The RAF was the first line of defence when the Battle of Britain started 80 years ago.

Fighter ‘aces’ became national heroes.

A pilot became an ace after being credited with five enemy aircraft destroyed.

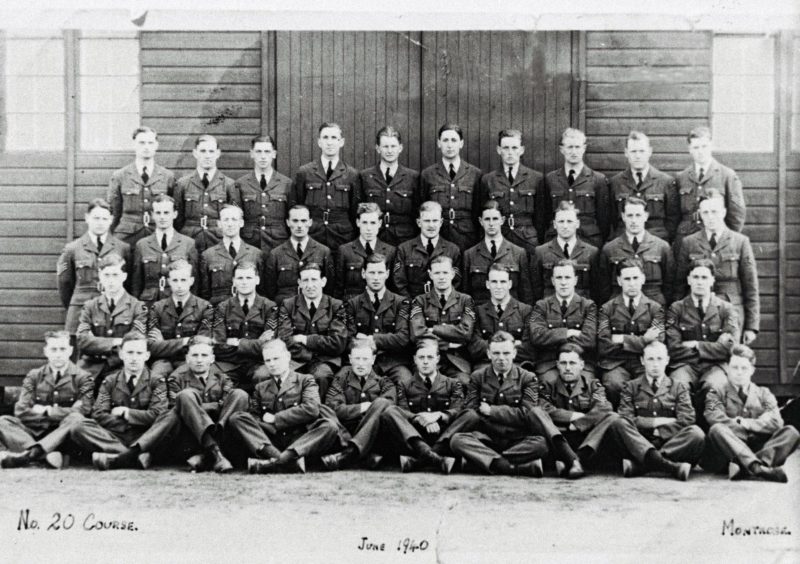

Some of these aces were from the 140 men who trained at RAF Montrose and fought in the battle.

The Battle of Britain, which took place in 1940, was later given official dates which were from July 10 to October 31.

Aircrew who had flown at least one operational mission between these dates were awarded the Battle of Britain clasp to their 1939-1945 Star War Medal and 2,900 men qualified.

Taking up the story, Dr Dan Paton, the curator of Montrose Air Station Heritage Centre, said these dates neglect the aerial fighting that had been taking place since the very start of the war in what might be called the Battle of Scotland.

“The first RAF casualty of the war was Lt ‘Tiny’ Burrell of No 269 Coastal Command Squadron flying from Montrose on September 6 1939,” he said.

“The first Distinguished Flying Medal (DFM) of the war was awarded to his navigator who flew their Anson home over the body of his dead pilot.

“The first civilian casualty of enemy bombing was in Orkney.

“The first German aircraft to be brought down on British soil was a Heinkel 111 bomber shot down by Spitfires of No 603 (City of Edinburgh) Squadron.

“Scotland was in range of Luftwaffe bombers flying from Germany and later Stravanger in Norway.

“No 603 Squadron stationed at Dyce and Montrose gained valuable combat experience and shot down several German aircraft.

“In August they were posted to Biggin Hill at the heart of the RAF effort in the Battle of Britain.

“There the German bombers were arriving in large formations, escorted by German fighters.

“Casualties soon mounted.

“Richard Hillary, who later achieved fame by writing of his experiences in The Last Enemy, one of the classics of the air war, was shot down and badly burned, the fate of many fighter pilots.”

The cigar-smoking former Dundee MP Winston Churchill was the recently appointed Prime Minister when he warned the House of Commons that the Battle of Britain was about to begin.

“The whole fury and might of the enemy must very soon be turned on us,” said Churchill.

“Hitler knows that he will have to break this island or lose the war.”

Churchill’s eloquent call to fight on alone still inspires but at the time his political position was precarious.

He had the support of the Labour party but many Conservatives mistrusted Churchill and a significant number favoured a negotiated peace.

In the circumstances that seemed to many the only realistic course.

The situation facing Britain in June was indeed desperate and had never been envisaged or planned for.

Nobody expected that the French army of 83 divisions, which had resisted the Germans for four years in World War One, would collapse in a matter of weeks, or that the whole of the North Sea coast from Norway to Denmark, Holland and Belgium would be occupied by Germany.

