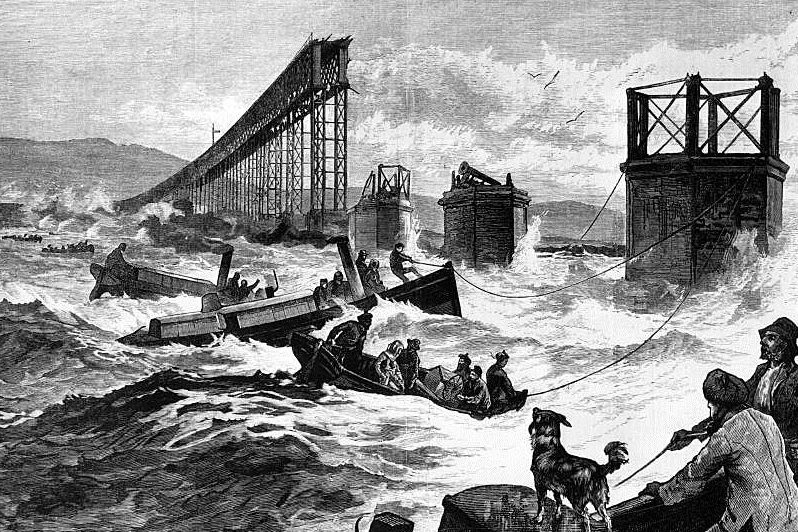

Divers were still searching for bodies amongst the broken stumps of the first Tay Rail Bridge when the first underwater communication in Britain took place 140 years ago.

The Telephone Company Ltd arrived in Dundee to open an exchange in the city at the time divers were working in the River Tay.

They were crawling through the debris, wearing more than 40lb of lead weight, along with a stifling airtight helmet that was connected to the surface by an air pipe and communication line.

The part of the Tay where the train sunk on the night of December 28 1879, was known for its strong tides and ever-changing sands.

Earl Grey Dock link

The Telephone Company Ltd immediately offered a service to link the divers on the salvage barge to people on the shore.

The locomotive driver David Mitchell had just been found washed up on a nearby beach nine weeks after the tragedy when a telephone wire was linked to the earpiece of a diver in Earl Grey Dock and the shore.

The underwater link was still in place a few weeks later when the engine which led its doomed train on to the Tay Bridge in 1879 was eventually brought to the surface.

Of the 46 bodies which were eventually recovered, at least 59 are known to have died, and it is thought the death toll could be as high as 75.

Despite the endless hours they spent in the icy water, only three of the recovered bodies were brought out by divers.

The Telephone Company Ltd also installed a line between the then Dundee Central Station, the exchange at India Buildings, and the city museum, and invited the public to try it out for themselves.

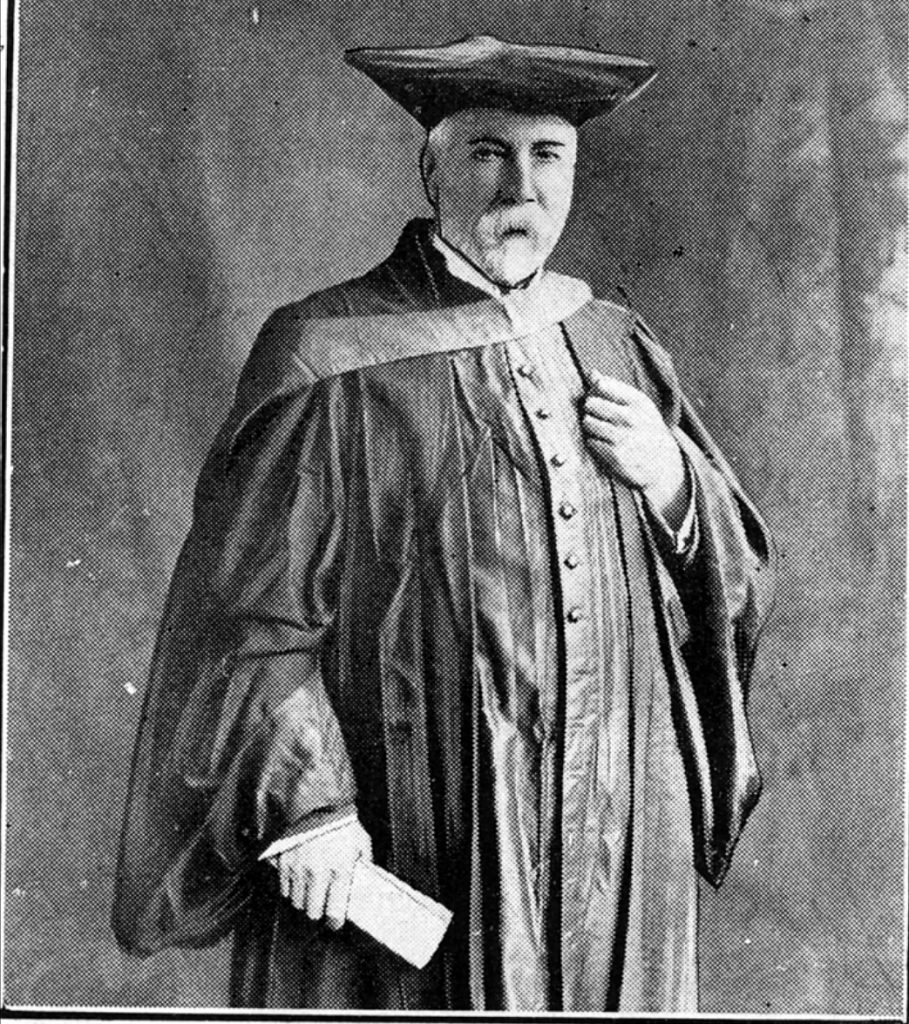

The first person to have a telephone in Dundee in 1880 was James Caird who had a merchant’s office in Cowgate.

