Mystery still surrounds what happened to the stone camel which looked down upon generations of Dundee jute workers.

The ageing camel and its nine-foot high attendant were eventually dismantled 65 years ago to make way for a wider road.

Conflicting accounts

There were completely conflicting accounts of its origin and completely conflicting accounts of what became of the camel and rider after it was taken down from Bowbridge Works.

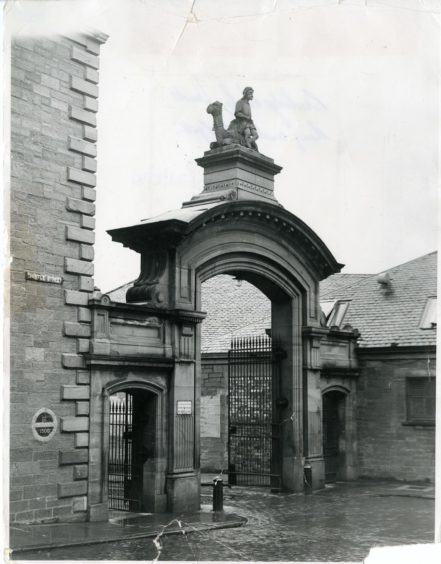

Entrance to Bowbridge Works one of Dundee’s biggest Jute mills. Stone Camel above the entrance was taken down in 1955 to make way for bigger lorries. Whereabouts thereafter unknown pic.twitter.com/Hu6WhvIyv5

— John Quinn (@jquinnsco) May 1, 2020

Dundee had developed into the world centre of the jute trade in the 19th century.

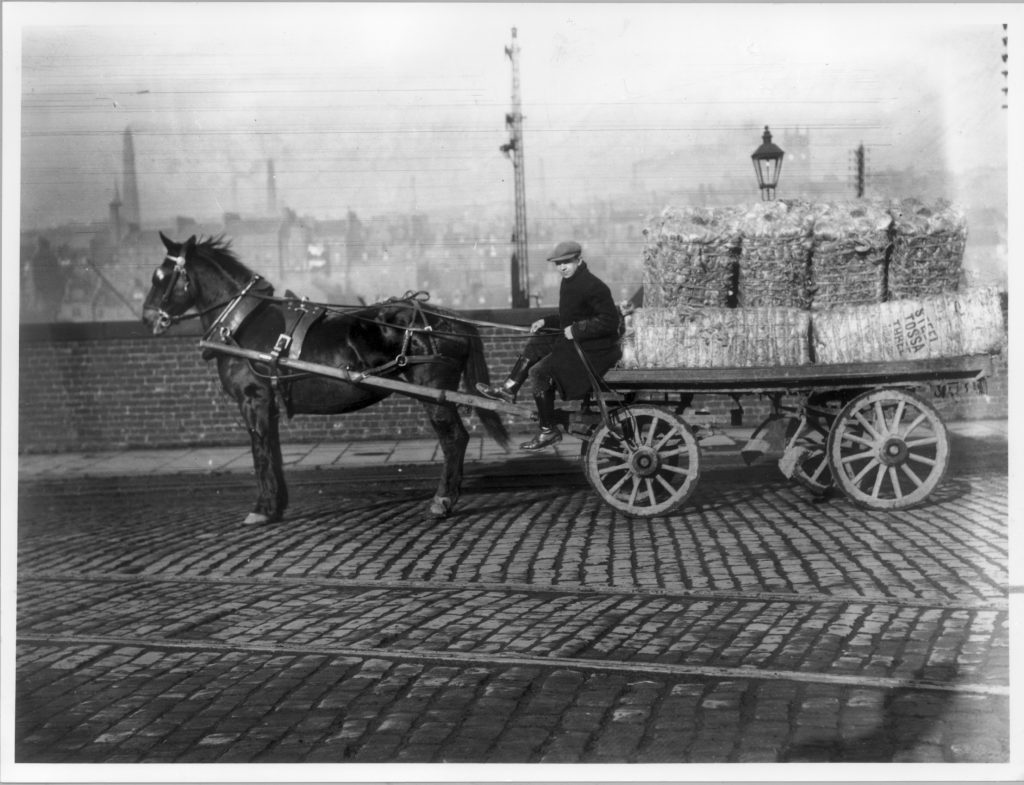

At that time, manufacturers were obtaining their supplies from London and Liverpool, but in 1840 the first consignment arrived direct from Calcutta when the barque Selma sailed into Dundee harbour with 850 bales as part of her cargo.

