On September 7 1940, the calm Saturday evening of Stonehaven was shattered by the urgent pealing of church bells… the Nazi invasion feared since Dunkirk had started on Scotland’s north-east coast.

The army code word for a German landing, Cromwell, had been given.

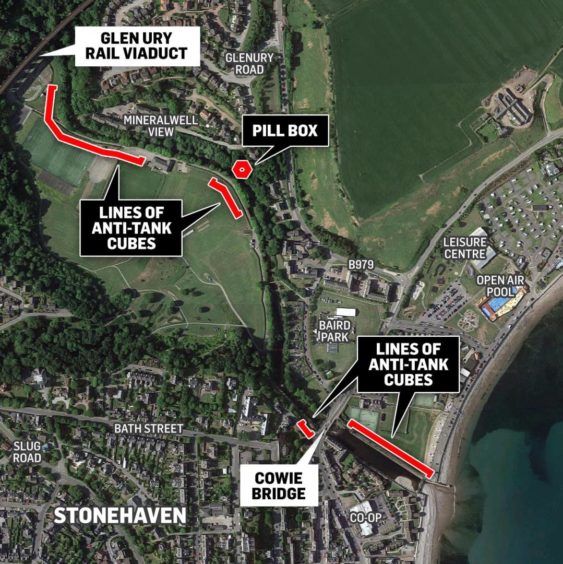

Army units had orders in the event of invasion to scramble to Stonehaven and halt the invaders by blowing up bridges, creating road blocks and – most importantly – manning the Cowie Stop Line.

The formidable defence work of pill boxes, anti-tank cubes, tank traps, ditches, and reinforced banks was built in the summer of 1940 and ran more the 5km along the Cowie Water then out into the Grampian foothills.

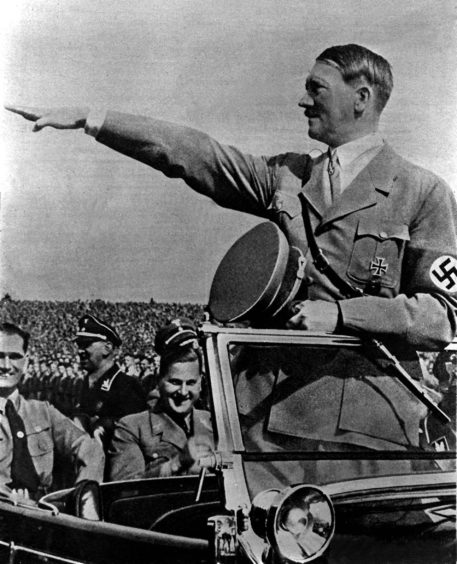

It was here, on the north-east’s version of the Maginot Line, the battle would to rage to halt the columns of German Panzers and troops from sweeping south in a blitzkrieg to establish Hitler’s Third Reich in the UK.

Except it didn’t. The warning of the Nazi invasion that night was a false alarm, given in error.

It’s an episode from World War Two that might have been lost in time – except for the visible remains of anti-tank cubes that can still be seen around Stonehaven as people stroll, jog or walk their dog around the town, including the quiet green space of Dunnottar Woods.

But defence archaeologist Gordon Barclay says 80 years ago, this would have been a very different scene and a very different atmosphere. Britain was reeling from Dunkirk and the Nazis had just swept across Norway.

“The military fear of an invasion of Britain was real. At the time, they really did think they were coming. They thought if the Germans had got to this stage, defeating France, the Netherlands and Poland in a few weeks, they must have planned an invasion,” he said.

“The atmosphere among people would have been one of great concern. It’s quite clear from the documents that work was going on flat out to build defences. It was fairly panicked.”

The expectation was a German invasion would be on the south coast of England, with the greatest preparations made around Kent and Suffolk.

But there was a real fear that Hitler, having just swept across Norway, would choose to invade on one of the wide-open and easily accessible beaches of the north-east.

The Germans spent a lot of energy

spreading false information to give

us the impression there was an

invasion coming from Norway.”

“The Germans spent a lot of energy spreading false information to give us the impression there was an invasion also coming from Norway, or that might be the invasion,” said Dr Barclay.

Hitler’s commanders wanted to lure forces north away from Kent and Sussex to leave those defences weaker.

British Army commanders drew up a list of beaches vulnerable to invasion along the east coast of Scotland.

“That includes Stonehaven itself, then there was cliff all the way up to Aberdeen, just south of Nigg, Aberdeen itself, then the long beach all the way up to Newburgh, then north again round to Fraserburgh,” said Dr Barclay.

All these holiday beaches

were being covered with

anti-tank cubes, pill boxes

and huge amounts of barbed wire.”

“Nobody knew which was more likely, so that was why all these holiday beaches were being covered with anti-tank cubes, pill boxes and huge amounts of barbed wire.

“You couldn’t go on to them, you couldn’t go swimming.

“There would be fences and guards to stop people going on to the beach.”

The relatively flat land of the Mearns and Angus would offer little resistance to the armour and troops of German invaders. Stonehaven, though, offered a bottleneck and so the Cowie Line came into being.

Dr Barclay said: “The Cowie Line was to stop any German forces that landed on the sandy beaches north of Aberdeen or over Elgin way getting south into Angus.”

