It was one of the most remarkable achievements in the history of the modern Olympics.

And it featured a teenage Scot with a massive appetite for athletics and the ability to propel herself to record-breaking feats as part of a medal-winning GB relay squad.

Linsey Macdonald, a member of Pitreavie AAC, one of the country’s most go-ahead organisations, may have been diminutive as a child, except when it came to running.

But anybody who thought that she might be frail-looking invariably discovered she was as fragile as a moose.

As she recalled: “From three years old, I ran and I always won. People wanted to give me a head start because I was small, then they would see me run and say, ‘No, it’s OK’.”

When she was 10, her family moved to Dunfermline and the next few years passed in a dramatic flurry of success, superlatives and spiralling media interest.

During the summer, she pushed her body through the wringer on the track in a variety of events, recording noteworthy times in the lot of them. Then in the winter, at just 13, she won the Scottish cross-country championship as if it was a stroll in the park and even the toughest coaches began to recognise she was something special.

Friends and colleagues remember her being superbly disciplined, training six days a week, and blessed with the attitude that genius is an infinite capacity for taking pains.

Her late father, John, was a tremendous influence on her career – and he inspired generations of other stars, both at Pitreavie and in the wider athletic community.

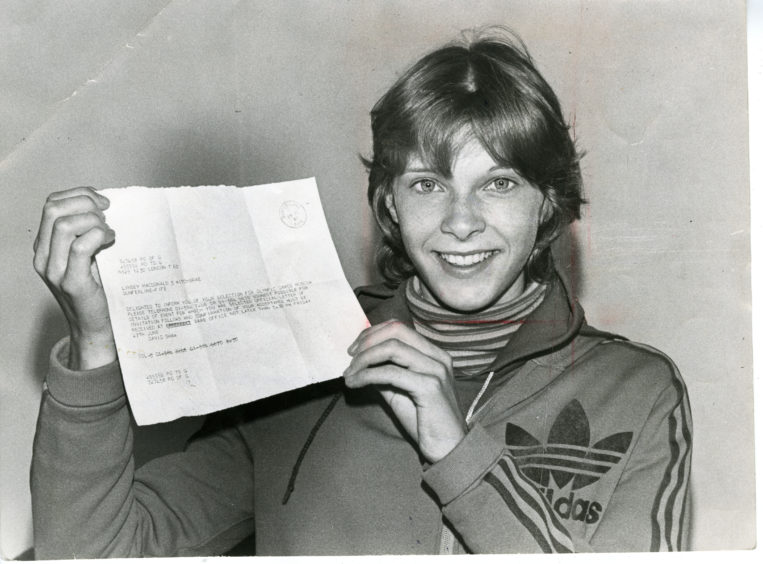

Macdonald’s progress, as she aspired to a place in Team GB for the 1980 Olympics was exemplary. And although there were plenty of reasons to be cynical about those Games – which were blighted by an American boycott and tarnished by drug scandals and suspicions that many hormone monsters went unpunished – Macdonald’s story provided one of the genuinely uplifting moments to savour.

What made her accomplishments all the more extraordinary was the fact that she didn’t even run her first 400m race until she was 15.

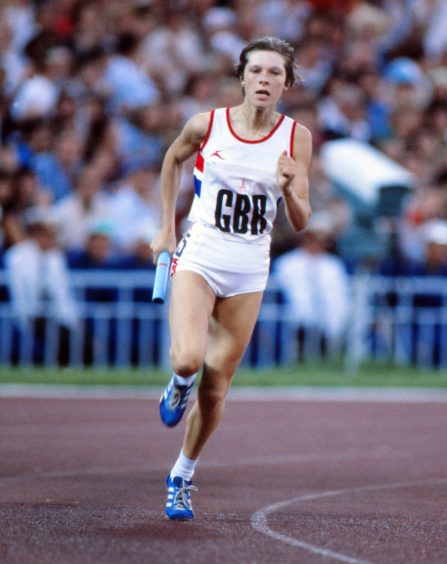

And yet, within the next 12 months, she was representing her country on the global stage, becoming the youngest Briton ever to reach an Olympics sprint final, and the youngest to win a medal – the bronze in the 400m relay.