Worse still, the victorious German forces in occupied France had only to cross the Channel to invade a country whose defeated army had lost all its weapons and equipment at Dunkirk.

The extraordinary thing is that this did not result in a wave of defeatism as had happened in France.

The British people did not accept that they had lost the war.

In earlier wars Britain would have turned with confidence to the Royal Navy, the greatest fleet in the world, to repel any attempt at invasion but warfare had changed.

Huge advances in aviation meant that no fleet could operate without air cover.

Command of the Air had superseded Command of the Seas.

But how well prepared was the RAF?

At RAF Montrose, Tom Neil was a member of No 15 Course and got his coveted wings in May 1940.

His flying training had been entirely on biplanes like the aircraft of the First World War.

He left Montrose to join a squadron flying Spitfires, the RAF’s most modern fighter, having never flown a monoplane.

Within a few months he was in the thick of the Battle of Britain, flying Hurricanes and by the end of the battle he was a fighter ace, having shot down eight German aircraft.

Dr Paton said the bigger picture was more complicated and took the story back to 1935 when the threat from German re-armament began to be recognised.

This resulted in a series of Expansion Acts of Parliament to expand and modernise the RAF.

At the end of the First World War the RAF, then the largest air force in the world, had been reduced to a small force, mainly employed in policing the Empire.

Montrose was one of many air stations that were closed but it had remained unaltered.

In 1935 the RAF sent an advance party.

New accommodation and service buildings were quickly erected using standard RAF wooden huts and the old World War One hangars were re-instated.

In less than a year RAF Montrose was operational again and re-opened on January 1 1936 as No 8 Flying Training School.

Even the Commanding Officer was familiar.

Group Captain Hugh Vivian Champion de Crespigny had been OC of RAF Montrose when it closed.

In the same year an important reorganisation of the RAF created new Functional Commands, Bomber Command, Fighter Command, Coastal Command and Training Command.

The most important requirement to expand an air force is trained men.

By 1940 Tom Neil was one of 400 pilots trained at Montrose ready to face the might of the Luftwaffe.

He recalled that his flying training was thorough, but still based on the methods of the First World War.

However, more of these pilots were trained to fly bombers rather than fighters.

The custom at Montrose, when a new course arrived, after completing their elementary flying training, was to line them up.

The Chief Flying Instructor, accompanied by his entourage, would go down the line and ask: “Do you want to fly fighters or bombers?”

This being the RAF not everybody got their choice.

Six months before the start of the Battle of Britain only 15 men out of 40 were selected for fighters.

This reflected the convictions and priorities of the heads of the RAF.

They believed that bombing could destroy the enemy’s industry and the population’s will to fight and that air power alone was enough to win a war, without the need for ground troops or naval forces.

Priority was given to bombers.

Fighters, a defensive weapon, were secondary.

This was the situation facing Air Marshal Dowding when he was made OC Fighter Command in 1936 and set out to modernise Fighter Command.

In 1936, all the RAF’s fighter squadrons were equipped with biplanes so there was an urgent requirement for modern fighters.

The prototype of the Hawker Hurricane first flew in November 1935.

The Hurricane was a modern design, a monoplane with retractable undercarriage but in construction was still a development of the fabric covered biplanes that were in service at Montrose in the 1930s.

The Spitfire, which first flew in March 1936, was a more radical design and encountered serious problems in manufacture which delayed its introduction into squadron service.

It was the Hurricane which equipped most RAF squadrons in the Battle of Britain.

Fighters like these had a short range and a system for intercepting the enemy which depended on flying patrols which soon wore out both pilots and aircraft.

Dowding heard about the work of Robert Watson-Watt in using radio waves to detect aircraft at long range.

The eventual outcome was the creation of a system giving early warning of the approach of enemy aircraft.

Watson Watt, who was born in Brechin, not only showed the technical feasibility of radar, he organised the construction of a network of radar installations linked to an organisation able to transmit the information through the chain of command so that RAF officers could see on their plotting table the approach of the enemy, their speed, direction and approximate number.

