Two time capsules – buried for centuries – remain etched into the very fabric of Brechin Cathedral and its Round Tower.

A time capsule was embedded in the foundations of the Round Tower during an exploratory investigation in 1842 and remains there to this day.

Dark Ages

There is also a time capsule which was embedded in the chancel during the restoration of 1900-02.

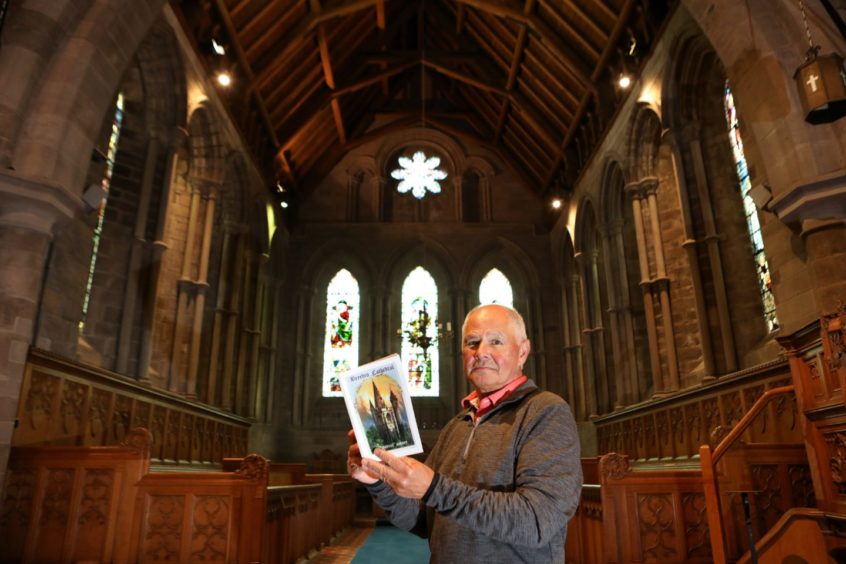

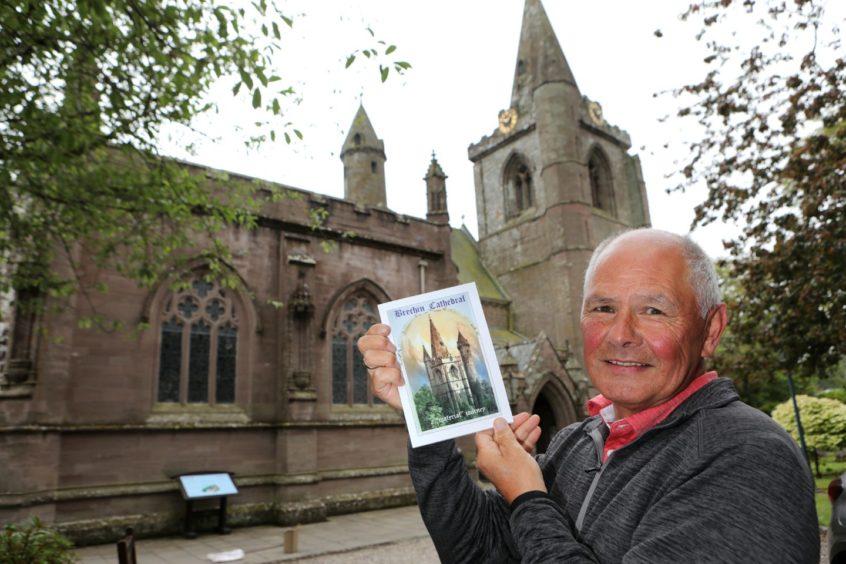

A new book is exploring the history of one of Scotland’s oldest places of worship from the Dark Ages through to its imminent closure after 800 years.

The church survived attacks from King Edward I who stripped the roof of its lead in 1303; invasion by Montrose’s royalist forces where half of the town was set on fire; and Oliver Cromwell’s onslaught in 1650.

But it couldn’t survive bankruptcy after being left saddling huge debts following a botched roof repair after dry rot was found in the Canadian pine timbers.

On a small notice as you enter the Cathedral are the words:

“This Cathedral has stood here for more than seven hundred years.

“In this place God has been worshipped and our forefathers have confessed the Faith of Jesus Christ.

“As you enjoy this hallowed building remember that you are standing on holy ground, and think not to leave this House of God without lifting up your heart in thanksgiving and prayer.”

Church elder Archie Milne has now embarked on a “material journey” going back through time before the church is put on the market.

“There would have been a religious settlement on the present site of the Cathedral and more and likely this would have been the Druids from around 600AD,” he said.

“Our history of the cathedral more or less starts around 975AD with King Kenneth II of Scotland granting powers to the burgh of Brechin as he ‘gave the great city of Brechin to the Lord’ thus bestowing special privileges.

“The church at Brechin received a significant royal grant, probably of lands, and it was this which gave the church the power to create a burgh and hold markets.

“This then leads through to King David who installs Bishop Samson to the church and thereby making it a cathedral.

“This history goes on with respect to the building of the actual church, its new foundations in 1220AD, the building of the Square Tower and the grant given by Robert The Bruce.”

Capture of Brechin Castle

The timber roof is modern but there is an old tradition that the original oak beams of the roof came from the forest of Kilgarie on the slopes of the Caterthuns on the fringe of the Angus Glens.

In 1303 when King Edward I attacked and captured Brechin Castle, the counterweights of his siege machines ‘War Wolf’ were made of lead stripped from the roof of the cathedral.

Two years later however he compensated Bishop Kyninmond for the value of the lead he had commandeered with a consignment of 50 loads of lead and gifted 12 oaks for timber from the forest of Forfar.