When you look back at the pictures of her in Moscow in 1980, you can discern she was the baby of the team, just 5ft 3in tall and weighing a mere seven stone.

But she spoke about the three performances which defined her career – the race in which she qualified for the Olympics at Crystal Palace; the day when she broke the senior British 400m record; and then the semi-final in the Olympics; and, of course, the final of the 4x400m relay where she drove a truck through the record books.

She and her teammates, Michelle Scutt, Joslyn Hoyte-Smith and the late Donna Hartley came behind Russia and East Germany in the final, but nothing could detract from the quartet’s unfettered joy when they collected their medals.

Macdonald said later: “You are not just scared that you will let yourself down, you are scared that you will let the team down as well.

“I ran the first leg because that was totally in lane – I was so small and it was so aggressive, it would have been easy for me to be knocked off the track.

“It can be quite lethal at the changeover. But it was just the most amazing feeling – the crowds, the noise, the whole atmosphere inside the stadium.”

Macdonald was pitted against many legendary runners from Eastern Europe, several of whom were widely believed to be using steroids.

The truth about the scale of the abuse gradually emerged in the years ahead – and it wasn’t simply confined to the likes of Russia and East Germany, but cast a cloud over the whole of the Olympics on the track, in the pool and the heavyweights arena and involved competitors in almost every nation, including Britain.

As a teenager, MacDonald was unaware of the enormity of the problem, but as somebody who later studied medicine at Edinburgh University, it soon dawned on her how many records, medals and kudos were being gained through cheating.

However, she recalled of her performances in Moscow: “People joked about the drugs and I joined in, but I didn’t realise what they meant.

“We joked about the women looking like men, and them having muscles in places that we didn’t even have places.

“But I certainly didn’t run with a sense of injustice, because I was just trying to do as well as I could.”

She succeeded in that objective. With a vengeance. In the bigger picture, Allan Wells, Steve Ovett, Sebastian Coe and Daley Thompson might have commanded banner headlines with their gold medals, but there were ample tributes and paeans of praise to the youngster in their midst who was awarded the nickname the Fife Flyer.

She had imagined it would be just be her parents and a few friends in the Kingdom who were watching her heroics at the Olympics, but the size of the audiences swelled as people across the planet sat up and took notice of her feats.

There were people who believed that Macdonald was destined for future greatness in the heady afterglow of her giddy rise to prominence.

They seemed to think that, because she was reaching major finals at such a young age, it was inevitable she would continue improving en route to the top of the podium.

But, as Macdonald developed and moved into her 20s, the injuries and stresses increased and it became more difficult for her to rally from these setbacks. One week, it was tendonitis, the next it was a muscle spasm. And it had a cumulative effect.

In 1981, when the Scot picked up European junior 400m bronze in Utrecht, she was in the same company as future world record breakers including Heike Drechsler and Sabine Rieger, both of whom were subsequently implicated in doping scandals.

Yet, while they kept improving their times and climbed up the rankings – although many of their milestones have now been deleted from the record books – Macdonald was stuck in neutral and eventually heading into reverse gear.

She said later: “Many of these athletes from Eastern Bloc countries were part of a system who did not even know what they were given.

“Many thought they were receiving vitamin supplements. There were so many other aspects at play. I just really loved my time competing. They were still really innocent Games in other respects. Or at least, that is how it felt to me.

“I was just so delighted to be doing something I loved. When you’re actually involved in something, you just feel that it is natural and normal.”

At 18, Macdonald went with the Scottish team to Brisbane for the 1982 Commonwealth Games and once again secured a bronze in the 4x400m relay.

But there were disappointments after that. She was eliminated in the heats of the European Championships in Athens that same year. And she was not in the frame at all for the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles.

