It was the official investigation into the causes of the Tay Rail Bridge collapse which utterly ruined renowned engineer Sir Thomas Bouch’s reputation.

The final report of the inquiry team was delivered on June 30 1880.

Inquiry panel

An inquiry panel was set up by the Board of Trade just days after the tragedy to examine the catastrophic collapse of the Tay Rail Bridge on December 28 1879.

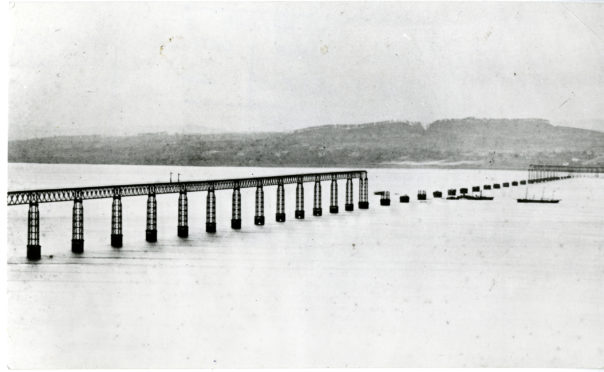

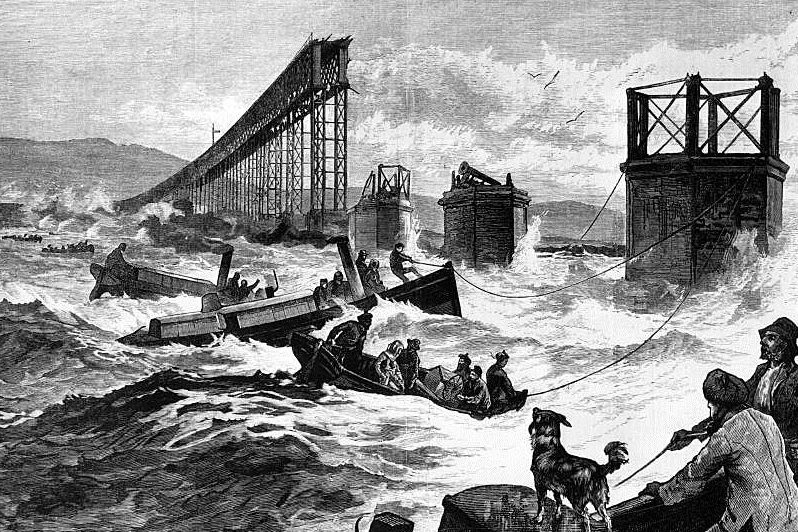

Battered by a ferocious storm, the 13 high girders of the crossing over the Tay estuary crumbled into the river below, carrying with them a train and all its passengers and crew.

Henry Cadogan Rothery, Commissioner of Wrecks, presided, supported by Colonel William Yolland (Chief Inspector of Railways) and William Henry Barlow (President of the Institution of Civil Engineers).

The three members of the court failed to agree on just one report at its conclusion.

The main report was then issued by Colonel Yolland and Mr Barlow with a second report from Mr Rothery which put the blame for faulty design, construction and maintenance at Sir Thomas Bouch’s door.

Both reports highlighted that a combination of design failures, construction and maintenance were at fault.

Iain Flett from the Friends of Dundee City Archives said the Tay Bridge Disaster would in due course be overshadowed in severity by the Armagh Rail Disaster in 1889 where 80 people died and the carnage of Quintinshill in 1915 with 227 fatalities.

“It was at the time the worst disaster in railway history in Britain,” said Mr Flett.

“Allied to the fact that Victorian engineering considered itself invincible, its effect on the public and the need to identify a ‘culprit’ could be compared to the popular incredulity that in the 20th century it was possible to have calamities like the Piper Alpha or Space Shuttle Challenger explosions.

“To also have a major government inquiry started and completed within one year is unthinkable now and virtually unknown then.

“It shows what political pressure was put on the government to find a ‘culprit’.