They could then phone their instructions directly to the squadrons whose aircraft, fitted with two-way radio, were always in touch with their controller on the ground.

By February 1940, 32 Chain Home radar stations and 12 Chain Home Low stations designed to detect low flying intruders were operational.

The Chain Home station at Douglas Wood near Dundee and the Chain Home Low station at St Cyrus show that the network was not confined to the south of England.

In addition, there was an extensive network of Observer Corps units, manned by 30,000 volunteers who became expert at aircraft recognition and tracking the enemy visually, reporting directly by telephone to their nearest control centre.

Douglas Wood was capable of locating aircraft up to 150 miles distant over the North Sea and giving range and bearing, also recognising friendly or enemy aircraft.

By 1940, Fighter Command had modern fighters and the world’s first early warning system which made it possible to see the enemy attack at an early stage, to scramble fighters to intercept and to control the battle.

There were improvements that continued to be made right up to August 1940.

Constant speed three bladed propellers, which greatly enhanced performance, replaced the fixed pitch wooden propellers.

Armour protection for pilots was installed.

De Wilde armoured piercing bullets improved the effectiveness of the eight machine-guns in the wings of the Spitfire and Hurricane.

Given the resources allocated to Fighter Command it was the most effective system of aerial defence in existence in the world at that time.

It was soon to be tested.

“Contrast this with the state of effectiveness of Bomber Command which the Air Marshals expected to win the war,” said Dr Paton.

“In 1939, British bombers were sent on daylight raids over Germany in the expectation that they could fight their way there and back.

“They suffered horrendous losses.

“Night bombing was the alternative but no provision for this had been made.

“British bombers lacked effective navigation aids to reach the target in the dark or bomb-sights that could enable them to hit it.

“An inquiry in 1941 concluded that few bombs fell within five miles of the selected target.

“The majority of pilots who trained at Montrose were bomber pilots.

“Jock Nicol, Tom Neil’s friend at Montrose, was killed flying a Handley Page Hampden, an aircraft of curious design which hardly had the range to fly to Germany and back.

“PO Freddie Bazelgette of No 8 Course at Montrose was one of many who died flying Fairey Battle light bombers in what amounted to suicide missions, attacking the advancing Germans in France in May 1940.

“Tom Neil was fortunate in being in the minority selected for fighters.

“His own personal experience may have made him feel ill prepared and, as Napoleon observed, ‘No plan of battle long survives contact with the enemy’ but he was joining a fighter squadron flying modern aircraft in a command which was as well prepared for war as was possible with the technology of the time.”

Churchill’s words seem no exaggeration.

“Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.”

Who were the Few and where did they come from?

The vast majority were British and the backbone were career airmen in the RAF.

Others were in the Auxiliary Air Force, formed in 1924, like 603 (City of Edinburgh) Squadron and 602 (City of Glasgow) Squadron.

In addition, there were the University Squadrons established in 1924 and the RAF Volunteer Reserve formed in 1936.

All these were made up of men who learned to fly in their spare time.

There were individuals from most of the Commonwealth countries and from the occupied countries of Europe.

Lastly there were more than 50 naval officer pilots of the Fleet Air Arm serving in RAF Squadrons or in 804 and 808 Naval Air Squadrons.

Altogether there were 55 squadrons organised in four groups operational on July 10 1940.

Dowding had insisted that a minimum number of 50 squadrons would be needed for the defence of Britain and had objected strongly when Churchill wanted to send more fighters to France.

The 55 included two Defiant and six Blenheim squadrons.

The Defiant, a fighter which had no forward firing armament was totally vulnerable to head on attacks and Defiant squadrons had already suffered severe losses.

The Blenheim was a twin-engine aircraft with inadequate armament that was too slow to catch enemy bombers.

In effect, Dowding had 47 effective fighter squadrons.

Dr Paton said it must be remembered that the RAF had lost over 400 fighters in France, Norway and over Dunkirk.

Of these 47, 29 were Hurricane squadrons and 18 Spitfire squadrons.

He said Fighter Command does not seem to have concentrated its Spitfires in the airfields closest to the Channel.

There were more Spitfires in Scotland and northern England than in locations closest to the expected attack.

