Vixy Rae remembers flicking through a dog-eared copy of a Jackie Annual in an Oxfam shop back in the 1970s.

“The photos of the tartan-clad Bay City Rollers intrigued me and repulsed me,” the clothing designer recalls in her new book The Secret Life of Tartan: How a Cloth Shaped a Nation.

“For me, at this time, it was easier to dismiss tartan altogether; it was best left to the tourists, the punks and the ageing glam rockers.”

Born and raised in Edinburgh, she started out in the Old Town selling branded skate and street wear and going on to open a second store in Glasgow and running her business for 14 years..

“When the internet age began, I stepped back from buying other brands, because nothing was exclusive any more, and the concept of my store died over night,” she explains.

“Always having a passion for craft and local sourcing I quickly became disillusioned with the majority of cloth and garments being made overseas but sold as ‘Scottish’.

The opportunity to co-own Stewart Christie & Co (Scotland’s oldest tailor) was a dream come true for Vixy and it was here that her passion for tartan was ignited.

“The company has served gentry, nobility and royalty over the three centuries it has been trading, and I am ashamed to say my grasp of families, clans and tartans was not as good as it could have been,” she admits.

“But with so many ladies coming to me wanting to create unique pieces made from their family tartan, I began to develop an understanding and this led me into looking at the past to realise the potential of the future.

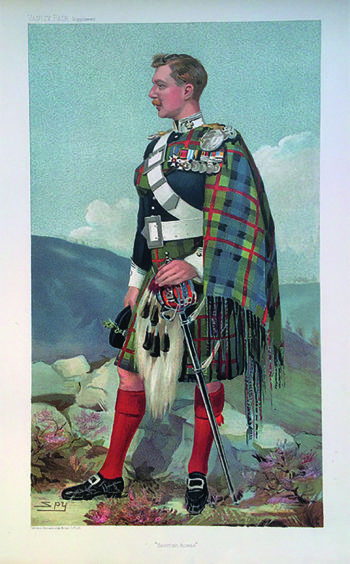

“Tartan is intrinsically a masculine cloth associated with kilts and burly highlanders, but I try to evoke the feminine in my creations, using the definite lines to echo the female form.”

The book features the people behind the cloth – the families, weavers and designers – and took Vixy around six months to research and write, a period she describes as a fast and steep learning curve.

“My research started with the people who have a passion for the cloth, either in the way they create it, study it or use it, and from there the stories of the chapters evolved. For me, associating people with each chapter was the obvious way to write and tell the story of the past and the present looking into the future,” she says.

“I wanted to create a book which was not a text book, but it had to contain facts and stories so it could be useful, weaving together the delicate and sometimes mythical past of the hallowed cloth. Something for all ages and something to evoke more questions about how Scots purvey and purchase, or buy into the legends of the past.”

Vixy reveals that there is no fixed answer as to the origin of the word ‘tartan.’

“‘Tartarin’ was the French word for a coarsely woven cloth of blended wool and linen. Then there is ‘tiritana’ from the Old Spanish – it’s the word from the Old Spanish – it’s the word for a silk fabric, from ‘tiritar’ meaning to rustle,” she explains.

“I prefer the Gaelic claim, coming from the words ‘tuar’ meaning ‘colour’, and ‘tan’ meaning district, matched with ‘tarsainn’ meaning ‘across’. This beautifully supports the theory that from early times the cloth was a recognition of region rather than clanship.

“Unfortunately there is no documentary evidence to support this evocative claim.”

During her research Vixy soon discovered layer upon layer of intricacies in the history of tartan.

“It was probably understanding how it was made in the early days and who made it which surprised me most,” she reflects.

“Before the industrial revolution tartan was mostly made by crofters and each town would have had their own ‘weaver’ or ‘webster’. These people would have had a skill handed down, and one of the biggest surprises was realising that to achieve consistency over pieces was incredibly difficult as natural dyes would take differently to different yarns so even the colour making was an art form,” she continues.