“We have just passed the third anniversary of the Grenfell Tower Block fire, which sadly killed a similar number of people to the fall of the Tay Bridge, and I do not see an early resolution to its findings in sight.”

The bridge was built by Hopkin Gilkes and Company, a Middlesbrough firm which had worked previously with Bouch on iron viaducts.

Gilkes, having first intended to produce all ironwork on Tees-side, used a foundry at Wormit to produce the cast-iron components, and to carry out limited post-casting machining.

Lack of understanding

The unsoundness of the castings was, no doubt, one of the causes of the collapse, and this was produced by the employment of a very low class of Middlesbrough iron.

There also appears to have been a lack of understanding of the relative properties of iron and steel.

Mr Flett said cast iron is durable and strong in construction where gravity has to been contended with, and the fact that sound girders from the first bridge were pushed by ram onto the current Tay Rail Bridge underlines that point.

Cast iron, however, is not good for flexing tension and stress and the cast iron lug holes were a bad fit and did not sustain the flexing and pressure put upon them in a windy estuary.

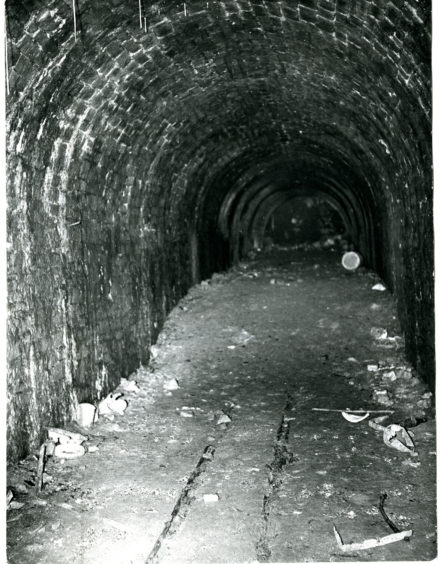

The original idea was to build the bridge on brick columns, but, owing to some blunder in the making of the foundations, it was found necessary to make a change, and to erect iron columns instead.

Mr Flett said: “This was due to an insufficient geological survey, which was a common problem in Victorian times.

“Fifty years previously the Dundee-Newtyle railway was almost bankrupted because they had not anticipated the difficulties of tunnelling through the volcanic rock of the Law.

“Ninety years later Duncan Logan would hit problems with the coffer-dams for one of the road bridge pillars on the south side of the river, and most recently the surveys of the river bed meant that the jewel of the V&A museum had to stay mostly on land and not edge out more than it does into the Tay.”

Those iron columns on the Tay Rail Bridge were of such bad design, and so imperfect in construction, that they were unable to sustain the weight required of them.

The original report went on to point out that there was no proper supervision over the bridge after it was erected; that the ties of the cross-bracings had been tightened up and brought up to their bearings before the date of the inspection by General Hutchinson, and that the fact that so many of them became loose was an evidence of weakness in this part of the structure.

Then they said: “That notwithstanding the recommendations of General Hutchinson that the speed of the trains on the bridge should be restricted to 25 miles per hour, the Railway Company did not enforce that recommendation, and much higher speeds were frequently run on portions of the bridge.

“That the fall of the bridge was occasioned by the insufficiency of the cross-bracing and its fastenings to sustain the force of the gale on the night of December 28th, 1879, and that the bridge had been previously strained by other gales.”

Rothery’s report, however, was forthright in its condemnation of the structure and in stating who was responsible for the accident.

Sense of duty

Mr Rothery went on to state that he thought it was their duty to call attention to certain defects in the design which rendered the structure weak and thereby contributed to its fall.

He said: “It seemed to me, also, that we ought not to shrink from the duty, however painful it might be, of saying with whom the responsibility for this casualty rests.

“My colleagues thought that this was not one of the questions that had been referred to us, and that our duty was simply to report the causes of, and the circumstances attending, the casualty.

“But I do not so read our instructions.

