A Tayside woman has told how her parents dodged fighter plane bullets and took refuge in storm drains on the way to their wedding when Japan attacked Singapore.

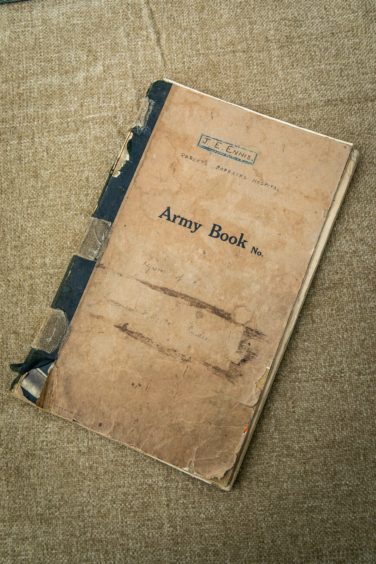

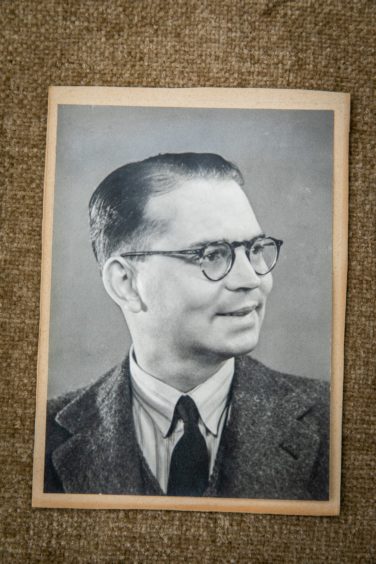

Captain Jack Ennis – an army doctor – and nurse Elizabeth Petrie got married just four days before Britain surrendered Singapore to the Japanese on February 15 1942.

After only a few days, Jack and Elizabeth were interned for the duration of the war.

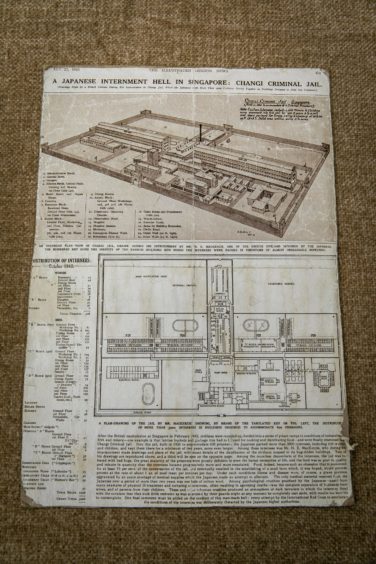

The couple’s daughter Jackie Sutherland from Milnathort has been recalling the incredible events that followed which saw Jack sent to Roberts Barracks with military personnel, whilst Elizabeth, along with some 3,000 civilians, would be ‘housed’ within the bleak cold stone walls of Changi Gaol which was originally built for fewer than 600 prisoners.

The couple were separated and after meeting for 30 minutes at Christmas 1942, they did not see each other again until September 1945.

Jack was born in India in 1911 and qualified as a doctor in London before he returned to British India to set up pathology services in Malaya.

Elizabeth was born in 1912 in Edinburgh where she trained as a nurse in The Deaconess Hospital.

Offered the chance to travel, she took a post as Nanny in the Far East to look after the young children of Rob and Rosamund Scott.

Mr Scott had been posted to the Far East as a rising diplomat.

Jackie said: “In 1941, Rosamund and the children left for Australia and mum returned to nursing in Singapore.

“She was sent to work in a small hospital ‘up-country’ where she met Jack.

“Less than a year later, just four days before Singapore fell, they married.

“Not everyone is machine-gunned on the way to their wedding.

“But my parents were.

“Twice.

“Dodging bullets fired from the attacking fighter plane, they took refuge in the deep storm drains at the side of the road.

“A few days later they were separated to POW internment for the next three and a half years.”

After the surrender of Singapore, thousands of Allied servicemen became prisoners of the Japanese.

They were subjected to a brutal regime of violence, callous neglect and forced labour.

From 1942 prisoners were forced to build the Burma-Thailand railway, which became known as the ‘Death Railway’ for its high mortality rate, among both military prisoners of war, and civilian forced labourers.