India’s jute brought prosperity to the city.

Bowbridge Works was built by Joseph Grimond and his younger brother Alexander Dick Grimond.

On the completion of their apprenticeship with David Martin & Company, Joseph went to Manchester in 1844 and started business as a merchant and manufacturer of oilcloth and tarpaulins.

Alexander remained in Dundee acting as the local representative for the Manchester business which was situated in Holt Town Works.

The brothers were determined to set up business on their own account in the city and J & A D Grimond was formed.

Finer jute products

Maxwelltown Works was acquired and a few handlooms introduced with half-a-dozen workers engaged.

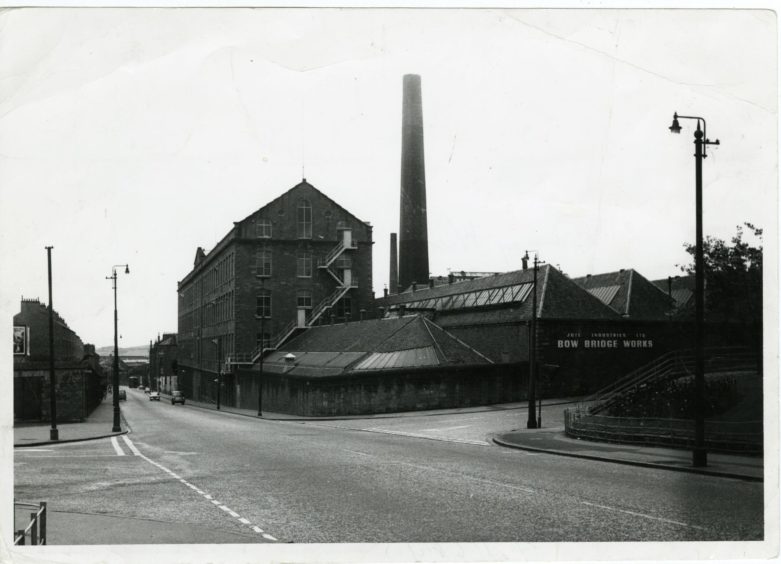

Bowbridge Works started in 1857 and the factory began to supplement the Maxwelltown Carpet Factory works in James Street in the 1860s.

