It was a step into the unknown which nearly ended Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s literary career before it had even started.

Yet, although the creator of Sherlock Holmes admitted there were several occasions when he was close to a watery grave after joining the Peterhead whaling ship “Hope”, which sailed into the Arctic in 1880, he was also inspired by his experiences to begin drafting the back story of the famous Baker Street detective.

Jon Lellenberg, the co-author – with Daniel Stashower – of Dangerous Work: Diary of an Arctic Adventure, has investigated the remarkable story of how the young medical student embarked on a nerve-shredding journey, alongside north-east skipper John Gray and a crew of Peterhead and Shetland men, who braved sub-zero temperatures, and hazardous working conditions in one of the most remote places in the world.

One of Doyle’s classmates had gained the ship’s-surgeon berth on the Hope, but when personal reasons prevented him from going, Conan Doyle leapt at the opportunity — even though, to economise, he had striven to compress five years of study into four, and joining the voyage meant postponing his graduation from Edinburgh University.

Strong Bohemian element

There was no reason for him to leave his studies behind, especially given the risks involved, but once he and his colleagues departed Lerwick for the Arctic seas, he told his mother: “You will be glad to hear that I never was more happy in my life. I have got a strong Bohemian element in me, I’m afraid, and the life just seems to suit me.”

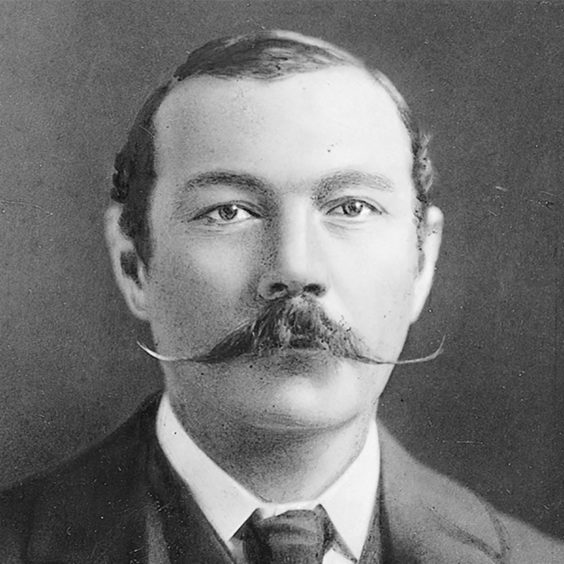

The words summed up Conan Doyle, a man of prolific talents: writer, surgeon, all-round sportsman, politician, criminal investigator, social affairs campaigner, the friend of Oscar Wilde and Harry Houdini, and, later in life, a believer in spiritualism.

He was a fellow who took mishaps in his stride and was determined to go out with the crew sealing on the ice, and later hunting whales by longboat. But that steely quest for adventure and resolve to be an active member of the crew often put him in jeopardy.

Mr Lellenberg told us: “One time, he came close to death from the frigid Arctic water, and recorded in his diary: ‘I had just killed a seal on a large piece [of ice] when I fell over the side.

“Nobody was near and the water was deadly cold. I had to hold on to the edge of the ice to prevent my sinking, but it was too smooth and slippery to climb up by, until at last I got hold of the seal’s hind flippers and managed to pull myself up by them.’

“He did not intend to stay aboard ship when others didn’t. In fact, he volunteered to participate in the hunt on the very first day.

“However, as he prepared to step into a boat, Captain Gray ordered him back — the ice was too dangerous for a novice. Annoyed at this, Conan Doyle sat down on an icy bulwark – and promptly fell overboard.

The Great Northern Diver

“He recalled: ‘The accident brought about what I had wished, for the captain remarked that, as I was bound to fall into the ocean in any case, I might just as well be on the ice as on the ship.’

“In fact, Conan Doyle fell in twice more and finished the day in bed while his clothes dried out in the engine room. He admitted later: ‘I had to answer to the name of the great northern diver [a seabird] for a long time thereafter.”

The youngster benefited from being an officer of the ship, as its surgeon, and was entitled to more private (if still spartan) living quarters than those of the ordinary crewmen. As he told his mother from Lerwick in April: “We carry capital champagne and every wine on board and we feed like prize pigs. I haven’t known what it was to eat with an appetite for a long time. I want some more exercise, that’s what I want.”

The crew was about two to one Peterhead men to Shetland islanders, and Conan Doyle seems to have harboured initial reservations about the latter after the Hope had completed the first part of its expedition from the Blue Toon to Lerwick.

