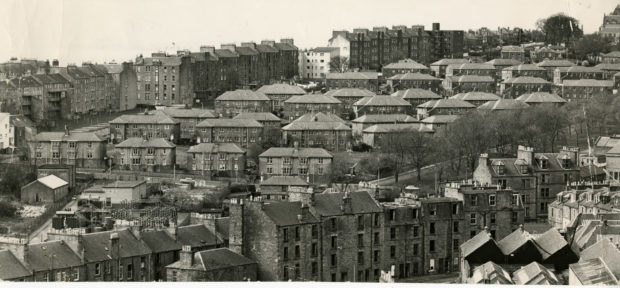

They were the ‘little castles’ which put Dundee on the housing map at home and abroad.

‘Logie Day’ marked the coming of the change from the dingy streets crammed with sombre houses to the open spaces with greenery and flowers.

Renowned city architect

Logie estate’s four-flat blocks, designed by renowned city architect James Thomson and centred on a tree-lined avenue, was a model that imitated upmarket villas and which departed from high-rise tenements.

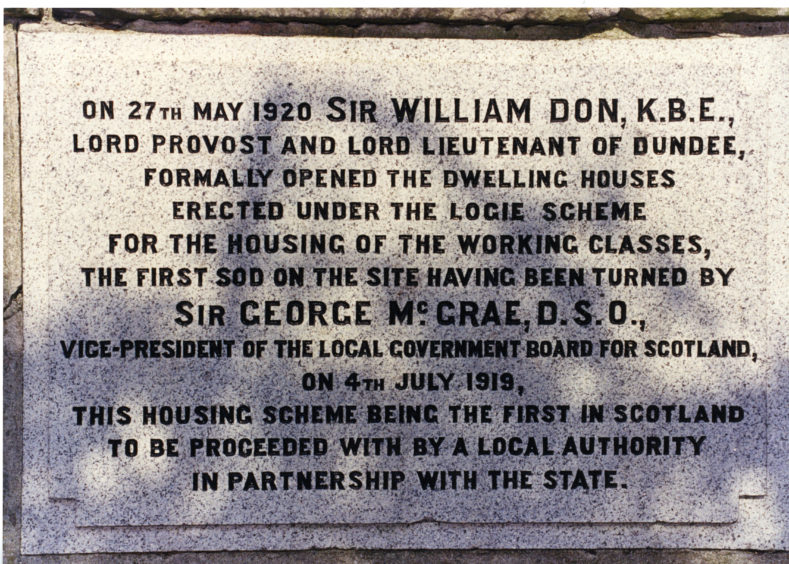

It became Scotland’s first council housing scheme and the first estate in Europe to have a district heating system when it was opened 100 years ago today by Lord Provost Sir William Don.

The coal boiler house that supplied the residential development also provided a public wash-house for the surrounding area.

The ‘homes for heroes’ cost £230 each to build and the rent for a two-room house was one shilling and three pence.

For a three-room home, it was one shilling and nine pence.

At this time there were 90 houses finished and ready to become homes.

Superior in many respects

Sir William opened one of the houses with a gold key which was presented by Mr Thomson while Dundee’s Black Watch military band played.

He said the city had been taking measures to ensure its existing houses were in a habitable condition and many slum properties as a result had been closed.

He said the Logie houses were little castles, superior in many respects, and equipped in a manner which was ahead of many of the larger and more highly-rented houses.

Sir William said it was a veritable garden city – neat little houses and a little garden plot outside – and at the same time in close proximity to the city, and convenient for working people.

He said the founding of such a scheme necessarily departed from the path of political economy, but the call upon the government, and upon local authorities, had been so strong that it must be answered.

“The people must have houses to live in,” he said.

“In particular the men who have fought and risked their lives on behalf of their country must be provided with comfortable homes and a decent chance of bettering their condition.

“The town council has therefore stipulated that in the first place ex-servicemen should have the first call upon the houses.”

Preference was to be given to ex-servicemen who were married, or the widows of ex-servicemen, or ex-servicemen who were to be married.

Special consideration was to be given for men who joined the war at the outbreak in 1914.

Slum conditions

Sir William said he believed that the whole of the Logie houses would be allocated to demobilised ex-servicemen.

He made particular reference to the hydro-electrical scheme for Scotland.

He said he looked on this as being of equal importance as housing.

In 1905 Dundee Social Union had carried out an innovative study of housing conditions in Dundee’s slum city centre.

Inspectors visited more than 6,000 properties and discovered housing conditions were appalling and accounted for a huge range of diseases and, probably, high levels of child mortality.

They concluded that housing was the greatest social evil.

The new homes were necessary to address its dreadful housing, described by the 1917 Royal Commission as ‘32,000 living in overcrowded conditions in Dundee’.

The end of the First World War in 1918 created a huge demand for working class housing in towns throughout Britain.

The 1919 Act – often known as the Addison Act after its author, Dr Christopher Addison, the Minister of Health – made housing a national responsibility.