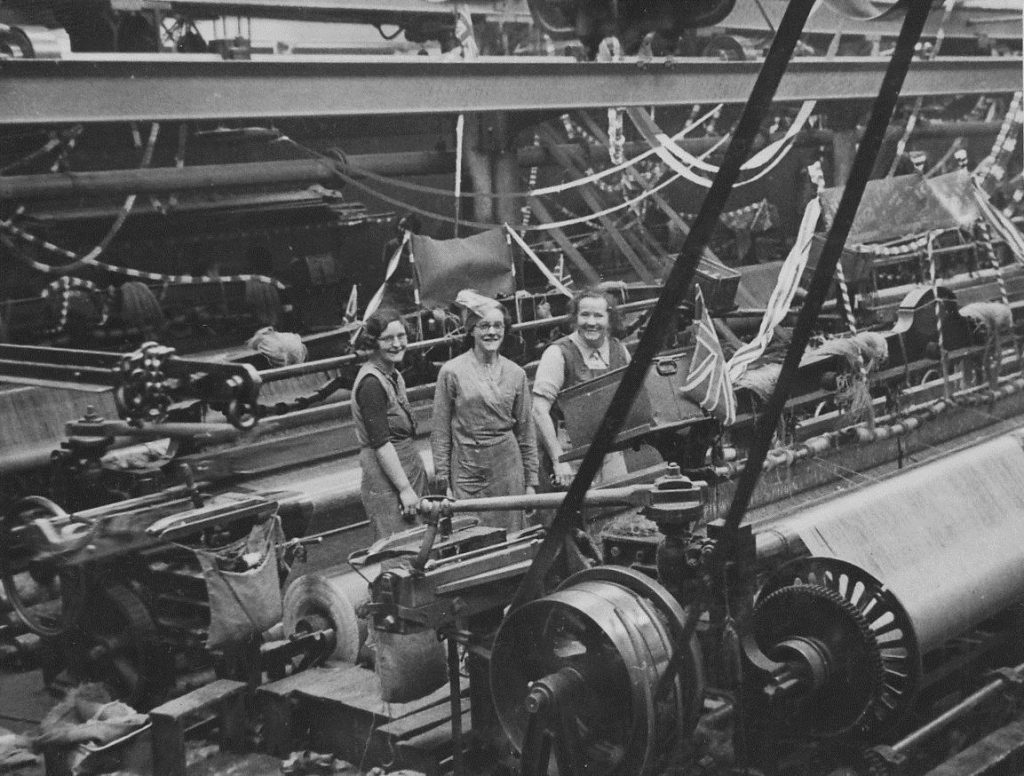

Messrs Grimond concentrated on the finer jute products like carpeting and other lines popular in the domestic market.

They devoted considerable attention to the manufacture of these carpets, and, gradually, as steam displaced hand-weaving, better classes of goods were produced.

They were among the early pioneers of the jute carpet trade and instituted the manufacture of tapestry and Brussels carpeting, also jute plushes, the richness of colouring and handsome design of which, speedily won them a high place in public favour.

There were 600 spindles at Bowbridge Works giving employment to 100 people before it was extended in 1885.

The firm had a camel’s head as their trademark and so chose a camel as the centrepiece of their gateway.

A further extension in 1891 was powered by what was then the largest engine in Dundee, a marine type triple-expansion engine of 12,000 horse power which was made in Dundee by Messrs W D Thomson & Co.

They also manufactured rope and twine.

Messrs Grimond had branches at Manchester, where they manufactured oilcloth, and at Calcutta, there was an establishment for the purchase and selection and shipment of raw material required for their extensive factories.

The firm also had offices in London and New York for the sale of their goods.

The Calcutta jute industry had captured much of the world jute trade and there were harder times ahead for the jute industry in Dundee which by now employed almost half of all workers in the city.

Appalling squalor

By 1903 nearly 3,000 workers were employed at Bowbridge Works and the establishment covered 11 acres of ground.

Conditions generally in the mills in Dundee were dreadful and the workers lived in appalling squalor.

Things were different at Bowbridge Works where the welfare of employees was looked after with a dining hall where hot meals were served at very cheap rates.

There was also a concert room and gymnasium and attached to the works was a fire engine.

The concert room was utilised by Bowbridge Works Musical Association and by a Boys’ Brigade and a pipe band.

Jute Industries Ltd was formed as a result of the amalgamation of many of the Dundee jute companies including Cox Brothers, Gilroy and Sons and J and A D Grimond.

It was registered as a limited company in 1920.

Bowbridge was extended and modernised after the Second World War.

Production work climbed rapidly with improved handling methods introduced to deal with it.

The door to Bowbridge Works was designed originally for horses and carts.

The weighbridge was just inside the door and when big articulated vehicles came on the scene it was difficult to get them in and out.

The single traffic lane through the ornamental gateway on which the camel sat was considered inadequate and the stonework had to go to make room for a wider road.

Camel dismantled

Alternative sites for the camel were sought throughout the large area covered by the works but none were found to be suitable.

Jute Industries Ltd wanted to keep the camel but were advised that it was very doubtful whether it would be possible to dismantle it sufficiently for re-erection.

When the gates were removed by Messers J B Hay they dismantled the camel on June 20 in 1955.

Bowbridge Works, founded by J &A Grimmond, 1857 employed over 3,000. Was described as a "showpiece of the late 19th

century jute industry". Majority of site demolished 1984-87. The pedestrian gate depicted Lawrence of Arabia leaning on a camel! #Archive30 #Animals #verdantdundee pic.twitter.com/k4Xy8w96I4— VerdantWorks (@VerdantWorks) April 10, 2019

They put the camel on a four-wheel bogey and it lay in Bowbridge Works for a while where staff took pictures on top of it.

A female employee was then given the bell from the camel’s neck as a keepsake by one of the managers.

The camel was apparently transported to the home of Barclay Walker of Jute Industries.

