It was set to be just a routine night shift for the men of Stonehaven Coast Radio Station, dealing with the chatter and communications in its role as the lifeline between sea and shore.

Then, shortly after 10pm came the distress call. It was Piper Alpha.

A violent blast had ripped through the structure and the mayday sent from the platform, 120 miles north-east of Aberdeen was being picked up by the coastal radio station, nestling above the Mearns town.

“When the Piper sent out its mayday signal… it was such a sudden thing to happen.

“There was just no expectancy of it,” said Eddie MacRae, one of the radio operators on duty in Stonehaven that fateful night on July 6 1988.

“It was quite frightening. Anybody sitting at their desk and gets a message like that gets an urge of self-panic. You didn’t want to get anything wrong, you wanted to get as many of the facts, as dead accurate as you can.

“Keeping it calm and professional was one of the main things. Although the old ticker was ticking away, you had to be accurate.”

He said both Stonehaven and Wick radio stations first heard the distress call and became central in helping coordinate the response to the disaster, with officers at Wick Radio Station directly handling the distress.

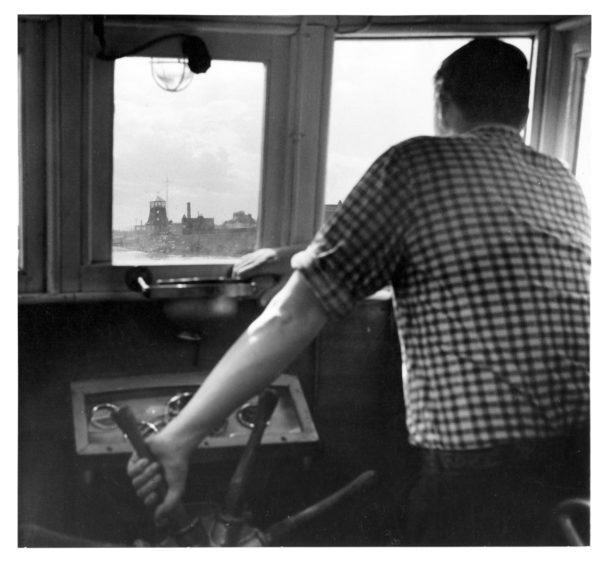

As the horror and drama unfolded on Piper Alpha, Stonehaven was key in handling back up communications between rescue and support vessels scrambled to the scene.

One of them, the Tharos, was kept on a continuous call from 11pm to 4.30am the next morning.

The Tharos, a firefighting and rescue ship was a key player that night.

It used its water cannon where it could, but eventually it was driven back by the heat of the blaze.

As the awful night went on, the Tharos took on casualties picked up by standby vessels and an RAF rescue helicopter. Onboard paramedics treated the injured. It was from the Tharos that the first helicopter left with casualties for Aberdeen Royal Infirmary.

It was a harrowing experience for the radio station officers having to listen to the communications, learning through the airwaves of the enormity of the disaster, the scale of the loss of lives, hearing the desperate efforts to save survivors.

Mr MacRae said he almost automatically knew just how disastrous events were on Piper Alpha.

“Most of the lads at one time had a trip out to a rig and realised just how many people were involved. The explosion would have been so bad, I thought then a lot of people would have had to jump over the side to get off the rig.

All you were thinking as an operator was

get the messages from them and deliver

them to who needs to know.”

“And we had got to know the voices of the operators on the rig.

“But you didn’t think about that at the time. All you were thinking as an operator was get the messages from them and deliver them to who needs to know and make broadcasts. Whatever information we got we had to re-broadcast. That was the whole idea of having operators ashore, so we could deal out the messages to shipping and whoever was involved.

“Every little change that happened had to be reported to all these addressees.”

By the time the rescue operations stood down, 167 men were dead and 61 workers escaped and survived.

Piper Alpha was one of the most dramatic and moving moments in the history of Stonehaven Radio Station, that transmitted for the last time 20 years ago on June 30 2000.

The day the station, call sign GND, fell silent it brought to an end a slice of history which began 90 years before, according to Ally Taylor, station manager when it closed down.