Local authorities were given the task of developing new housing and rented accommodation where it was needed by working people.

‘Civilised life could not be observed’

John Reid, convener of the housing committee, said it was the first milestone on the way to greater municipal efforts.

He made reference to the “unhealthy system of back lands, the barrack square system, with the reservoir of bad air and unhealthy sanitary conveniences, the overcrowded areas where from 400 to 600 persons were living to each acre, and the large number of decencies of civilised life could not be observed”.

The expected rate of occupancy of Logie was 54 persons per acre.

He said the future held much promise and was also pregnant with difficulties.

The Lord Provost afterwards unveiled a memorial tablet on the viewpoint and under the direction of the clerk of works, the public had a chance of inspecting the housing.

The jobs of the first tenants at Logie included artist, railway clerk, telegraphist, soldier, jewellery salesman and commercial traveller.

The estate has survived to this day relatively unaltered although a large number of the properties have been sold off and are no longer under council housing stock.

Logie remains a triumph

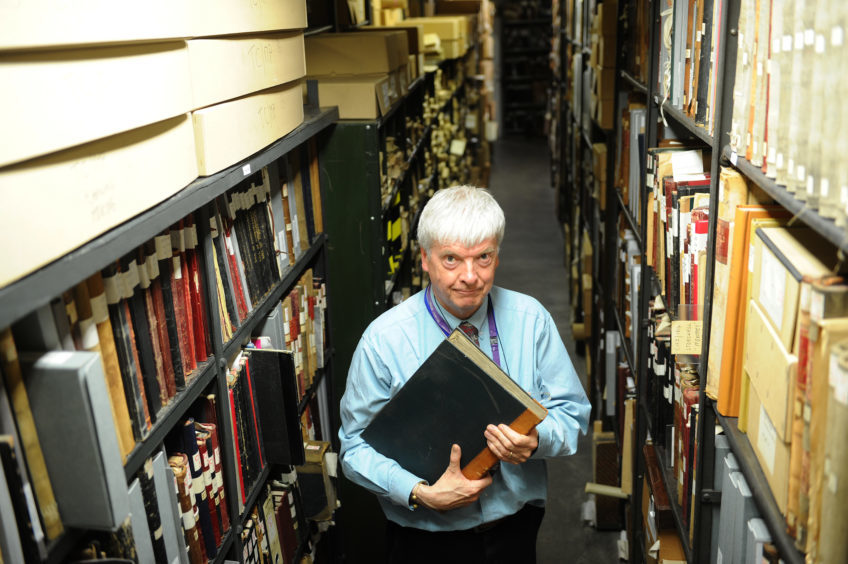

Iain Flett from the Friends of Dundee City Archives said: “The Logie Housing Estate was and remains a triumph.

“Planned in the days of slaughter of the Great War by the genius city architect James Thomson, one of the creative town planners of his day, who also designed the Caird Hall and the ring road, it was the first public (council) estate to be built in Scotland, despite the trials of scarcity of both manpower and materials in the post war shortage.

“The Logie maisonettes had their own inside bathrooms, a source of envy in a city where many would queue in municipal wash-houses for a weekly bath, and were heated by a district heating scheme centred at Scott Street.

“Although replaced in the 1970s, this was a concept a hundred years ahead of its time.

“The Scottish Government, in its efforts to reduce global warming, is now encouraging modern district heating schemes such as the Slateford Green community heating scheme in Edinburgh, which hosts 120 domestic connections, and four tower blocks in Stockethill, Aberdeen, with a community heating system hosting 262 domestic connections.”

Council housing boom

In the period between the First and Second World Wars, around 11,000 council houses were built in Dundee, using a diverse range of materials, including concrete, brick, wood and even metal from melted-down aeroplanes for prefabs.

In Dundee, 180 council houses of the Taybank scheme were completed in 1924, and 280 at Craigie by 1928.

Quickly, Dundee had one of the highest proportions of council tenants in Britain.

By the end of the Second World War, decentralisation of industry legislation changed the city’s industrial landscape.

As firms like NCR, Timex, Astral, Burndept and Holo-Krome transformed the manufacturing sector, so urban renewal was accelerated by people wishing to live nearer to the peripheral factory sites.

Model estates like the 3,000 homes built at Fintry between 1949 and 1960, and the 1,200 homes at Charleston were created.

People moved in droves from the decaying heart of the city to the brave new world of electronics on the boundary.

Come the 1960s multi-storey blocks seemed to be the answer to evolving housing demand.

Dundee led the way in January 1960 when the 10-storey Dryburgh block rose.

By 1980, there were 55 multi-storey blocks in the city, providing 5,087 homes and housing a population equivalent to a town the size of Forfar.

By then, however, there was also a realisation that decanting from slums did not necessarily mean solving social problems.

Peoples’ aspirations also changed and clearance of unwanted homes – officially known as twilight areas – began in the early 1990s.

In recent years the demolishers hammer has also swung at Trottick, Mid Craigie, Whitfield, Beechwood, Kirkton and Ardler.