A reminder of it was embodied in the design of the new iron gates when a camel motif was worked into the metal.

But different stories over the years started to emerge about what really did happen to the camel.

There was a suggestion the camel had actually been buried in the pool behind the joinery shop adjacent to Isla Street.

The camel was variously reported to have been taken to Balgersho, near Coupar Angus, or to an estate in Inverness-shire, or even shipped to a jute mill in India.

Local historian Dr Kenneth Baxter from the University of Dundee said: “The fact that even 65 years since its removal many people still talk about the camel is an incredible testimony to its popularity and iconic status.

“Presumably the Grimonds’ intended it to make an impact, but I doubt anyone connected with the business would have predicted how big an impression it would leave in Dundonian culture.”

A letter headed “Dundee Landmark” in The Courier in August 1951 included a photograph of Thomas Doig and George Mitchell whom the letter writer stated were “sculptors and close friends who built the camel and rider on top of the gate”.

The author went on to state that Mr Doig’s business was in Victoria Road, where George Carnegie & Son, sculptors, now were.

However an alternate account appeared some weeks later from Mrs M R Marnie, Methil, who claimed her father John McNaughton of 60 Watson Street “built” the camel.

She stated that he was an employee of John McFarlane, a sculptor from Dock Street, and “went out to Fallaws Quarry every day and chipped about two tons off the huge block to enable them to lift it with the crane”.

She claimed he was on the job from the start, from the making of the plaster cast model to it eventually being put up on top of the gate.

A third account then appeared in a letter in the same newspaper which came from A McFarlane of Broughty Ferry who stated that the camel was made by John McFarlane, sculptor, Dock Street, to order from Messrs Grimond based on a photograph they supplied.

Much-talked about landmark

The letter said Mr McFarlane made a clay model which was then carved in stone in his yard by Duncan Turner, supervised by McFarlane and mounted on the gate at Bowbridge.

A fourth account provided by the Nine Trades of Dundee said it is likely that the carver of the stone was a mason named Draper.

Mr Baxter added: “So you will see in 1951, it was obviously a much-talked about landmark, but there were completely conflicting accounts of its origin.

“Interestingly the notes I had for 1955 stated that the gate had to go as there needed to be a dual carriage entrance for the works to move forward.

“However they also state that Jute Industries had been told the camel could not be taken down and successfully put back together to be re-erected.

“The photograph that exists on the day it came down suggest it was in good condition, though notably it only shows the camel, not its rider, raising the question as to whether the latter was damaged.

“I also suppose it is possible that the photograph only shows a side on view and there might have been damage to the camel that it does not show.”

Jute Industries changed its name to Sidlaw Industries Ltd in 1971 and to Sidlaw Group PLC in 1981.

The mill was demolished in 1984 and the factory buildings were demolished in 1987.

The end for the jute industry came in October 1998 when cargo ship, the Banglar Urmi, arrived at Dundee docks on the Tay from Bangladesh.

It discharged some bales of raw jute which were the last to ever come ashore in the city.

Tay Spinners, which was the last jute spinner in Europe, closed shortly before Christmas with the loss of 80 jobs.

Poem by George W. McLaren:

Oh the camel came doon,

An’ it lookit aroon,

It lookit aroon the Hulltoon.

And it said “Just you wait,

“The day it’s the gate,

“The morrin they’re hallin the mull doon”.

The mull mester replied,

“This must be denied,

“The road we hiv tae widen.

“For it’s now fufty fev,

“And if we’re to survev,

“There’s nae way that camel is biden”.

So the camel came doon,

The back end o’ June,

The end o’ auld Grimond’s folly.

And it lay in the shed,

Wi’ a bag ower its head,

Alangside the auld fire trolley.

Now it lay there for years,

Till it suddenly hears,

A voice fae oot o’ the dark.

It talked of some land,

That wiz covered wi’ sand,

And the voice calls it Tannadice Park.

Bury me deep,

And there let me sleep,

No longer the object of scorn.

Now where stands the north shed,

It lay down its head,

And that’s how The Arabs were born.

Now the mill too is doon,

And a’ roon the toon,

Is a note of dejection and pity.

For the words have came true,

But the one thing to rue,

A landmark’s been lost to the city.