He wrote in April, 1880: “Some of our hands work very well, while others, mostly Shetlanders with many honourable exceptions, shirk their work detestably. It shows what a man is made of, this work, as we are often killing far from the ship and away from the captain’s eye with a couple of miles drag, and a man can skulk if he will.”

However, by the end of voyage in August, he had amended his views and stated: “Our Shetland crew were landed [back at Lerwick] in four of our boats and gave three cheers for the old ship as they pushed off, which were returned by the men left.”

Return voyage offered

Mr Lellenberg added: “He respected and admired Captain Gray greatly, then and later, and said in his autobiography: ‘I see him now, his ruddy face, his grizzled hair and beard, his very light blue eyes always looking into far spaces, and his erect muscular figure. Taciturn, sardonic, stern on occasion, but always a good just man at bottom – he was a really splendid man, a grand seaman and a serious-minded Scot.’

“The captain, for his part, came to respect and admire the young surgeon and, at the end of the voyage, he invited Conan Doyle to return for the next year’s [trip], as a harpooner as well as surgeon. (‘It is well that I refused,’ the author subsequently reminisced, ‘for the life is dangerously fascinating.’)

“In Peterhead, the captain’s home is now the Clifton House Hotel, where Conan Doyle stayed a few days in February 1880, and my wife and I were there in 2012.”

Despite being a prodigious diarist and writer with a vivid imagination, it would be several years before he brought Holmes and Watson to life. But, as Mr Lellenberg explained, the seeds were already being sown for the development of the character who has become widely regarded as the greatest detective in literary fiction.

He said: “It occurred in the next-to-last entry in Conan Doyle’s diary, August 10, 1880, as the Hope returned to Scotland. They stopped at Lerwick to let the Shetlanders off, and he wrote: “The lighthouse keeper came off with last week’s weekly Scotsman by which we learned of the defeat in Afghanistan. Terrible news.’

“I could barely believe my eyes when I read. The report on July 29 was headed: ‘Disaster in Afghanistan/Severe Defeat of Burrows’ Brigade/ Retreat on Kandahar.’

‘[It told of how] a British force of some 3,000 [troops] had been nearly annihilated at Maiwand by Pathan tribesmen.’

“Six years later, in medical practice in Southsea in Portsmouth, [Arthur] began writing a detective story narrated by a British Army doctor seriously wounded at that Battle of Maiwand, the name of which he had recorded in his Arctic diary — Dr John H Watson!

“[After] returning to London, uncertain about his future, and looking to share the expense of lodgings with someone, Watson is introduced to a man described as ‘a little queer in his ideas – an enthusiast in some branches of science.’

“How are you?” says the peculiar man whom Watson meets in the laboratory of St Bartholomew’s Hospital: ‘You have been in Afghanistan, I perceive.’

“This was [the original entrance of] Sherlock Holmes, thus beginning the fictional partnership that brought Conan Doyle literary fame and fortune.

“Nobody had previously had any idea that a vital seed for A Study in Scarlet, the first Sherlock Holmes tale, had been planted in the Arctic voyage of Conan Doyle, until my collaborator Daniel Stashower and I read this long-buried diary for our book.

“We were both pretty excited.”

The impact of the trip on Arthur Conan Doyle’s literary career

After returning from his action-packed foray into the far North, Conan Doyle began to write about the Arctic, in his new side-career as an author soon after arriving in Southsea in 1882.

An eerie short story, “The Captain of the ‘Pole-Star’,” which appeared in the January 1883 issue of Temple Bar, was based on the sights and experiences aboard the Hope.

Consider this extract. “Look here, it’s a dangerous place this, even at its best—a treacherous place. I have known men cut off very suddenly in a land like this. A slip would do it sometimes—a single slip, and down you go through a crack, and there’s only a bubble on the green water to show where it was that you sank.”

That year, Conan Doyle joined the Portsmouth Literary & Scientific Society and, in December, gave a talk on “The Arctic Seas” which established him with the town’s intelligentsia. Its main thrust was the quest to reach the North Pole, and what he believed to be the right way to do it. “The lecture is over – and was an unqualified and splendid success,” he reported to his mother.

In the future, he would return to the subject of the Arctic and whaling ships a number of times: in an essay entitled “The Glamour of the Arctic” in The Idler of July 1892, which led to a lifelong friendship with the Norwegian explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson; and during a personal account of his voyage aboard the Hope entitled “Life on a Greenland Whaler” in the January 1897 Strand Magazine.