For the children, in particular, Changi Gaol was a most sinister place with high concrete walls.

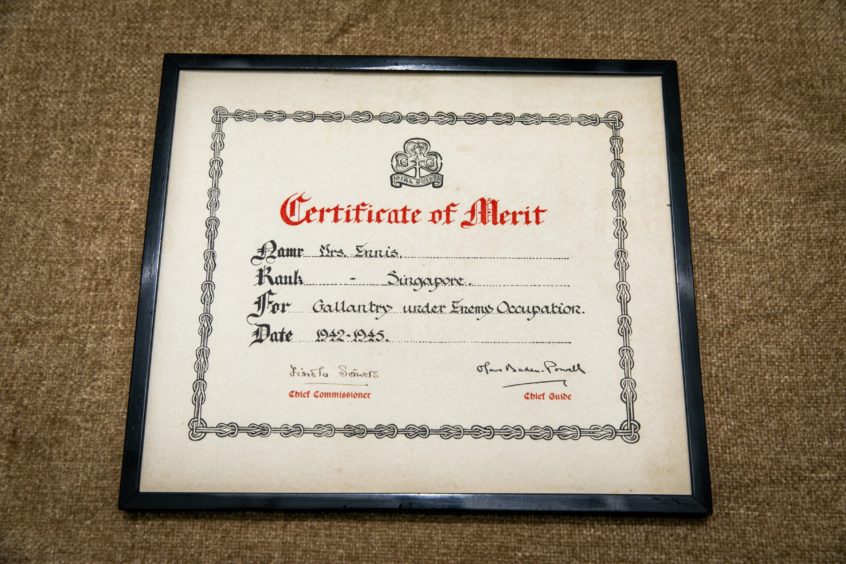

To keep some of the young girls occupied and entertained, Elizabeth set up a Girl Guide company under the strict scrutiny of the guards – with many restrictions, including no saluting, and no National Anthem allowed.

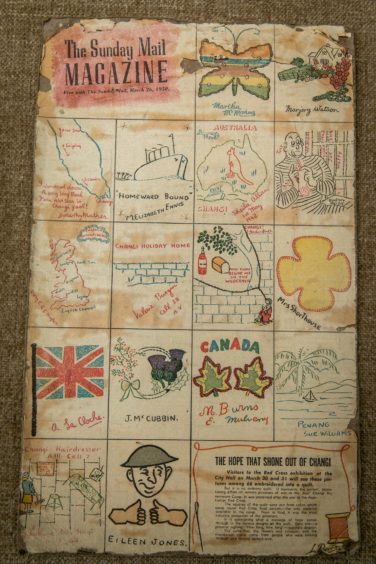

Jackie said: “Begging threads and small pieces of cloth from worn out dresses, sleeves and hems, Elizabeth taught the girls patchwork.

“She was very surprised – and extremely touched – when, on her birthday, a couple of months later, the guides presented her with a patchwork quilt to use in her cell.

“Each guide had embroidered her name in the centre of their ‘rosette’.

“This quilt became the inspiration for the ‘Changi Quilts’, three more patchwork quilts.

“Each six inch square was cut from a rice sack, and then embroidered by a woman in Changi.

“The first completed quilt was presented to the Japanese guards, dedicated to the ‘wounded Nipponese soldiers with our sympathy for their suffering’.

“When the quilt was accepted, the other two quilts were sent to the men’s camp.”

Here, the quilts took on a much more important role, both as a way of getting messages to loved ones in the other camps, and as a show of spirited defiance; the signature on each embroidered patch identified a woman who was alive and well.

For some men, recognising the signature or design was the first confirmation they had had that their wife, sister, mother, relative or friend was alive and interned in the prison.

In 1945, Jack and Elizabeth were reunited and returned to Britain on the SS Monowai, which was the first ship to repatriate into Liverpool.

Post-war, Jack ran pathology services for the Durham Group of hospitals, also taking on forensic work throughout north-east England.

After retirement from the NHS he worked in Australia before finally retiring to Edinburgh.

Elizabeth continued her interest in the Girl Guides, becoming County Commissioner for North-east England.

She died in 2003 aged 93,

Jack died in 2007 aged 96.

They remained close friends with the Scotts.

Rob who was knighted in 1955 and Rosamund were Jackie’s godparents.