In the event it did not matter.

Squadrons in the front line did not last long as casualties reduced their effectiveness as fighting units.

Squadrons could be rotated to bring in fresh pilots.

For instance, No 603 (City of Edinburgh) Squadron remained in Scotland until August 27 but was not without combat experience having already shot down 15 enemy aircraft over Scotland.

The squadron was posted to RAF Hornchurch in 11 Group and remained there until December 3.

By that time many of its original volunteer pilots had gone and the squadron had lost much of its original social cohesion.

Only a small proportion of fighter command’s aircraft were in contact with the enemy at any one time and the tactic employed by Dowding and his second-in-command, Air Vice Marshal Park, was to feed relatively small numbers of aircraft into the Battle at any one time.

“No wonder they were called the Few,” remarked Dr Paton who said the Luftwaffe forces facing them across the Channel were very differently organised from the RAF’s functional commands.

Each Luftflotte was a mix of different types of aircraft and its role was primarily to support the army.

Luftflottes 2 and 3 in northern France and Belgium had 18 fighter bases and 17 bomber bases within range of Britain.

On them were based 1,200 bombers, 280 Stuka dive bombers 760 ME 109 fighters, 220 ME 110 twin-engine fighters and 140 reconnaissance aircraft.

Herman Goering, the Luftwaffe’s Commander in Chief, was totally confident that his forces could bring the war to an end without the need for an invasion by the German army by eliminating Fighter Command and forcing the British to surrender or be bombed into oblivion.

The stage was set for the Battle of Britain.

How did it start?

The Battle of Britain started with Luftwaffe attacks on British convoys in the English Channel.

The attacks continued until the British Admiralty was forced to suspend Channel convoys at the end of July.

By that time the RAF had lost 148 aircraft and the Luftwaffe 286.

Dr Paton said it was already clear that the RAF would not be a pushover.

The next stage, began on August 12 with attacks on airfields and radar stations.

A major attack was mounted on August 15, ‘Adlertag’, and by August 18 the Germans had lost another 194 aircraft.

Stage three from August 19 was an all-out effort to destroy Fighter Command by attacking airfields and aircraft factories with bombers heavily escorted by fighters.

These attacks caused serious difficulties for Fighter Command but on September 7 the Luftwaffe changed tactics again and switched to daylight attacks on London.

“It is often said that British bombing attacks on Berlin caused a furious Hitler to demand reprisals but, like many senior officers in the RAF, the Luftwaffe’s leaders believed that bombing would demoralise the civilian population and force the British government to sue for peace,” said Dr Paton.

“At the same time, what was left of Fighter Command would be destroyed as they defended the capital.

“Great damage was done to London and there were many civilian casualties but the Germans lost 200 aircraft and it was clear that Fighter Command was far from defeated.

“On 15th September, what has come to be called Battle of Britain Day, the RAF claimed to have shot down 175 enemy aircraft.

“On September 19th Operation Sealion, the German plan to invade Britain, was postponed.”

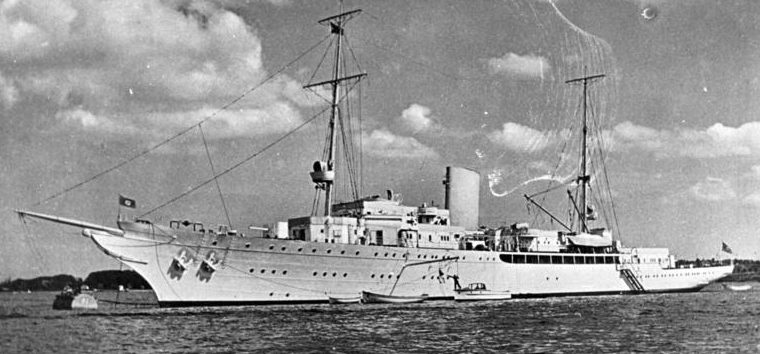

Hitler’s luxury war yacht, the Aviso Grille, which was nicknamed White Swan of the Baltic, was intended to convey Hitler in triumph to London where he would take over Windsor Castle as his home after the planned Nazi conquest of Britain.