The first radio station in the Stonehaven area was built in 1910 and was actually three miles south at Criggie and is today a house – still called the Old Wireless Station, said Mr Taylor.

It was mainly used as a telegraphy station, passing messages across the country and between continents.

Mr Taylor said: “In 1942 during the war the Admiralty decided that coverage for shipping from coast radio stations at Wick and Cullercoats (on the Tyne) didn’t give them the required coverage, so wooden huts were built to house radio equipment on the fields up from Dunnottar Castle. This station was run by the Admiralty and was used for transmitting and receiving vital wartime information to and from shipping.

“Ships had to keep radio silence so the enemy couldn’t track them. So they kept receiving watches for coded messages sent via the coastal radio stations. The only time they broke silence was when they were attacked,” said Mr Taylor adding there were different codes for whether they had been torpedoed or attacked by surface vessels.

“The coast stations would pass any such messages to the Admiralty. The role of the coast stations would be to receive such messages and send out coded messages from the Admiralty to shipping.”

In the post-war years GND entered a new chapter of its history as a vital part of the coast radio station network across the UK, keeping a distress watch, handling mayday calls and coordinating rescue operations, working with the Coastguard and RNLI.

By this time, it had been taken over by the Post Office and was also handling the extensive commercial messages for trawlers, including the fleets of Grimsby and Hull making their way to the lucrative, but perilous fishing waters of the White Sea.

Communications with trawlers was to be a key part of the station’s life for much of its history.

They sent information about the big catches

in code, so nobody else could translate

how much fish they had caught.”

“In the old days the fishing vessels had top-notch radio operators,” said Mr MacRae, 84, who worked at the radio station for 20 years until just before it closed.

“So they sent information about the big catches in code, so nobody else could translate how much fish they had caught.”

By 1947 the cluster of huts and masts on the fields by Dunnottar were not fit for purpose and a new station was planned.

The 1958 building is the one that stands today, its polygonal ribbon window main structure looking like an airport control tower. A date stone, 1956, marks when construction started on what was, at that time, one of the most modern in a string of coastal radio stations linked up across the UK.

For the next 14 years, the station handled safety of life at sea (SOLAS) communications. It kept distress watches on both Morse code and radio frequencies. Officers would transmit essential weather and navigational warnings to ships in their area, said Mr Taylor.

The station was also the hub for commercial messages and radio links between ships and their companies, or even putting phone calls from crew members through to their loved ones in their homes.

“All this time of commercial traffic the radio stations around the coast still had a main objective of keeping the distress watch on Morse and radio on behalf of Her Majesty’s Coast Guard, saving many lives and ships throughout the years,” said Mr Taylor.

By the early 1970s, however the Post Office had considered axing Stonehaven out of its maritime radio station network. Then came oil.

As the black gold rush blossomed, so did the rapid need to coordinate communications in speech and radio telex for the oil industry. GND lived to broadcast another day.

The bulk of the work we

did then was servicing

the oil industry.”

On some days, Stonehaven staff, working shifts to cover 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, were handling more than 700 radio link calls a day, said Mr Taylor. Other stations around the coast were dealing with a similar volume.

It was during this time, Gordon Reid worked as a radio officer at Stonehaven.

“The bulk of the work we did then was servicing the oil industry,” he said.

“A lot of the fields were still being assembled and we did a lot of the link calls for the business and the crews calling home. This was obviously before mobile phones. At that time we were the backbone of voice communication. There was also Telex, with links to quite a few of the platforms.

“At one period we were the lifeline between offshore and onshore, before satellite and oil companies started using their own communication links. It started fading away when I left in the mid-80s.”

Mr Reid said there was a great camaraderie in the station, with officers socialising with each other and their families.

However, as the years rolled on satellite communications and mobile phone technology advanced exponentially.

Every year at the end of June…

we have a wake at the Station Hotel

where ex-radio station staff get together

for a few drinks and a reminisce.”

By 1999 it was clear the old days of “steam radio” were numbered. BT (formerly the Post Office) shut down GND on June 30 2000.

