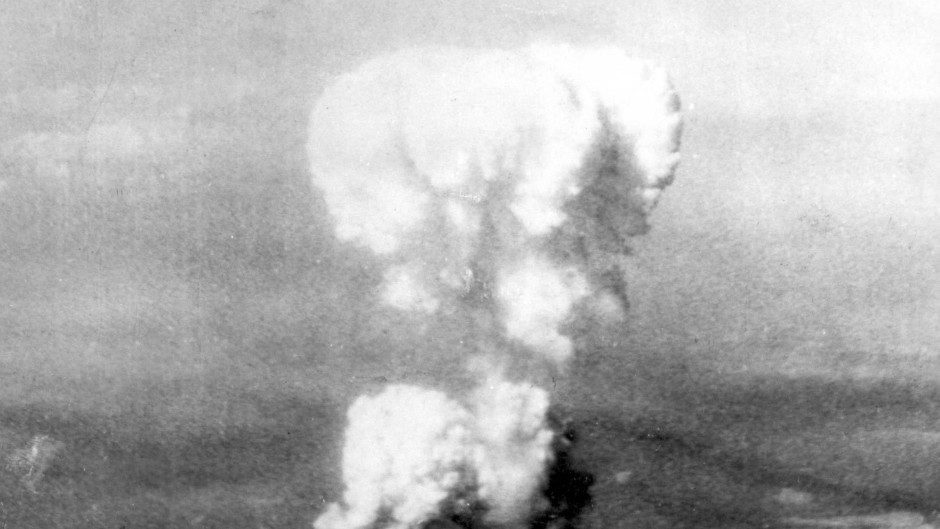

It was one of the most cataclysmic events in world history; the unleashing of the first atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima 75 years ago.

Even now, when the images of the giant mushroom cloud have become seared on our consciousness and we realise that the threat of global annihilation was very real throughout the Cold War and especially during the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, the impact of these weapons which caused massive loss of life and hastened the end of the Second World War arouse strong debate about their use.

The United States made the momentous decision to detonate two nuclear bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9 with the consent of the United Kingdom, as required by the Quebec Agreement.

These killed between 130,000 and 225,000 people, the majority of whom were civilians, and they remain the only uses of nuclear weapons in armed conflict.

In the final year of the war, the Allies had drawn up plans for a very costly and hazardous invasion of the Japanese mainland and this undertaking was preceded by a conventional firebombing campaign on 67 Japanese cities.

The hostilities in Europe had concluded when Germany signed its instrument of surrender on May 8 1945, and the attention switched to the Pacific theatre.

Yet, although the Allies called for the unconditional surrender of the Imperial Japanese armed forces in the Potsdam Declaration on July 26, with the alternative being “prompt and utter destruction”, their ultimatum was ignored, sparking a chain of events which dragged the “genie out of the lamp” three quarters of a century ago.

By the start of August 1945, the Manhattan Project had produced two different types of atomic bombs, and the United States Army Air Forces was equipped with the custom-built Silverplate version of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress which could deliver them from Tinian in the Mariana Islands.

The Allies issued orders for atomic weapons to be used on four Japanese cities on July 25.

And finally, on August 6, one of the modified B-29s dropped a uranium gun-type bomb, nicknamed Little Boy, on Hiroshima.

Another B-29 aircraft inflicted a plutonium implosion bomb, Fat Man, on Nagasaki three days later. These immediately devastated their targets and yet the ominous mushrooms sprouted consequences which lingered for years afterwards.

During the next three months, the acute effects of the atomic bombings killed between 90,000 and 146,000 people in Hiroshima and 39,000 and 80,000 people in Nagasaki; roughly half of the deaths occurred on the first day.

Large numbers of the beleaguered civilian population continued to die for months afterwards from the cumulative effects of burns, radiation sickness, and other injuries, which were compounded by the effects of illness and malnutrition.

Japan eventually surrendered to the Allies on August 15, six days after the Soviet Union’s declaration of war and the bombing of Nagasaki.

Their government signed the instrument of surrender on September 2 in Tokyo Bay, and that action effectively ended the hostilities.

But not before the introduction of a terrifying new force in military combat.

Scholars have extensively studied the effects of the bombings on the social and political character of subsequent world history and there is still heated debate about the ethical and legal justification for the bombings.

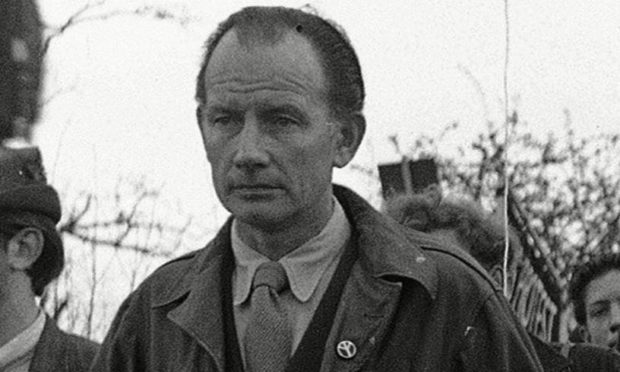

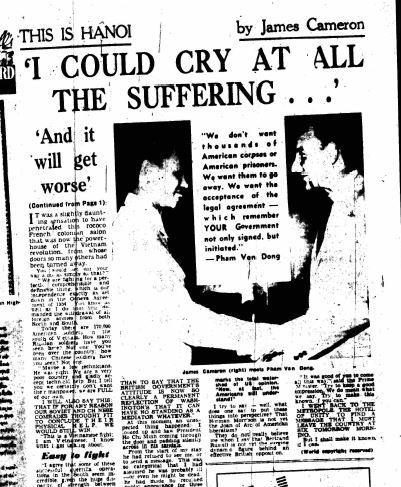

Scottish journalist, James Cameron, who worked at DC Thomson in Dundee for several years, was one of those most affected by being a witness to not one or two, but three different nuclear explosions.