Like the British in 1939, the Germans instead resorted to night bombing which continued into 1941.

By then Hitler had turned his attention to the East and began to plan for the invasion of Russia.

Why did the Germans lose the battle?

Dr Paton said it was a lack of understanding which led to poor decisions.

They had overwhelming superiority in aircraft numbers, the Luftwaffe seemed to be invincible and morale was high.

Its pilots were well trained and experienced.

The German Command made the fatal mistake of underestimating and misunderstanding the enemy.

Its leader Herman Goering, a First World War fighter ace, believed he could destroy Fighter Command in a week but he lacked understanding of modern air warfare and this led to poor decisions over strategy and outbursts of fury at his men for his failures.

The fighting soon displayed the Luftwaffe’s weaknesses.

The ME 110 long range fighter was a complete failure against the Hurricane and Spitfire.

The Stuka Squadrons, the elite of the Luftwaffe, had to be withdrawn from the Battle.

The ME 109 was a match for the Spitfire and better than the Hurricane at altitude but it lacked sufficient range and could spend only 10 minutes over London.

The bombers were left with inadequate protection to face the Hurricanes and Spitfires whose numbers did not significantly decease as Goering’s staff predicted.

They grossly underestimated the capacity of the British aircraft industry to replace losses and to repair damaged aircraft.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill made a bold move by making Lord Beaverbook, the press baron, Minister for Aircraft Production.

Beaverbrook ruthlessly cut through RAF bureaucracy and quickly addressed the problems with aircraft production.

The result was a rapid increase in the delivery of new and repaired aircraft to the fighter squadrons.

Soon British factories were producing more aircraft than their German counterparts.

It was the Luftwaffe not the RAF whose numbers of operational aircraft were falling.

The two-way crossing of the English Channel became a daunting prospect for German aircrew and many damaged aircraft did not make it back to France or crash landed with wounded men and aircraft that would never fly again.

The easy victory that Goering had predicted turned into a war of attrition.

The Luftwaffe lost many of its best pilots in the Battle of Britain, dead or shot down and captured.

It never quite regained the heights of morale and effectiveness that it reached in July 1940.

At Montrose a significant change took place soon after Tom Neil’s departure in May 1940 which indicated that the RAF had belatedly recognised that Fighter Command was the priority.

No 8 Flying Training School began to train exclusively fighter pilots.

The venerable bi-planes were replaced with Miles Masters, the first aircraft designed specifically as an advanced fighter trainer for the RAF.

The duration of the training course was reduced so pilots trained at Montrose from June 1940 were available as replacements in the latter stages of the Battle.

Dr Paton said: “Of course, they had flown very few hours in Spitfires or Hurricanes when they first went into action.

“They either learned quickly or died quickly.

“Not everything that British fighter pilots were taught in their training helped towards their survival.

“Tom Neil remarked that flying training had changed little since World War One and the RAF was proud of its close formation flying.

“British squadrons went into battle in 1940 in tight Vee formation and were trained to attack the enemy using carefully orchestrated squadron manoeuvres.

“These tactics may have looked impressive in pre-war airshows but they were not appropriate in 1940.”

The enemy had adopted loose and flexible formations which they had developed in the Spanish Civil War.

Some squadrons had their own tactics.

Tom Neil’s approach was simple: “You dive in, fire off your guns and get out as quickly as possible”.

No 111 Squadron favoured frontal attacks on bomber formations which must have been terrifying for German aircrew, clustered closely in the Perspex nose of their bombers.

It was effective but costly because of collisions.

In October 1940, 111 Squadron was withdrawn from the battle to rest and rebuild in the safety of Montrose.

After only a few peaceful days, German Heinkel bombers from bases in Norway came in low over the sea, attacked the harbour and bombed the airfield and caught the squadron on the ground.

The wooden RAF huts and 1917 hangers burned very well.

The flames could be seen in Arbroath.

Other towns in Angus and Fife were also hit, with bombs dropped on Cellardyke and Arbroath.

What was particularly ironic is that many children from Dundee had been evacuated to Angus towns and villages where they found themselves in greater danger.

