity from her and the intention was not to wound, but it did. I returned to my room and sobbed.

Grief could seize me even in happy moments. After the birth of our daughter, I phoned the mum of a school friend to tell her the news. She had been one of the people who had stepped in with kindness when my mother had died. She did it quietly, unnoticed at the time, but I now recognise her small gestures as deliberate acts of compassion – the tolerance of me being in their house for hours, the invitations to stay for dinner or to tag along on family days out.

When I told her that we had given our new-born daughter my mum’s name as a middle name, the loss flooded in. I finished the conversation quickly, then broke down.

‘Her death left me insecure and lacking in confidence’

Yet moments like this were rare. I made my way through life in a blur of activity, progression, and fake resilience. I built a relationship, a family, a career. The standard measure of a successful life.

It was only when forced to press pause in early 2020 that I began to seriously reflect on what I had faced over thirty years earlier. ‘It was childhood trauma,’ a friend suggested. My instinctive reaction was to laugh. ‘Don’t be daft,’ I replied.

To me trauma involved something far worse, violence, war, suffering at the hands of an abusive adult. I had just lost a parent. Even the phrase minimised the experience, reducing it to something akin to dropping a glove or mislaying a set of keys.

It took conversations with a counsellor to confront this false narrative. Exposed to the light of day and under scrutiny, I realised that the death of my mother had left an ominous shadow and an unwelcome inheritance.

My insecurity and lack of confidence. My longing for constant reassurance. My desire to be liked. My relentless high standards and destructive self-loathing when I failed to meet these. My learned reliance on food to smooth off the edges creating a lifelong struggle with weight. My fatalism that I will inevitably meet a similarly catastrophic end, that to this day sustains a lack of physical and emotional self-care. These had all shaped my life and continue to do so.

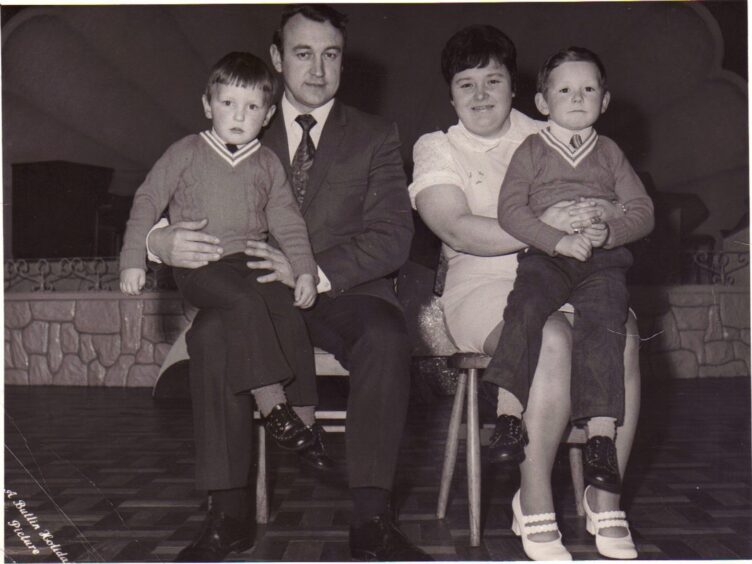

It is now 39 years since my mother died, that number imbued with a morbid significance. She was 39 years old when she passed away, mockingly short of a marker when society tells you that life begins. I still think about how life could have been different.

‘I no longer present a façade of resilience’

The moments and milestones we could have shared over the years. The warmth and love she would have had for my daughter. I think about how I was left alone as a child to deal with the loss, not wilfully or cruelly, but because it was how society dealt with grief at the time. If I’d been given support, encouraged to vocalise my hurt, heard the insight of others who had experienced similar, perhaps I may have been able to better process the loss.

That is what I am at last attempting to do, thankful that I no longer have to present a façade of resilience. I heard the Scottish poet Michael Pedersen read a poem in the aftermath of the loss of his friend Scott Hutchison. He spoke a line that resonated deeply. ‘You’re gone and it’s not, nor will it ever be, ok.’ His eloquence captured the endurance of grief. It can soften, but it will always have the capacity to bring pain.

The death of my mother hurt. It still hurts. It will always hurt. And I think I’m finally learning to live with that.

Conversation