Victims of violent crime should always be more important than those guilty of committing the crime.

When it comes to deciding whether parole should be considered or granted to those who have committed heinous and brutal acts of violence, their rights should be at the very bottom of the long list of issues that should concern us.

The innocent whose lives have been violently traumatised must always be at the head of the queue when it comes to justice.

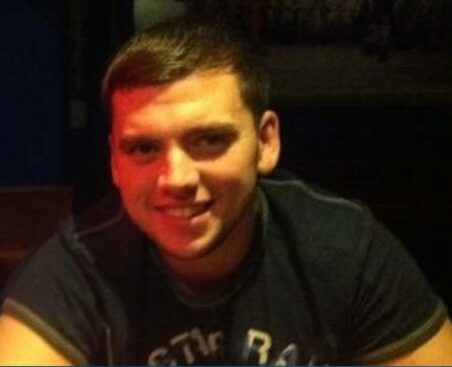

This week the parole board will consider the case of Tasmin Glass who has served less than five years of her 10-year sentence, after her conviction for culpable homicide in her part in the shocking murder of Arbroath oil worker Steven Donaldson.

She should serve her entire tariff, no ifs no buts, and if she doesn’t it will confirm that the parole system isn’t for purpose, is skewed in favour of the guilty and the cruel, and is manifestly unjust towards victims and their families.

There’s never an easy answer to what constitutes justice, but once properly convicted and sentenced in a court of law, the rights of those guilty of vile crimes must come far behind those of the innocent when deciding parole.

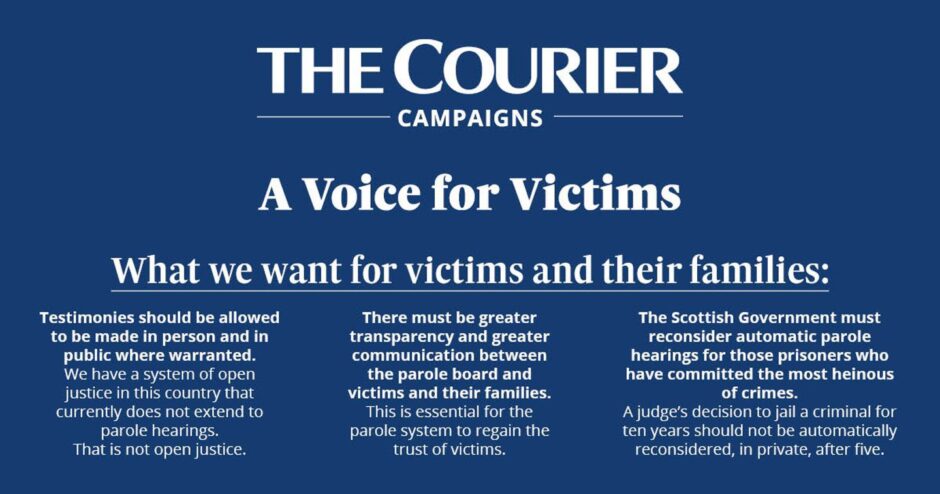

That means as the current Courier campaign demands, testimonies from victims and their families should be heard in person at parole hearings.

It means proper transparency for victims and their families on decisions and findings of the parole board to ensure trust in the system.

And that no automatic reconsideration of reducing a sentence of 10 years in less than five, as in the case of Glass, should be taken in private by a parole board.

Most folk will hopefully never suffer from serious violence, but the horrors and ramifications of such grotesque actions last a lifetime for victims and their families.

I wrote in May 2022 that the Dundee killer Robbie McIntosh should never be released.

He was out on home leave in 2017 while serving a life sentence for the brutal murder of Anne Nicoll, whom he’d stabbed 29 times on the slopes of the Law, when he was aged just 15.

While out he attacked Linda McDonald in Templeton woods and battered her with a dumbbell.

I remember Linda telling me that as she fought for her life she’d looked into the eyes of the devil.

A review in 2019 into what went wrong in allowing McIntosh out of prison to almost murder again found that a psychological assessment in 2012 had shown a high risk of him re-offending.

Yet the report also added his attack on Linda McDonald “could not have been predicted’

Those two statements show the inexact science behind the parole system.

There’s no crystal ball which can guarantee the behaviour of someone as cold and calculating and as disturbed as someone like McIntosh.

Similarly there’s no guarantee of future good behaviour from Tasmin Glass, who was convicted of instigating and planning the attack on Steven Donaldson, whose battered and burned body was found next to his car at Loch of Kinnordy Nature Reserve, near Kirriemuir, on June 7 2018.

He had been assaulted at the town’s Peter Pan playpark by her co-accused Steven Dickie and Callum Davidson, who then drove him to the nature reserve where they killed him with a bladed weapon.

Both were convicted of murder and given life sentences.

Glass got off lightly with a 10-year sentence in my view.

“She was the prime mover behind the assaults on the deceased,” said Lord Brodie, one of three judges to reject Glass’ 2019 appeal to reduce her sentence.

She was art and part in a despicable and revolting crime which left an innocent young man dead and his family bereft.

As Bill Donaldson, Steven’s dad, told The Courier: “Our sentence is for life, we will never be set free”.

Any civilised society must operate within the rule of law and it’s right that we consider, along with the idea of the deterrence and punishment elements of sentencing, the possibility of the rehabilitation of offenders.

But when it comes to parole and everything connected to the decision making in it, we cannot simply leave it to unaccountable panels.

‘Advantage must be given to victims and families’

We shouldn’t entertain notions of revenge, but the balance of the advantage must always be given to the victims and their families.

Their views should be given ample weight in decision making.

That doesn’t mean they make the final decisions but should mean as much substance as possible is given to their testimony and concerns.

There are among us folk capable of great evil and wrongdoing.

When it comes to parole of such folk who have been convicted of gross and unimaginable acts of cruelty and violence, their interests must be secondary to societal norms of decency and fairness.

Conversation