“Horizontal looms required an apprentice to throw the shuttle across the weft but with more mechanised looms it could be operated by one man. Today everything is so easy to get hold of – back then a ‘new kilt’ meant a lot of different aspects.”

Vixy believes that tartan has as much relevance in the modern world as it ever did.

“Today tartan still brings people together, unites us across the globe and is still quintessentially Scottish,” she says. “It is one form of national dress which is completely recognisable and one which people the world over want to try out and wear and be proud to be a part of,” she says.

“It still is hard to believe that across the world the Scots have made impacts in so many ways. With today’s obsession in the western world with finding our ‘roots’ and tracing our heritage back, when people find associations with Scotland is brings a sense of pride and belonging and they often feel the need to show this by wearing tartan.

“In a sense I guess it is like a private member’s club where you have to have a blood line rather than money to join.

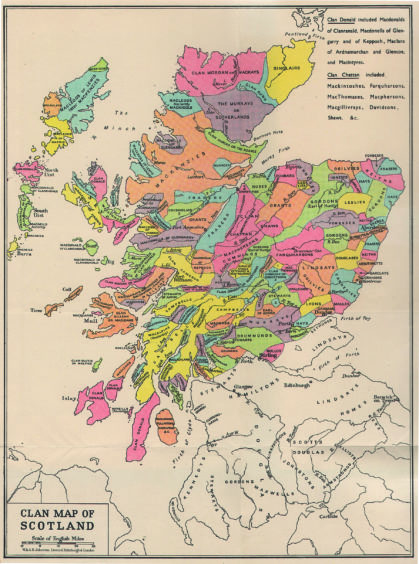

A detailed map in Vixy’s book shows that Courier Country was home to several clans including the Murrays, the Lyons, the Hays, the Moncrieffs and the Stewarts.

“We have quite a few of the of the aforementioned names as customers at Stewart Christie & Co,” she reveals. “The bloodline families still have a very real sense of instilled pride and respect for their family’s cloth. I have worked and created a number of pieces which were for the wives of the clan chiefs – they have some stylish ideas when it comes to using their tartan and it is far beyond a simple sash.”

Like any fashion, says Vixy, tartan ebbs and flows: “Sir Walter Scott’s 1822 Pageant, then Queen Victoria’s love affair with Scotland, 70s punk, 80s catwalks with Jean Paul Gautier amongst others, the 90s with Alexander McQueen.

“They are all noted by the dramatic or flamboyant nature of the cloth and it’s hard not to feel slightly patriotic or like you are making a statement if you use it in a garment or if you wear it yourself.

“I found it hard in my youth to want to wear it. Most teens want to blend into the background and be part of the pack, rather than stand out, and I guess tartan makes a statement, without you even having to say a word. When I use it, it tends to play with the geometry of it to create more dramatic lines and define form rather than be at odds with it.”

So does Vixy have a favourite tartan?

“I have been lucky enough to create the Stewart Christie tri-centennial tartan, and the weathered version is the first bolt to be produced, so making a tartan in this instance meant I was able to use more ‘tweed-like’ hues and tones,” she reveals.

“But my other favourite has to be the Ogilvy or Buchanan tartan. These are both some of the most colourful and complex tartans to have ever been woven. The sheer amount of colours in its history would have meant it was one of the most revered tartans, and it makes it hard to say if the current sett (pattern) design is the true and faithful recreation of what the original clan might have worn. It is colourful and complicated and has to be the king of colour palette, using between six and eight colours though many of its variants.”

And Vixy is confident that the future of tartan is as safe as its past.

“In the next fifty years I am sure the weaving techniques and the design of garments will be enchanted and refined, there may be changes in construction and colour but tartan will always have its romance, its myths and hark back to another age.”

The Secret Life of Tartan: How a Cloth Shaped a Nation by Vixy Rae is published by Black & White, £25.