“I apprehend that if we think that blame attaches to anyone for this casualty, it is our duty to say so, and to say to whom it applies.

“I do not understand my colleagues to differ from me in thinking that the chief blame for this casualty rests with Sir Thomas Bouch; but they consider it is not for us to say so.

“The conclusion to which I have come is that this bridge was badly designed, badly constructed, and badly maintained, and that its downfall was due to inherent defects in the structure which must, sooner or later, have brought it down.

“For these defects, both in the design, the construction, and the maintenance, Sir Thomas Bouch is, in my opinion, mainly to blame.

“For the faults of design he is entirely responsible.

“For the faults of construction he is principally to blame, in not having exercised that supervision over the work which would have enabled him to detect and apply a remedy to them.

“And, for the faults of maintenance, he is also principally, if not entirely, to blame in having neglected to maintain such an inspection over the structure as its character imperatively demanded.

“I think, also, that Messrs Hopkins, Gilkes & Co are not free from blame for having allowed such grave irregularities to go on at the Wormit Foundry.

“Had competent men been appointed to superintend the work there, instead of its being left almost wholly in the hands of the foreman moulder, there can be little doubt that the columns would not have been sent out to the bridge with the serious defects which have been pointed out.

“The great object seems to have been to get through the work with as little delay as possible, without seeing whether it was properly and carefully executed or not.

“The company also are, in my opinion, not wholly free from blame for having allowed the trains to run through the high girders at a speed greatly in excess of that which General Hutchinson had suggested as the extreme limit.

“They must or ought to have known, from the advertised time of running the trains, that the speed over the summit was more than at the rate of 25 miles an hour, and they should not have allowed it until they had satisfied themselves, which they seem to have taken no trouble to do, that the speed could be maintained without injury to the structure.

“It remains to inquire whether the Board of Trade are also to blame for having allowed the bridge to be opened for passenger traffic when they did.

“After what has come out in the course of this inquiry, it is clear that there can be no justification in future for disregarding altogether, as it seems to have been done, the effect of wind pressure on such a structure as this.

“But, whether General Hutchinson is or is not to blame for having so done, Sir Thomas Bouch is not relieved from his responsibility.”

Highly credible

Liberal Party MP George Anderson said Mr Rothery “boldly took the thing in hand and proceeded to apportion the blame” which was highly credible to him.

He said hardly anyone believed the Tay Rail Bridge could be built for £350,000 and he heard that it ruined the first contractor because the sum was so small.

“Afterwards, the company had to hand it over to another contractor; but what had turned out to be the case was very evident from the first—namely, that in order that any contractor might make the thing pay, the work had to be scrimped and scamped from the very beginning and all through its stages,” said Mr Anderson.

He was informed that the Canada Bridge at Montreal was exactly of the same length – two miles – and it cost over £1,000,000 of money, and yet it was proposed to build the Tay Bridge, at a time when prices for iron were exceedingly high, for £350,000.

“Well, when the bridge was built, it was looked upon with considerable suspicion,” he said.

“Many of the inhabitants of the neighbourhood refused to travel by it; they would send their goods and coals over it, but they would not trust themselves upon it.

“Things went on safely for a time; but, on the 28th December last, a gale came that was too strong for the structure.

“The result was that the bridge broke down, and a train full of people was hurled down into the river – into a certain and instant death.”

Forgone conclusion

He said the collapse of the bridge “was a forgone conclusion” and some of the parties who built the bridge “with such insufficient work, and with such insufficient care” ought to be, he believed, standing in a criminal dock to answer for their neglect.

First opened in 1878 to much fanfare, the bridge was the longest in the world at the time.

The bridge took six hundred workmen six years to build.

It consumed 3,700 tons of cast iron, 3,500 tons of malleable iron, 87,000 cubic feet of timber, 15,000 casks of cement, 10 million bricks and more than two million rivets.

Bouch “never forgave himself” and died just four months after the report was published.

It was another nine years before the second Tay Rail Bridge was opened to a more subdued celebration.