Dundee’s worst incident was on November 5 1940 when a stick of four bombs came down on the city in what seemed to be a random attack by a German raider.

One crashed all the way through a four storey tenement in Rosefield Street killing two people and destroying the property and one of the bombs missed the Forest Park Picture House by some 20 yards.

It was packed with children at the time.

The Battle of Britain was the first to be fought over Britain in sight of its inhabitants.

Daily reports on the BBC and newspapers kept the whole population informed.

RAF victories boosted national morale and the numbers of enemy aircraft destroyed made headline news.

On September 15 the RAF claimed to have shot down 185 enemy aircraft.

The real figure was much smaller.

The fighter “aces” who became national heroes included some of the 140 men who trained at Montrose.

Dr Paton highlighted Ian Gleed who trained at Montrose in 1937 and continued to keep in contact with a Montrose family.

He was a career RAF officer and was Flight Commander, flying Hurricanes with 87 Squadron.

He survived the battle but was killed in North Africa in 1942.

Tom Neil also flew Hurricanes with 249 Squadron and later fought in the Battle of Malta.

Dr Paton said Tom Neil’s account of his flying career is one of the best and certainly the most entertaining and he was just as amusing talking about his experiences when he visited Montrose in 2008.

He died aged 98 in 2018.

Most glamorous of all was Paddy Finucane, an Irishman whose ineptitude when doing his flying training at Montrose almost failed the course.

Finucane went on to become one of the youngest Wing Commanders in the RAF.

He died in 1941 returning from a fighter sweep over France when his Spitfire was hit by ground fire and crashed into the English Channel.

What was the legacy of the Battle of Britain?

By the end of October 1940 it was over and it had been a close-run thing.

The Luftwaffe had not been destroyed and continued to bomb British cities for the next few months.

But the Luftwaffe had suffered a severe setback and the losses of some of its most experienced men did permanent damage.

Dr Paton said Britain had showed that the Germans were not invincible, which had important political and psychological consequences at home and abroad.

Churchill’s position as Prime Minister and war leader was now unassailable and there was no more talk of a negotiated peace.

Britain was no longer seen across the Atlantic as a lost cause but a country fighting against tyranny and worthy of support, an unsinkable aircraft carrier when the United States entered the war just over year later.

Had Fighter Command been annihilated, as Goering had confidently expected, Britain would have been defenceless against a ruthless campaign of bombing which must have resulted in surrender.

Thereby he would have proved the theory that air power alone could win a war.

Dr Paton said: “The Battle of Britain is one of the most important battles in modern history and Dowding and Park the only men in history to win a fighter battle.

“How did a proud nation reward the architects of the victory that had saved Britain?

“Dowding was brusquely informed that the RAF had no more employment to offer him.

“Park was relieved of his command and offered Training Command.

“They were the victims of politics in the RAF.

“The bomber men had their revenge and the ambitious Leigh-Mallory who had commanded 12 Group, took over Fighter Command on his way to becoming Air Chief Marshal.

“Churchill did not intervene but he did deliver his famous phrase: ‘Never in the field of human conflict has so much been owed by so many to so few’.”

Five hundred and thirty-seven aircrew of Fighter Command were killed in the Battle of Britain and lie in graves all over Britain.

One hundred and seventy-nine, one third of the total, were classified as having no known grave and their names are remembered on the Runnymede Memorial.

Many of these went missing over the sea.

The remains of men killed in the Battle are still being recovered.

It is difficult to identify them.

PO John Benzie. Winnipeg Canada.

One of The Few.

Failed to return from combat . Age 25.http://t.co/2USnVWPoo6 pic.twitter.com/gezlOvC6Ob— Pippa Ettore (@pettore) December 14, 2014

PO John Benzie, a Canadian who trained at Montrose went missing in Hurricane 2962 of 242 Squadron on September 7 1940.

The skeletal remains of a pilot were discovered in 1976 in the area where Benzie went missing but there was insufficient evidence to meet the strict criteria of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Benzie’s remains lie buried in an unmarked grave at Brookvale Military Cemetery.

He is remembered in Canada where a lake has been named after him.