Caird’s money was made through Dundee’s staple industry, jute.

He was one of Dundee’s most successful entrepreneurs who went on to donate substantial sums to extend the Dundee Royal Infirmary and gifted both the Caird Hall and Caird Park to the city.

First telephones in Newport

He had a private phone line installed between his office, his home in Magdalen Green, and his factory in Hawkhill.

The Dundee exchange was one of the first in Britain after opening just four years after the first telephone call was made by the Scottish inventor of the telephone, Alexander Graham Bell.

Bell’s initial idea was not to invent the telephone but to achieve a means of communication for the deaf.

The first telephones then arrived in Newport in 1882 when a cable was laid over the new Tay Bridge which was being constructed exactly parallel alongside the old.

There were four subscribers in Newport who could call each other via the operator in Dundee.

Before the invention of automatic telephone exchanges, the assistance of a telephone operator was required to connect the two telephone lines.

Submarine cable

The caller would speak to an operator at the central telephone exchange, who would connect a cord to the correct circuit in order to complete the call.

The first submarine cable was then laid across the Tay in October 1883 which allowed much improved communication and ran from near the Stannergate in Dundee to a point west of the Tayport lighthouses.

In 1885 the Lord Provost of Dundee telephoned the Lord Provost of Perth.

It is recorded that he whistled a verse of Auld Lang Syne as his way of signalling the introduction of the trunk call service to Perth.

Then there were three subscribers in Perth: Pullar’s Dye Works, the Caledonian Railway and a Mr Sime.

By 1912, there were seven separate private phone companies operating throughout Britain.

A speaking clock service was first introduced in Britain in 1936 which gave Dundee another communication ‘first’ some 80 years later.

Pride at becoming the fifth voice

Alan Steadman, from Broughty Ferry, became the first non-English voice of the Speaking Clock, and he said he was proud to be part of Dundee’s telecommunications legacy.

Mr Steadman said: “It’s amazing to learn about the major role that Dundee played in the development of telecommunications as far back as the time of the Tay Bridge disaster.

“I had no idea that those brave divers were the first to embrace underwater technology.

“It certainly adds to the pride that I have felt since becoming the fifth voice of the BT Clock – and the first Scottish one – back in 2016.

“Since then, as a result of that, many interesting things have happened.

“At the risk of blowing my own trumpet, I have been the subject of questions on a number of TV quiz shows including Mastermind, The Chase and 15-to-1.

“I have featured in a number of magazines, the most prestigious being Esquire, and I have even appeared on TV alongside Ant and Dec!”

Mr Steadman said he regards the Speaking Clock as an archetypal British institution.

He said: “Some say it was the first phone call they ever made.

“Although things have changed with the development of the internet and mobile phones – and will no doubt continue to do so – it is interesting to note that the service is still used to the tune of 700,000 calls per month with peak times on New Year’s Eve, Remembrance Sunday and when the clocks change.

“It seems therefore that some traditions never die and let’s hope that this particular one goes on for some time to come.”

Around eight in 10 UK households (81%) have a landline service, but the volume of mobile calls in the UK has increased steadily in recent years, from 132.1 billion minutes in 2012 to 151.4 billion in 2017, while landline call volumes nearly halved in the same period, falling from 103.1 billion minutes to 53.6 billion.

Despite this decline, many people still depend on their landline, such as those who do not own a mobile phone.

Jute king was first person with phone

The first person to have a telephone in Dundee was born in a mansion in Perth Road on January 7 in 1837.

James Key Caird took control of the family textile business, Caird (Dundee) Ltd, after his father, Edward, retired.

Harnessing the latest mechanical improvements, he expanded the business aggressively and extensively, and profits grew exponentially.

At the same time, his Ashton and Craigie Jute Works in Hawkhill became a model of comfort for the working class men, women and children harboured there.

In July, 1873, he married Margaret Gray, the daughter of a Perth banker and sister of Effie Gray, the wife of the famous painter Sir John Everett Millais.

But Margaret died, leaving a daughter Ada, who died young.

He made a substantial fortune from his business interests and reinvested much of it in his home city.

Local patriotism

He was knighted by King George V in 1913, by which time he was considered a good employer and was firmly involved in the impetus for civic improvement in Dundee.

His local patriotism is witnessed by the Caird Hall in the centre of the city, for which he donated the huge sum of £100,000 in 1914.

Sir James also purchased the ground which became Caird Park for £25,000 as a gift to the city, thereby doubling Dundee’s leisure ground in a single gesture.

Other bequests during his lifetime included £8,000 for a women’s hospital in 1897, £24,000 for a cancer hospital at DRI in 1902, £10,000 for the Sidlaw Sanatorium, Auchterhouse, in 1905, £5,000 for the Caird Rest Home in 1911, £5,000 for the Royal Society in 1913 and £12,000 for the Prince of Wales’ Relief Fund in 1914, the year he funded Ernest Shackleton’s expedition Antarctic expedition.

Following the death of Sir James in 1916, a sum of £100,000 was placed in the Sir James Caird Land Acquisition Fund, and its money was used to buy Camperdown Park for the city and other properties around its boundaries.

A further £20,000 was made available to set up Sir James Caird’s Travelling Scholarships in engineering, electricity, aeronautics and music.

The Marryat Hall, which links to the Caird Hall, was subsequently gifted to the city by Sir James’s sister, Emma Grace Marryat.