The occasion was marked with a dinner at Stonehaven’s Station Hotel, attended by past and present station staff, offshore radio operators and senior management. It started a tradition that continues to this day.

Mr Reid said: “Every year at the end of June, apart from this one with Covid, we have a wake at the Station Hotel in Stonehaven, where ex-radio station staff get together for a few drinks and a reminisce.”

But Stonehaven Radio Station is a survivor. Today it might stand empty and boarded up, but there are plans to bring it back to life and on a new frequency – as a brewery and visitor centre.

The man behind the vision is Robert Lindsay, founder of Stonehaven’s Six Degrees North brewery.

“Six Degrees North have acquired the site and we are hoping to develop it into a small brewery and visitor centre,” he said.

“We think that would attract people to the area and bring life back to an iconic Stonehaven building, complementing that of our neighbours at Dunnottar Castle and the wonderful seaside town of Stonehaven.”

Mr Lindsay said it is an ongoing project and a feasibility study has been carried out.

“The radio station is quite dear to quite a number of local people. Obviously it has a historic significance, so from our perspective we hope to still be able to maintain some of that history and exhibit some of the goings on that happened there over the years.”

Tuning in to Stonehaven Radio Station… and Colin Clyne

Of its many claims to fame, perhaps the most unusual is that Stonehaven is the only coastal radio station ever to have a song written about it.

Award-winning singer-songwriter Colin Clyne penned Stonehaven Radio Station and Me as a tribute to the trips he made as a boy to follow the Dons, with his uncle and his radio station colleagues.

The away games were basically him

and a bunch of the guys who worked

at the radio station with him following the Dons around Scotland.”

“I used to go and watch Aberdeen in the 80s and my uncle used to take me to home and away games,” said the country, folk rock and Americana star, who was born and raised in Stonehaven.

“The away games were basically him and a bunch of the guys who worked at the radio station with him following the Dons around Scotland.”

However, the story behind the song and what happened to his uncle, George Reid, isn’t quite so upbeat.

“We went to an away game where we had beaten Hibs three-nil in a semi-final, I was quite young, under 10. Opposing fans were coming the other way and one of them came up to my uncle to wish him good luck in the next round and promptly head-butted him.

But it also touches on some the

games we went to, like the

Scottish cup final of 86 and

Gothenburg and things like that.”

“I ran up to a policeman for help, because I was young and that’s what I expected, but I was basically waved away. So the song was inspired by that feeling of authority figures and places of safety that as a child you believe in, but are not truly there.

“But it also touches on some the games we went to, like the Scottish cup final of 86 and Gothenburg and things like that.”

Colin has clear memories of his days away with his uncle and his pals.

“They would pull up in a camper van after the game to a pub and because I was quite young I was left, with another girl, and someone would eventually come out with some Coke and some crisps. The same story thousands of other people my age had going to the football as a young kid.”

Stonehaven Radio Station And Me was

actually recorded in California with myself,

an American and Mexican – but during

the recording I wore a Gothenburg 83 strip.”

Those memories helped Colin pen a memorable song in his music career. He spent 10 years living and working in California where he worked among legendary producers and created two albums, Doricana in 2010 and The Never Ending Pageant in 2014.

He collaborated on them with Grammy-winning engineer Alan Sanderson, who worked with Michael Jackson, the Rolling Stones, Elton John and Madonna.

“Stonehaven Radio Station And Me was actually recorded in California with myself, an American and Mexican – but during the recording I wore a Gothenburg ’83 strip.”

Colin is now back living and working in Aberdeen and getting his music career up to speed.

“I took a break a while back in 2016. I had been hammering at it for 10 years solid and was going to take three months off, but it ended up lasting three years. I was still writing and trying to produce, but I went back and started playing again last year.

It gets played at Pittodrie most home games.

I thought it might have happened once or twice,

but effectively for the past three seasons

it has been getting played.”

“I have recorded a new single being released in August, called Where The Ships Go To Die. The intention is to do an album next year.”

As for Stonehaven Radio Station And Me…

“It gets played at Pittodrie most home games,” said Colin. “I thought it might have happened once or twice, but effectively for the past three seasons it has been getting played.”