King Robert the Bruce later visited Brechin in 1310AD and gifted 100 merks which was approximately £65 for the ongoing construction of the Square Tower with the work lasting into the next century.

Brechin was occupied on five occasions by James Graham, 1st Marquis of Montrose, and the royalist troops of England.

The first time in 1644AD was short as the Marquis of Argyll and the Scottish army arrived and made the town a rendezvous for the horsemen and footmen.

A month later Montrose’s army again occupied Brechin and all the inhabitants fled into the country.

In 1645AD Montrose again occupied Brechin and during that time he plundered the town.

Mr Milne said: “Half of the town was set on fire and the terror-stricken people fled once again for refuge in the country.

“They hid their goods in the castle and the church steeples, which enraged the soldiers who found their goods, plundered the castle and half the town and burnt about 60 houses.

“After this Brechin was given a respite to restore things to normal.

“The town was in a heartbreaking state of upheaval and disorder.

“The church had been broken into and ransacked.

“The collection take on the Sunday just before Montrose’s arrival had been hidden in a secret part of the church but the enemy found it and stole it.

“The Church Bible had been attended to and was safe but one of the Session Registers was gone and never recovered.

“Once again, Montrose, with the largest army he had ever commanded, occupied Brechin for several weeks.

“The memory of what had happened four months before sent the people fleeing into the country again.

“This was not the last time that Brechin was to see Montrose as later that year his army spent almost a month outside of Brechin which kept the people in constant fear.”

Two years after the havoc brought by war, Brechin was once again plunged into horror by the onset of the plague.

Filth and refuse

The streets in the 1600s were the recognised refuse heaps of the community.

Here accumulated unheeded and undisturbed the filth and refuse of the neighbouring households.

From time to time in the church records, there are indications of payments to clean up the approaches to the church and the churchyard.

There were no services in the church after April 7 1647 and all Session meetings were discontinued for seven months.

The houses infected by the plague were closed and not reoccupied until the ‘cleansers’ had cleaned the rooms and furniture, and also boiled the foul clothes and bedding in cauldrons.

On September 3 1650, the English Parliamentarian army under the command of Oliver Cromwell defeated the royalist-supporting Scottish Covenanting army at the Battle of Dunbar.

The magistrates of Brechin were called upon to supply their quota of recruits.

The cathedral was used by these invading troops to shelter both the army and their horses.

The book also highlights Brechin’s association with the powers of darkness where women deemed to be witches were burned at the stake.

Marion Marnow was executed in 1619 and about 30 years later Jonat Coupar suffered the same fate after she was observed to kiss a dog one day while passing along the Brig of Brechin.

Last witch

Coupar claimed that she had known the Devil for around four years and her first meeting with him happened when she was on her way to the mill.

She is believed to have been the last witch burned at the stake in Brechin.

The room immediately above the Vestry at Brechin Cathedral is known as ‘the witches room’ and this is because women were held there prior to being taken to the stake.

The book also looks at many important artefacts such as the brass candelabra which hangs in the chancel and is known as a Hearse which is Flemish in design and dates from 1615.

For more than 300 years it hung in the nave before being moved to the chancel in 1950.

Towards the end of the 19th century, the congregation of Brechin Cathedral was unhappy with the results of the restoration which had been done some 50 years earlier.

This resulted in them deciding that further restoration was needed and the Glasgow firm of Honeyman and Keppie were contracted to redesign and build the church in keeping with ‘modern’ times.

A fund of £10,000 was needed for this restoration and, towards the completion in 1902, it was felt that the chancel should have some stained-glass windows.

“The cathedral has 39 stained glass windows and these emanate from the 1902 restoration,” said Mr Milne.

“The first 14 windows were installed by Henry Holiday who was a London artist while the balance was done by Scottish artists to a completion date of 1978.”

Holiday, a Londoner, was commissioned to design and install three windows, these portraying Jesus as prophet, priest and king.

When these windows were completed, he convinced the Session of the cathedral that he must be given the opportunity to complete the other 10 windows in the chancel and as such he designed them depicting the life of Jesus.

The windows are shown in full colour and detail the subject matter, giving references to both the artist and year of installation.

The artists included William Wilson, Douglas Strachan, Herbert Hendrie, Henry Dearle, Gordon Webster, Hugh Easton and David Gauld, who was one of the Glasgow Boys.

Gauld designed the windows at either side of the chancel while Strachan designed the war-memorial window as a tribute to the 14 members of the congregation who perished in the Second World War.

Wilson designed 16 of the 39 windows in the church, including the window dedicated to St Andrew.

Another of the Glasgow Boys was Charles Rennie Mackintosh who designed the new pulpit.

“There is a section on the Pictish monuments and the carved stones within the church,” said Mr Milne.

“These range from the Aldbar Stone through to the St Mary Stone, the Hogback and a variety of other stones specific to the Cathedral.

“These stones are typically 800 to 1,000 years old.

“There is also a section which deals with the collection of communion tokens which was made by Rev William Burns in 1964 who was the Minister of Stracathro Church.

“These tokens vary in age from 1775 through to 1918 and relate to churches from Angus and the Mearns.

“The history of each church is specific of that church at the time of its token and many of them deal with the split of the church into the established church and the Free Church of Scotland.

“This concludes with a section on the old communion vessels of the cathedral.”

The history is of Brechin Cathedral from its early beginnings up to the date of this publication and is just a brief glimpse of the events over the past 800 plus years.

The front cover is a colour rendition of a sketch drawn by R W Billings and engraved by J Godfrey in the mid 1800s.

The book is available from the cathedral office in Church Street or from News Plus in St David’s Street.

It can also be ordered via the Cathedral website which is at https://brechincathedral.org.uk/