It was the River Tay tragedy where 17 churchgoers lost their lives and 15 children were orphaned.

The Tay Ferry Disaster in 1815 ultimately transformed safety regulations on the crossings where “drunkenness and disorder prevailed”.

A meeting was held in the Exchange Coffee Room in Dundee 205 years ago in June 1815 in the wake of the catastrophe.

Only seven were saved

The accident some days earlier on May 28 happened about half-a-mile from Newport when the Pinnace passenger vessel was overwhelmed by a sudden storm and only seven of the 24 people on board the Sunday service were saved.

Hugh Scott and his younger brother were among those saved by swimming and pulling themselves up to a sailing craft which the ill-fated ferry had been towing during its doomed journey.

A boat from Newport came out and attempted to rescue the remaining passengers from the water without success.

They were only able to pick up those on the sailing craft and took them back to the village.

The news spread rapidly throughout Newport and there was a general rush to the Craig Pier to learn about the disaster.

The churches in Dundee were almost deserted that forenoon.

In the aftermath of the disaster there was conflicting evidence and rumour about the “barbarous indifference” of the crew of another ferry when the boat capsized.

At that time different ferry companies were competing for business on the River Tay.

Little hope

At the meeting in the Exchange Coffee Room, resolutions were passed inside those walls which drew attention to the fact that the poorly equipped service was in need of being “improved in its future regulation and management”.

It was resolved to take action in conjunction with the freeholders of the two counties of Fife and Forfar, with the view of inquiring into the state of the ferries, to ascertain if some improvement could not be adopted in their management.

The result was that a Joint Committee of Inquiry was appointed, and a “searching investigation was made into the whole subject”.

Little hope

The passengers who perished were on their way to hear the farewell sermon of Mr Chalmers of Kilmany.

Most of those who died left behind helpless widows, or children, or brothers and sisters, or parents.

For orphaned children in Dundee at that time there was little hope other than life on the streets or a bed in the poorhouse.

But things were slowly changing.

Local businessmen were spurred into action which worked to the advantage of the newly-formed Dundee Society for Educating Orphans, Fatherless Children and the Children of the Industrious Poor.

The desperate need within the city had already been recognised on February 9 1815, when four local gentlemen first met in the Baker’s Room of the Trades Hall to discuss the opening of an orphanage.

The aims of the society were to assist the more helpless and destitute of the community – orphans and fatherless children – while striving to educate children whose parents worked in Dundee’s textile mills, shipyards and whaling industry.

Donations poured in to the society following the tragedy.

The sum of £700 was raised and a property in the city’s Paradise Road was rented.

Nine boys and 12 girls became the first residents of Dundee Orphan Institution which was staffed by a matron and two teachers.

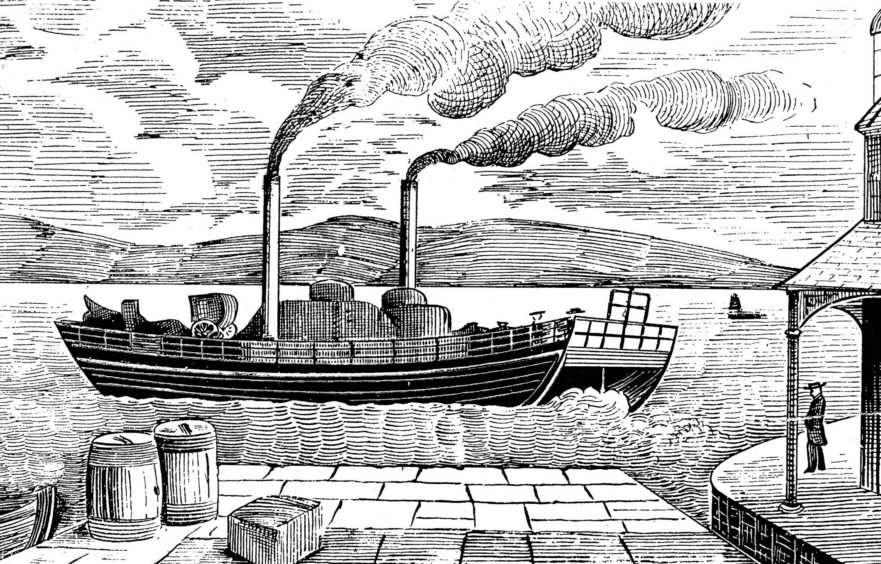

The ferry service was eventually regulated under the Tay Ferries Act and in 1821 a steam twin-hulled paddle boat called the ‘Union’ was put into service and ran from Dundee to Newport.