Jackie said: “In post-war years, many visitors to our home were also former internees (FEPOW).

“So many in fact, that my younger sister thought everyone’s parents had been imprisoned, just part of growing up.

“They were a close community, even more so as the government of the time discouraged talk of the war in the Far East.

“In May 1945, Britain had come through the highs of VE Day and did not want to be reminded the war had continued until Japan surrendered on the 15th of August 1945.

“As a post-war child, I am exceptionally fortunate that my parents survived captivity. The quilts are now in museums – Imperial War Museum (IWM), Australian War Memorial and Red Cross Headquarters.

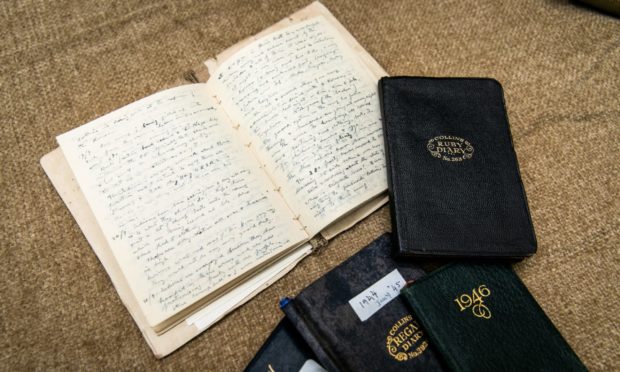

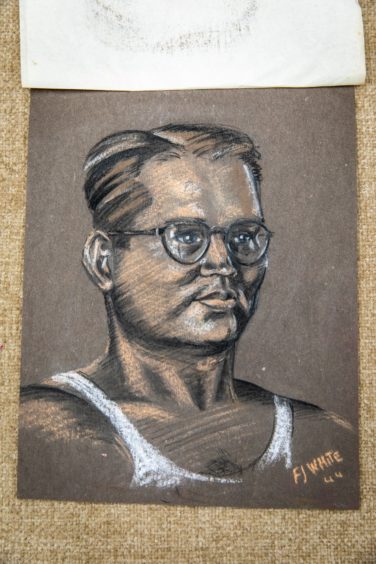

“For my family, we have other precious mementos – amongst them, my father’s wartime diaries, ID cards issued by the Japanese, smuggled notes, original sketches and cartoons, a pair of wooden sandals, and, most touchingly domestic, a pair of bamboo knitting needles from Changi prison.

“I am so pleased that interest in FEPOW continues to rise.

“For relatives, students and researchers, there are now many online resources including CWGC, COFEPOW, IWM, Legion Scotland and Forces War Records.

“As the Scottish coordinator for COFEPOW (Children of Far East Prisoners of War),

“I am happy to help where possible for it is ‘by sharing information and giving it away, that we honour these men and women and they will never be forgotten’.”

Retired army Colonel Andy Middlemiss, who served all over the world in the King’s Own Scottish Borderers for 33 years said: “What an extraordinary, and tough generation our forebears were.

“My father came home only once in six years of war, and that was after being evacuated from Dunkirk.

“My own regiment took terrible casualties in Burma, in the Forgotten Army under the legendary Slim.

“Jackie’s parents embody that extraordinary stoical attitude – waiting three long years to get their married life going again, after so long in Japanese captivity – uncomplainingly.

“Today, some people moan about wearing a face mask in shops.

“The doctor and nurse just gave of themselves for others all those long years in POW camps.

“What a fantastic example they set.

“What great people they were to serve others.

“VJ Day 75 marks the end of six terrible years of suffering and sacrifice on both sides – may we never forget those who died, and served to allow us to be free today.

“Today in the Kohima cemetery, among the 1,378 grave markers, is the famous Kohima Memorial with its historic inscription: ‘When you go home, tell them of us and say, for your tomorrow, we gave our today.'”

Jack’s diaries from Singapore

(The couple first met on June 29 1941)

July 4 1941 – ‘With Elizabeth again this evening, absolutely delightful, both seem to enjoy the jungle, the river, the insect noises – I do believe I am falling in love’.

February 7 1942 – ‘Day opened peacefully enough. Dive bombing on P. Ubin as usual. About 1.45 p.m. at lunch 27 (fighter planes) went over and loosed about 100 bombs. All round mess, floor heaved like mad. Hell. T block hit above my Lab, many injured and killed.