Linsey Macdonald in training for the 1980 Olympics in Moscow. Won bronze in the 4×400 relay. pic.twitter.com/M6EEy0DGIG

— PictureThis Scotland (@74frankfurt) April 12, 2019

Ultimately, she never bettered the time of 51.16 she had achieved at 16. But there were still a string of other plaudits to collect on the domestic circuit which she dominated.

Macdonald has no regrets about her success being relatively ephemeral. She relished her time in the spotlight, but she was bright as a button, fascinated by the world of science, engineering and medicine and was determined to pursue an academic path.

Nowadays, she still enjoys putting on her trainers and pounding the streets of Hong Kong when she is allowed a break from looking after her patients. But she is happy in her work, her family life, and strikes one as a truly contented soul.

She said recently: “I still run most days and still love doing it. Sport is a way of life for me. But I hate even to call it running. I really just jog along, most days – not far: three or four miles, something like that. I do a lot of hiking with a jog in it.

“People tend to think, as I did at first, that Hong Kong is an urban jungle, full of buildings, but the majority is trails and trees.

“I can walk and run for hours and not see another person.”

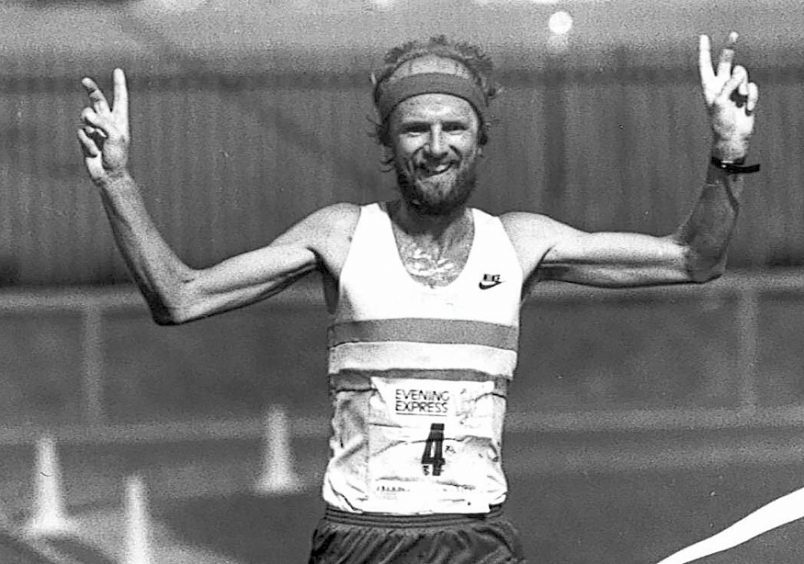

Fraser Clyne recalls Linsey’s remarkable exploits

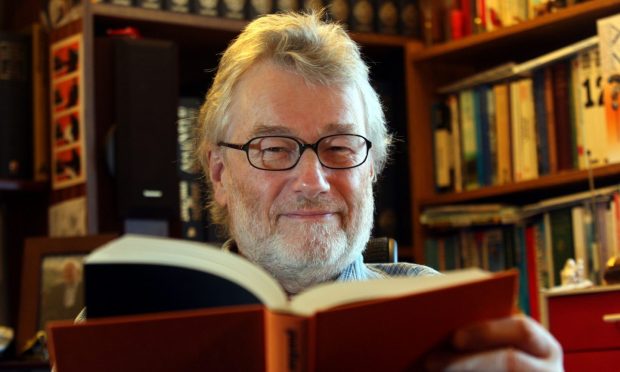

Fraser Clyne represented Scotland on the international athletics stage for many years and now writes about track and field for the Press & Journal.

And he has nothing but admiration for the exploits of Linsey Macdonald in the 1980s.

He said: “I was on the same Scotland team as Linsey on a few occasions, most notably at the 1986 Commonwealth Games.

“However, what amazed me about her was her range of abilities. We both represented Scotland at the 1981 world cross country championships in Madrid.

“She must be the only Olympic sprint medalist to have also competed in a world cross country championships – and she did it just a year later.

“She was such a quiet and unassuming young athlete, but I thought that she produced an amazing performance in Moscow.”