With Halloween upon us, Fife Council archaeologist Douglas Speirs speaks to Michael Alexander about the macabre history of grave robbing in Fife, Tayside and beyond.

Sneaking into the 15th-Century East Neuk of Fife churchyard under cover of darkness, the grave robbers dug down into the lair of local ship owner and farmer Stephen Williamson until the crunch of bone confirmed they had reached the former magistrate’s mortal remains.

A spade was used to dig down five feet, where Mr Williamson’s skeletal remnants from 1816, and those of his wife Mary Grieve, who died in 1828, were then cut through and fragments of bone dumped in soil on the surface.

The callous, gruesome vandalism might sound like a vile act from the days of notorious 19th century murderers Burke and Hare.

However, the macabre desecration, which brought hurt and distress to descendants and the community, actually took place in March 2015 when the grave was vandalised in Kilrenny Church yard near Anstruther.

“If they thought they were going to find valuables in there, they would have been disappointed,” a member of the deceased’s family told The Courier when eight descendants from across the world gathered with 17 East Neuk residents a few weeks later to re-bury the bones in a specially-made small casket.

The Rev Arthur Christie, minister for Anstruther, Cellardyke and Kilrenny, who gave a Celtic blessing at a service to “bring peace and healing”, said at the time he was “at a loss” as to why someone would do this.

“We’ve all seen vandalism of some description over the years but we’ve never experienced desecration of a grave,” he said, adding that the coffins of the deceased had long since decayed and only the bones remained after centuries of peace.

Thankfully, such grossly disrespectful acts of destruction to ancient graves are rare.

However, bizarre as the incident was, there was a time when grave-robbing and body-snatching was more commonplace across Scotland as medical science fuelled demand for fresh corpses.

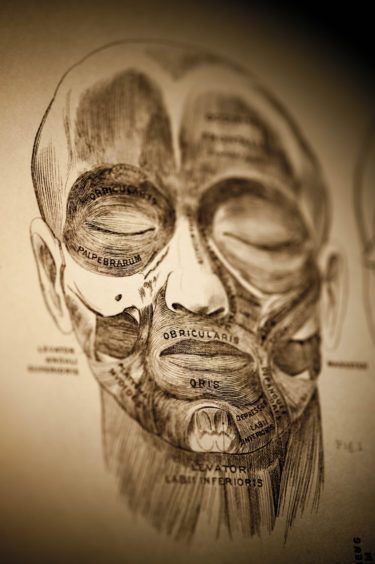

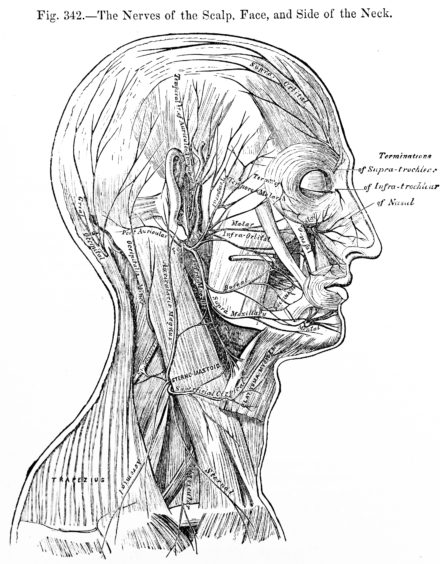

Fife Council archaeologist Douglas Speirs said that whilst early surgeon-barbers, apothecaries and university anatomists dabbled in human dissection from an early date, the study of anatomy in Scotland as a branch of medical science dates only from the closing years of the 17th century.

“While it’s true that a charter granted in 1505 to the Incorporation of Surgeons and Barbers in Edinburgh stipulated that every candidate for admission should ‘know the anatomea, nature and complexioum of every member of manis body’, it was not until 1694 that an agreed and legal mechanism for the limited provision of bodies for dissection was agreed between Edinburgh’s burgh council and the town’s Incorporation of Surgeons and Barbers,” he told The Courier.

“The subjects thus made available were extremely limited in number and were restricted mainly to the ranks of unclaimed executed criminals – usually only murderers – unclaimed suicides and foundlings.

“Petitions lodged both before this time and after for permission to “open the bodies of those unclaimed souls who died in the poorhouse” were refused on moral grounds and the inability to secure subjects for research perpetuated the established tradition of Scottish students going overseas, mainly to Holland, in order to study anatomy.”

Mr Speirs said the picture was slightly improved in 1752 when in response to an increase in the number of murders, particularly in the London area, the Act for ‘better preventing the horrid crime of murder’ was enacted.

For the first time, this change in the law granted judges the discretion to order that an executed criminal be delivered to surgeons for dissection.

Indeed, the new law stipulated that on no account was the body of a convicted murderer to be allowed a proper burial unless dissected first.

The motive behind the Act was of course not a desire to further the interests of science but was in fact a further punishment designed to deter would-be murderers from action – not only would they be executed, but their corpse would be mutilated for eternity in the afterlife.

In 18th century Scotland, the rise of the professional, apprentice-trained doctor-surgeons led to a dramatic increase in the demand for human dissection.

Edinburgh led this growing trend in 1704 with the appointment of Mr Robert Elliot as the university’s first “public dissector in anatomy”.

In Glasgow, human anatomy was taught at the university by Thomas Brisbane from 1720 onwards whilst in Dundee (originally part of St Andrews University), Thomas Simpson, began public dissection classes in 1722.

Scotland, however, still lagged far behind the anatomy schools of Europe and in every case the problem was the same: the extreme difficulty in obtaining bodies for dissection.

Yet, by the later 18th century it was apparent to many that the country’s numerous universities and private medical schools were consuming considerably more bodies than could be supplied to them through strictly legal agreements.