Dead and dying all over operating theatre floor, the surgeons tried hard to get on with their job, dhobis, water carriers, naik killed.

(Nursing) Sisters stood it well.’

February 11 1942 – ‘Sisters evacuated. Elizabeth doesn’t go.

Elizabeth and I are to be MARRIED. Special licence from Colonial Secretary and Sir Shenton. Risk bombs and shells. On the way Elizabeth and I machine gunned at Gillman, twice in big air raids.

The deed done by Mrs North-Hunt, Registrar General here.

Left Elizabeth at 20 C.G.H. (Changi General Hospital), to Tyersall – the Awful Fire. Burned to the ground, everything gone, about 170 patients, all bad cases as well

It was awful, every hut gone, my truck, one GP left. Still shelling when I got there.

My first night back with darling Elizabeth.’

March 2 1942 – ‘Elizabeth and I slept in Room 21, The Club, – too many bugs and mosquitoes for comfort. Our last night – for how long? All packed to go. Awful sick feeling.

A very brief farewell outside Whiteways, too sudden in fact to leave my darling wife behind. Away about 1.30 p.m. by car at head of convoy of 11 trucks. Japs somewhat difficult near jail, allow us through after parley. Big parade at Changi for Jap inspection, what a collection of British troops.

Sleep on my stretcher.’

March 20 1942 – ‘Spent some of the day in work and made an effort at repairing the salvaged chair.

Beginning to despair a little thinking of Elizabeth and Mother all day. Feel awfully hungry as does everybody else before meals – blasted rice.

Also getting a trifle weak, otherwise well and thank goodness there is enough of work to keep me occupied.

Dysentery and flies still up. More cases of ankle oedema are appearing daily.

Malaria about the same.

A long think about Elizabeth tonight – how I long for my darling.’

May 17 1942 – ‘Bloom is the happiest man in the camp; he’s had a long note from his wife, mention of Elizabeth in it to say she’s well. Made me feel awfully jealous, wonder why my darling couldn’t get a note to me?’

July 1 1942 – ‘Visited Southern Area and looked at more lists of internees names, Elizabeth’s was still absent, walked back awfully fed up. But – joy of joys, there was a note from my darling on my table. I delayed to open it, did everything else first, then sat down to a first read of it. Wonder which of my letters she has received, can’t quite make out. Hers must have been dated about 28th. Bloom got one too and so did the others. Oh I feel good, Elizabeth, must thank you quickly for this.’

December 25 1942 – ‘Shortest half hour of my life

Woke very early, much singing all over of carols, we even heard a band on the hill above us. We assemble at Office at 10.0 a.m. for the ambulance, it fetched civilians looking very ill, then the journey down. We hung about for 11/2 hrs, 26 in all, we checked and re-checked then marched to south wall of ‘H.M. Prison 1936’ where we met again MY OWN DARLING – what a sensation! 12.30 – 1pm and it’s all over and finished until when??’

July 25 1945 – ‘There are more skeletons walking around the camp than ever before, and others, just lying on their beds from one scant meal to the next – rations are very low.

Everybody is very optimistic, though if we are not relieved or killed in a few months, death will come on a great percentage anyway. Extra food for the worst is almost exhausted now and our medicines are again very low.’

August 15 1945 – ‘The Emperor broadcast that they had surrendered at 1200 hrs today, but at 1400 hrs the air raid sirens went here in Singapore and fighter planes went up as usual.’

September 5 1945 – ‘At last I see Elizabeth again – but what a short time, three hours, and I was rushed from one place to another to see Hugh and Rob (Scott) and all the others – but I only wanted to see you, darling. Am I jealous?’

September 11 1945 – ‘Left Kranji at 0700 hrs., aboard SS Monowai by 0900 hrs. E came aboard little later.

Impressions – small vessel 11000 tons, 1189 aboard, about 800 P.O.W. and internees from Sime Road camp. On S.M.O. instructions we are on very little to eat, very, very hungry first day. Ship, or its M.O. have no idea as to our health state. Water shortage aboard. Very crowded, 16 to a cabin is usual, very hot and stuffy. No cold drinks or water available to satisfy our craving. No deck space, no deck chairs, no cosy corners.

Elizabeth, as usual, is awfully cheerful about it all.

Sailed at 1300 hrs.’