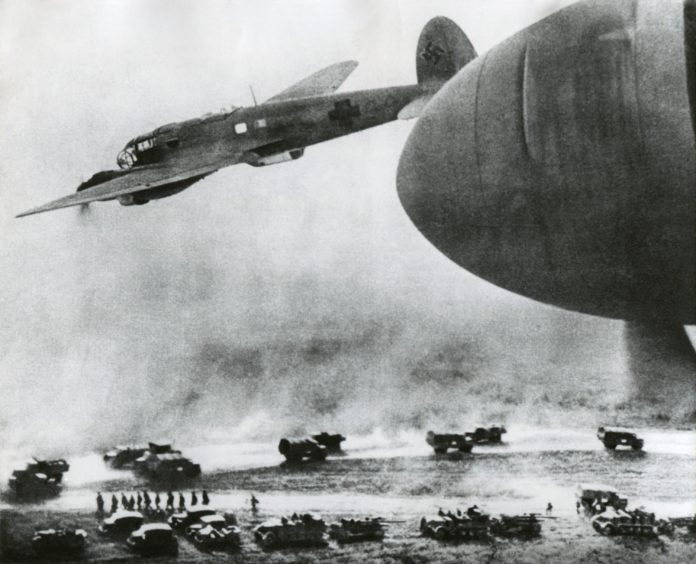

“If we turn to what had happened in France and Flanders, the Germans had developed a new form of warfare, highly mobile armoured warfare. It had cut the Allied armies to bits. It was like a flyweight boxer dancing round a slow moving heavyweight, landing blows while the heavyweight couldn’t hit back,” said Dr Barclay.

“There was a concern if the Germans had invaded, there would be very little that would stand up to their new form of warfare, if they managed to land tanks. The stop lines were anti-tank obstacles drawn across the country, all over eastern and southern Britain, to try to stop fast-moving German armoured columns, long enough for relatively slow moving British reserves to be brought up to face them.”

The Cowie Line was built by Royal Engineers and the Pioneer Corps along with private contractors and council workmen.

It ran along the beach to the mouth of the Cowie Water and on to Durris until the natural barrier offered by the Grampians foothills, with more reinforced defences at Bridge of Dye, the Devil’s Elbow and Drumochter.

Banks on the Cowie were built up and reinforced. Anti-tank cubes were put down, ditches were dug and camouflaged pill boxes put in place.

But for all its name, the stop line was never intended to stop German tanks, but to slow them down.

None of these defences were

ever intended to stop anything

for more than a few minutes.”

“None of these defences were ever intended to stop anything for more than a few minutes. They were there to delay it long enough you that you could bring fire to bear on it, stop it moving, immobilise it,” said Dr Barclay.

“There was a thing called the Boys anti-tank rifle which could penetrate a limited amount of armour. They could bring mortar fire to bear on it, or even an anti-tank gun if they were lucky enough to have one of those.”

The line was only part of the defensive plan. Road and rail bridges were to be blown up, including at one point the train track across the Glenury viaduct in Stonehaven to stop tanks crossing it. This was later changed to being blocked rather than destroyed, to allow defenders to counter-attack the Germans.

Dr Barclay said: “Because the Cowie Water was an anti-tank obstacle, the most vulnerable points were where the road crossed the river. So they were prepared to either blow the bridges or have road blocks, involving steel railway or tramway rails laid across from concrete block to concrete block.

“The pill boxes were concentrated at these road blocks so machine gun fire could be brought to bear on anyone trying to dismantle the road blocks to let tanks through.”

Had Scottish Command received the code word Cromwell, it would have dispatched a battalion from Fifth Division to secure the crossings at the Cowie Water, some 600 or 700 would man the Cowie Line.

Finally, by the end of 1940 the Cowie Stop Line was complete. And obsolete.

“Younger commanders, having had rings run round them in France, were determined they were not going to sit behind defences waiting for the enemy to come. Their defence plans were made, but they basically abandoned the lines. Their defences were much more imaginative and complex rather than just sitting waiting in pill boxes.”

Dr Barclay doubts the Germans were planning an invasion in 1940, anyway.

In fact, the Germans were surprised by

how quickly they had conquered France

and had no plans in place to invade Britain.”

“In retrospect the chances of an invasion were very slight. In fact, the Germans were surprised by how quickly they had conquered France and had no plans in place to invade Britain.

“But the Germans did a lot of work to give us the impression they were coming and Hitler gave orders an invasion was to be prepared for. Indeed barges were gathered in the Channel ports. But a lot of people think this was to try to bring Britain to the conference table.”

While, thankfully never needed, the Cowie Stop Line did serve one invaluable wartime service.

“Some people have said all the building of defence was as much about psychology as about physical defence,” said Dr Barclay.

“It was proving to people

we were actually going

to stand and fight.”

“It was proving to people we were actually going to stand and fight.

“We weren’t going to go to the conference table, surrender and negotiate a peace. We were going to fight.

“It’s very much a reflection of the government’s position after Churchill took over.”

Today much of the remains of the Cowie Stop Line is protected as scheduled monuments, deemed by Historic Environment Scotland to be of national importance.

In fact, it was Dr Barclay who scheduled them when he was the area inspector of ancient monuments for Historic Scotland in 1996.

He walked the entire line, recording everything that had been left in place.

Dr Barclay also wrote a paper on the Cowie Stop Line for the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. You can read it here.

No map has ever been made of the Cowie Stop Line and new elements are still being discovered to this day.

The monument has a significant place in the national consciousness as a tangible and powerful reminder

of a defining event of the 20th century.”

The Historic Environment Scotland schedule for the Cowie Stop Line says: “The monument has a significant place in the national consciousness as a tangible and powerful reminder of a defining event of the 20th century”.

And one that could have been even more so, if the church bells of Stonehaven had rung out in earnest on September 7 1940.