Bringing us back to Baker Street was the 1904 Sherlock Holmes story “The Adventure of Black Peter” in which the captain of a whaler is found “pinned like a beetle on a card” by a harpoon thrust through his chest. The initial efforts to track the killer are hampered by the bunglings of the police, but Holmes, as usual, rises to the challenge.

Then, in a 1910 address to a London luncheon in honour of North Pole explorer Robert Peary, Conan Doyle regretted that the “blank spaces” on the world’s map were being filled up by “the ill-directed energy of our guest and other gentlemen of similar tendencies”; and, in his 1924 autobiography, Memories and Adventures, he devoted an entire chapter to his voyage aboard the Hope.

Ten surprising things about Arthur Conan Doyle and Sherlock Holmes

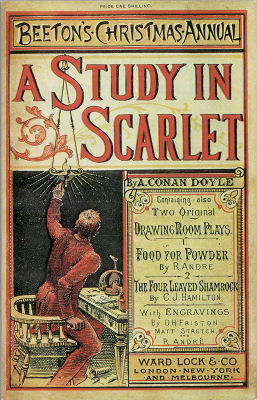

- Doyle initially struggled to find a publisher for his maiden Sherlock Holmes book. A Study in Scarlet was written in three weeks when he was 27 and purchased by Ward Lock & Co in 1886 for the less-than-princely sum of £25.

- He was a keen cricketer who played 10 first-class matches for the MCC. While he took just one first-class wicket, it was the prized scalp of the legendary W G Grace.

- He was also an accomplished amateur boxer and, in 1909, was invited to referee the James Jeffries v Jack Johnson heavyweight championship fight in Reno, Nevada. Doyle wrote: “I was much inclined to accept…though my friends pictured me as winding up with a revolver at one ear and a razor at the other. However, the distance and my engagements presented a final bar.”

- 4. Sherlock Holmes is one of the few fictional characters to have their own tartan. It was created two years ago by north-east woman, Tania Henzell, who said: “It has been well received, especially by the Americans and Japanese and I hope to be selling the tartan in Switzerland at the Meiringen Museum, which is near the Reichenbach Falls where Holmes and Moriarty met.”

- 5. He stood for Parliament twice as a Liberal Unionist – in 1900 in Edinburgh Central and in 1906 in the Hawick Burghs – but although he received a respectable vote in both instances, he was not elected.

- 6. Doyle was a fervent advocate of justice and personally investigated two closed cases, which led to two men being exonerated of the crimes of which they had been accused. The most famous case, in 1906, involved a shy half-British, half-Indian lawyer named George Edalji who had allegedly penned threatening letters and mutilated animals in Great Wyrley. This was turned into a TV drama series, starring Martin Clunes, Charles Edwards and Art Malik in 2015

- 7. He was a remarkably prolific writer. In addition to the Holmes canon, his works include fantasy and science fiction novels about Professor Challenger and humorous stories about the Napoleonic soldier Brigadier Gerard, as well as plays, romances, poetry, non-fiction and historical novels. One of his early short stories, “J Habakuk Jephson’s Statement” helped to popularise the mystery of the Mary Celeste.

- 8. He was a fervent believer in spiritualism, especially in the wake of the carnage which occurred during the First World War. “The New Revelation” was the title of his first major Spiritualist work, published in 1918, and he frequently attended seances.

- 9. In 1914, on a family trip to the Jasper National Park in Canada, he designed a golf course and ancillary buildings for a hotel. The plans were realised in full, but neither the golf course nor the buildings have survived.

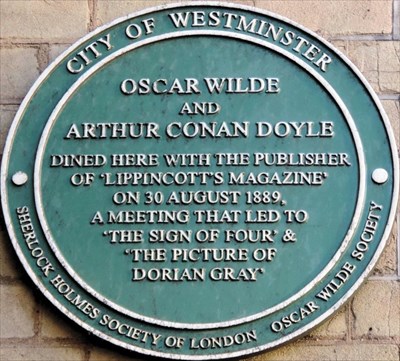

- 10. While enjoying an evening together at the Langham Hotel in London, an American editor asked Doyle and Oscar Wilde to write new novels to be published in his magazine. It was an invitation which led to the creation of The Sign of Four by Doyle and the Picture of Dorian Gray by Wilde.