“This situation had not escaped the attention of the authorities and in truth, a blind eye had been turned for many years to the way in which university anatomists, usually with the help of inebriated apprentice-students, had been clumsily removing freshly buried pauper bodies from local churchyards,” said Mr Speirs.

“Before the 1780s, when the numbers of such incidents was relatively small, little or no attempt was made by these first body-snatchers to hide the evidence of their work and contemporary newspapers report with surprising indifference the occasional appearance of large holes in cemeteries and smashed-up empty coffins.

“But by 1810, things had changed. The demand for bodies had far outstripped the numbers that could be secured through the amateur work of students and masters alone. Indeed, demand had created the illegal profession of securing bodies for sale and public and the authorities were now wise to what was going on.”

Mr Speirs said it’s fair to say that the opening years of the 19th century were characterised more by body-snatching than by grave-robbing.

Body-snatchers specialised in appropriating bodies to which they were not entitled but they didn’t actually dig up buried corpses.

They might give false testimony in order to appropriate the bodies of deceased travellers, itinerants or the unclaimed poor and elderly.

Purporting to be relatives keen to claim the bodies of a distant loved-one for proper burial, their real intention was of course a late night visit to the back door of an anatomy school.

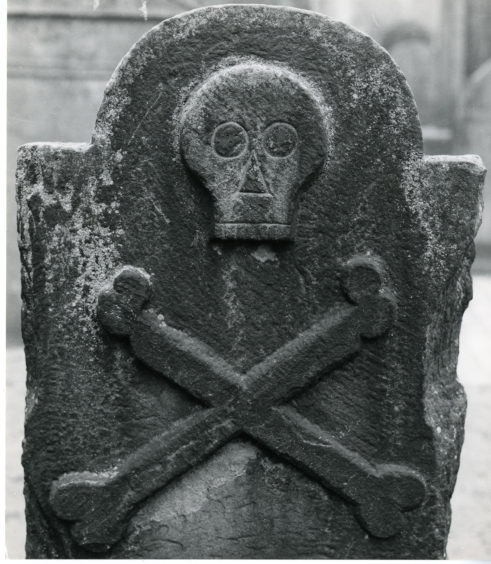

Grave-robbing, on the other hand, was, as the name suggests, the practice of illegally digging in cemeteries for the bodies of the recently buried.

To contemporary Christian sensibilities, both practices were viewed as morally heinous crimes but stealing from graves was by far the greater of the two evils, said Mr Speirs.

“Whilst the authorities watched on and did little, the parish ministers of eastern Scotland acted with vigour,” he explained.

“It’s not an exact evolutionary trend but in general terms, recognition of the threat of grave-robbing was greeted in Fife and Tayside from about 1814 onwards by three physical responses: mort-safes, then watch-houses and finally mort-houses.”

Body-stealers had to work fast and the most common technique was to dig a small trench downwards at the head end of the grave, smash open the end of the coffin and then remove the body by means of attaching a rope around the neck and pulling.

In such a fashion an experienced team could remove a corpse from its coffin, back-fill the hole and be off within an hour without anyone being any the wiser.

Mort-safes were therefore designed to secure bodies from theft: iron cages around coffins or over graves, wooden coffins reinforced with iron bands, stone and iron coffin casings and a wide range of iron fixings designed to pin or chain a body to its coffin are known.

When this was found not to work, watch-houses began to be built to watch over parish churchyards.

This involved greater capital expenditure and it was not always effective as the costs of watchmen had to be met and at the prices paid to them, it was often difficult to keep them sober or free from bribery. Thus, the mort-house was finally adopted.

“Much of the evidence for corpse protection still lies buried in our churchyards,” said Mr Speirs, “but the digging of later graves has uncovered many mort-safe contraptions including coffin-collars from St Andrews, Monimail and Kingskettle.

“Mort-stones, however, remain the most commonly encountered form of mort-safe and many can still be seen today. These are large, coffin-shaped stones usually with an attached iron grille.

“They were laid on top of the buried coffin, the stone resting on the coffin lid and the iron grille extending downwards in the form of a cage around the coffin.

“After several weeks of burial, when the putrified body was of no interest to the grave-robbers, the mort-stone would be excavated, removed and readied for re-use.”

With over 19 watch-houses still in Fife alone, Mr Speirs said it’s easy to see that this form of protection, dating mainly from the 1820s and 30s, was a favourite.

Some such as the watch-house at Liff remain unaltered whilst the conversion of others, such as that at the Howff in Dundee, hides their original function.

Watch-houses were not infallible, however. Relatives could not always watch over the graves of their loved ones and hired watchmen were notoriously unreliable.

Absence from their posts, drunkenness and even collusion with the body-stealers is well recorded.

Mort-houses, literally houses of the dead, were the final physical expression of the public’s demand to see their loved ones rest peacefully in their graves.

Larger than watch-houses, these thickly-set, stone-built buildings with reinforced doors and iron-barred windows were designed as secure resting places into which bodies could be placed before burial.

The idea was a simple one. Anatomists needed fresh bodies.

Mort-houses allowed for a secure environment in which a body could be left to decompose until it was of no use to a body-stealer, at which point the body could be removed and buried.

Good examples of mort-houses can be seen at Rosyth and Abdie in Fife but Crail has an unusually fine example, built in 1826.

Changes in the law and easier access to a legal supply of bodies eventually led to the end of the era of the resurrectionists and the infrastructure fell out of use.

Mr Speirs said it’s true that in reality, graves were not routinely robbed in Tayside and the response, particularly in Fife, was “hugely disproportionate” to the actual reality of the problem.

However, he added: “The fact that so many of Fife and Tayside’s churchyards still retain some physical trace of a response to the fear of body-stealing, is testament enough to the extremely widespread fear of the possibility.”