At first services had also run to Woodhaven but it eventually proved too difficult to keep two different routes.

Captain Basil Hall

Captain Basil Hall, who served in the navy for 21 years, is the best known source with regards the aftermath of the tragedy.

Hall served aboard many vessels involved in exploration and scientific and diplomatic missions.

From the beginning of his naval career he had been encouraged by his father to keep a journal, which later became the source for a series of books and publications describing his travels.

In his writings he clearly saw the disaster as transformational.

Captain Hall’s account of the Tay Ferry Disaster first appeared in the Edinburgh Philosophical Journal and was reprinted in the Dundee Advertiser in 1825.

He said: “There were at this time 25 boats on the passage, manned by upwards of one hundred men and boys.

“The boats were ill-adapted to the service required; the crews were composed of infirm old men, or equally inefficient boys; and as there was no system of management or any kind of discipline, much drunkenness and disorder prevailed.

“There being no regular superintendent to direct the sailing of the boats, the passengers, on reaching the landing-place, had either to hire a whole boat, at a great expense, or to wait till a sufficient number of persons had assembled to make up the fare.

“This was productive of great hardship to the poor, and inconvenience to all parties; and, added to the discomfort of bad landing-places and unskillful management, rendered the simple passage of a mile and a half, especially in blowing or rainy weather, a service of no small risk.

“In 1817, the Counties of Fife and Forfar appointed a Joint Committee, to consider the state of the ferry, and to concert measures for its improvement; and it being apparent, upon a slight examination, that, in spite of all its drawbacks, the ferry produced a revenue adequate, with proper care, to the maintenance of a far better system, the number of boats was reduced from 25 to eight, and at the same time rendered efficient by stronger crews, better equipment, and, as far as was possible, by punctuality of sailing at stated periods.”

Captain Hall said that although the reduction of the number of boats was considered expedient in 1817, the arrangement was not carried into effect until 1819; when the ferry was vested in the Trustees, by the first act of parliament.

In 1973 the society reprinted "An Account of the Ferry Across the #Tay at #Dundee" written by Captain Basil Hall in 1825 – you can read it for free here https://t.co/xq7u809wxk

— Abertay Historical Society (@AbertayHS) April 12, 2020

In 1819, an act of parliament was procured for erecting piers, and otherwise improving and regulating the ferry across the Tay.

River Mersey

During the discussions on this bill, the idea of employing steamboats first suggested itself to the Trustees; and, after careful inquiries, they decided upon trying the experiment with a double or twin steam vessel.

They found out these vessels had already been in use for some years on the American rivers, and also at Hamburg, and on the River Mersey, near Liverpool.

#ChrisBeetlesSummerShow is officially open! A particular highlight from this year's exhibition of superlative #British & #American paintings & sculpture includes 'The First Steam Boat on the Mersey – Sunset, Liverpool Beyond' by Leonard Campbell Taylor RA: https://t.co/XW6ZTURTpN pic.twitter.com/x2sTvuJzDy

— ChrisBeetles Gallery (@CBeetlesGallery) May 30, 2019

It was not, however, till towards the end of the year 1821, that the steamboat began to ply across the River Tay.

Local historian Dr Kenneth Baxter from the University of Dundee said the 1815 disaster was a key event in the history of the Tay Ferries for it led to regulation and ultimately regularly scheduled sailings on a small number of dedicated boats.

He said: “I think it is fair to say that the disaster, combined with the coming of steam ferries (starting with Union in 1821) and the decision to adopt the Dundee-Newport (rather than Dundee-Woodhaven) route in the 1820s laid the ground work for the system that survived until the opening of the Tay Road Bridge in 1966.

“The various ‘Fifies’ that served on this route were very much a part of Dundee life until their final crossing.

“It is interesting that the disaster is not better known today.

“One possible explanation is that the loss of life was completely eclipsed 64 years later when the Tay Bridge Disaster occurred.”

Carolina House Trust, the successor of Dundee Orphan Institution, is still doing great work for the city’s children 205 years after the disaster.