He made no excuses for the atrocities which were committed by the Japanese forces during the war – and repeatedly condemned their decision to ignore the tenets of the Geneva Convention as both “shameful and inhumane”.

But he also believed that the proliferation of increasingly powerful nuclear devices had to be questioned and resisted, which explained his involvement in the creation of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, which rose to prominence in the 1960s.

Mr Cameron, who also worked for Lord Beaverbrook during his distinguished career, was a pacifist, but spent years in dangerous war zones from Korea to Vietnam and Cambodia, never pulled his punches in describing what he witnessed.

And he wasn’t naive about what might have happened if the Nazis had beaten the Allies in bringing the A-bomb to fruition.

He wrote: “If the Russians could have been first with the bomb, they would have been.

“If the British could have been first, they would have been.

“So, indeed, would Hitler, which is not to be thought about. So we can leave the eternal moralities out of this. Unlike most of the current political generation, I have seen some nuclear bombs go off and watched what they did to a city like Hiroshima, a desert like Woomera, an island like Christmas.

“The effect upon me was something I barely understood in the 1940s and 1950s, but which became only too clear as we edged close to destruction at various times.

“Even in the early days of CND, the Bomb was a fact; we did not try to uninvent it.

“We were not in CND to save our own skins. Neither did our campaign denigrate the value and authority of Britain, but strove to increase it.

“A new age arrived in August 1945. We have been living in its shadow ever since.”

The New York Times’ science writer, William Laurence, was one of the few journalists allowed aboard an aircraft which was carrying these original nuclear devices.

He wrote vividly after his experience about the chaos sparked by the weapons.

As he said: “Awe-struck, we watched it shoot upward like a meteor coming from the earth instead of from outer space, becoming ever more alive as it climbed skyward through the white clouds. It was no longer smoke, or dust, or even a cloud of fire.

“It was a living thing, a new species of being, which was born right before our incredulous eyes. In a few seconds, it had freed itself from its gigantic stem and floated upward with tremendous speed, its momentum carrying into the stratosphere to a height of about 60,000 feet.

“As the mushroom floated off into the blue, it changed its shape into a flower-like form, its giant petal curving downward, creamy white outside, rose-coloured inside. It still retained that shape when we last gazed at it from a distance of about 200 miles.”

Not everybody employed such purple prose. Others who were based in and around Hiroshima were horrified at how people were simply atomised in the blast, and Homer Bigart of the New York Herald Tribune, painted an unflinching picture of destruction.

He wrote: “Across the river, there was only flat appalling desolation, the starkness accentuated by bare, blackened tree trunks and the occasional shell of what had once been a reinforced concrete building.”

His compatriot, John Hersey, of the New Yorker magazine, returned to the city a year later and forensically detailed the scenes he encountered and intertwined his account with how it affected six different people in what became a Pulitzer Prize-winning book.

It focused on six Hiroshima survivors: a German Jesuit priest, a widowed seamstress, two doctors, a minister and a young woman who worked in a factory.

One of these, the Methodist minister, Kiyoshi Tanimoto, embarked on an extensive speaking tour throughout the United States and ended up appearing on the popular American TV programme This is Your Life.

He and his family were then introduced to Captain Robert A Lewis – the co-pilot of the Enola Gay which had dropped the bomb on Hiroshima in the first place.

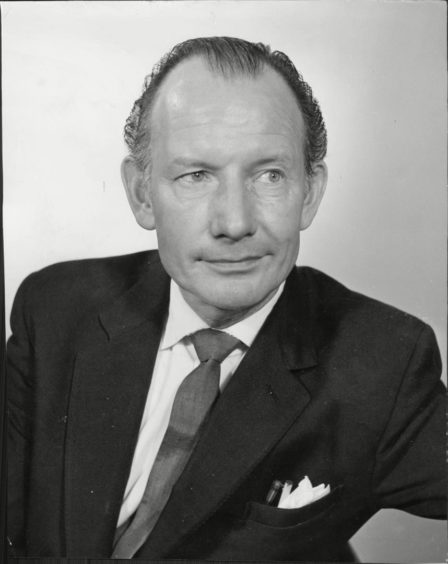

James Cameron, who died in 1985, aged 73, was unequivocal in his feelings towards the birth of the atomic era. But, as he kept insisting, the scientists were not to blame for the terrifying carnage which engulfed Japan and ripped the heart out of two major cities.

As he added, with blackly comic undertones: “I remember General Douglas MacArthur testifying to the US Senate that war should be outlawed and, because the general was a virtuoso and no mean hand at the business himself, it moved many senators to tears.

“But it seems to me they were not too well up on their facts since, legally and officially, war has been outlawed many times.

“It was outlawed in 1919 at the Covenant of the League of Nations. It was outlawed again in the Kellogg-Briand pact of 1928. Then abolished again in the Atlantic Charter of 1941 (during what you might have thought was a pretty drastic war in itself!)

“Finally, we got rid of war for good and all on June 26 1945 – before Hiroshima – in the Charter of the United Nations.

“For half a century, we’ve been outlawing the hell out of war and look where it got us.”

There is an annual James Cameron Memorial Award ceremony in London and the recipients feature many major figures in journalism, including those who have exposed international scandals and previously unreported issues since the late 1980s.

Michael Buerk and John Simpson were presented with the accolade in 1988 and 1990 respectively for their coverage of famine and war.

More recent winners include Fergal Keane, Lindsey Hilsum, John Ware, Gary Younge, Paul Foot, Jeremy Bowen and Lyse Doucet, the latter of whom has won it twice.