It was the night when Scottish football was engulfed in a vale of tears; an occasion when delight and relief at a positive result were replaced by laments for the loss of one of the greatest figures in the game’s history.

Even now, 35 years after the death of Jock Stein at the end of his country’s World Cup qualifying match against Wales in Cardiff, there’s still a numbness and tristesse at the manner in which he was snatched away from his family at just 62.

It an instant, sport was put in perspective by the sight of players weeping as if they had lost their father.

In one or two cases, that probably wasn’t that wide of the mark.

As somebody who had steered Celtic to their European Cup triumph in 1967, orchestrated the club’s nine-in-a-row haul of domestic championship titles and replaced the hapless Ally MacLeod after the embarrassment of Scotland’s 1978 World Cup campaign, Stein had established a global reputation throughout the sport.

He was tough, he was uncompromising and when he joined forces with the younger Alex Ferguson to help their compatriots through a difficult qualifying group, it seemed like a marriage made in heaven.

Only they and other members of the backroom staff were privy to the pressures which were taking their toll on this redoubtable Scot.

By the time that he and his squad travelled to the Principality early in September 1985, they were facing a difficult task against quality opponents, who had already beaten them at Hampden Park.

The equation seemed straightforward: if the Welsh, managed by Mike England, won again, they would be through to a play-off against Australia.

The Scots, in contrast only needed a draw to secure the latter.

But, on an evening when the wheels regularly threatened to fall off, when the visitors fell behind to a Mark Hughes goal and with the home supporters at the height of their choral powers, every twist and turn seemed to bring fresh anxiety for Stein and his team, on and off the pitch.

It was at the interval, with recriminations mounting among the Caledonian contingent, that the scale of the tensions became all too apparent.

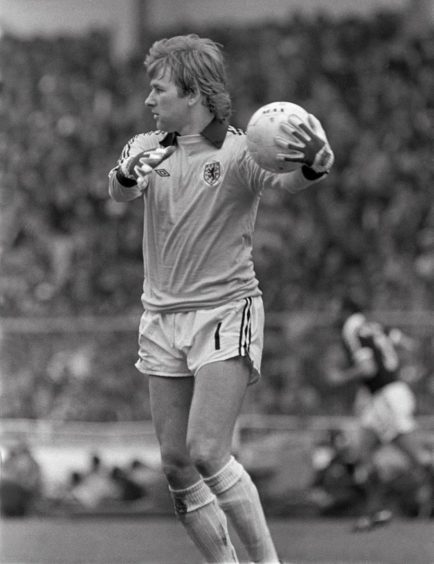

Alan Rough, the veteran goalkeeper, who had already appeared at two World Cups, was called into the ranks as cover for Jim Leighton, but nobody, least of all Rough himself, expected he would be summoned into the action.

In fact, even as the Welsh Dragoon Guards were regaling the audience with a half-time selection of standards, he and David Speedie decided to “have a carry-on, kicking a ball over the musicians’ heads and trying to skelp them on their bearskins”.

Their jolly japes were abruptly curtailed when the Scotland physio, Brian Scott, marched up to Rough and told him to get ready to play in the second half. And that was the prelude to the normally genial goalie walking into the middle of a stramash in the dressing room.

He recalled: “When I entered, it was pandemonium. There were teacups splattering off the walls and Jock and Alex were screaming at each other in the toilet area.

“Jock was shouting: ‘You never told me that Jim wore f***ing contact lenses’.

“And Alex responded: ‘That’s because I never f***ing knew it myself’.

“The veins on the temples of both men were absolutely bulging. This was football at its most ferocious and I think if any of us had gone near either of them, we would have been thrown in the lavatory.

“The place was like a boxing ring. You could cut the atmosphere with a knife and I remember asking myself: ‘What the hell am I letting myself in for here?’ But eventually, Jock walked towards me and said just three words. Two of them were ‘You’re on!’ And I was.”

Stein had been hampered by injuries to key players ahead of the Ninian Park clash and was deprived of the services of such gifted performers as Kenny Dalglish, Graeme Souness, Alan Hansen and Steve Archibald. Despite his notable achievements, Scotland has failed to reach the 1980 and 1984 European Championships and limped out of the World Cup in 1982.

None of this helped Stein’s mood, but he was also taking heart medication and, even with Ferguson at his side, the strains were wearing away at him behind the scenes.

It must have been a tremendous shock to him to discover that Leighton hadn’t brought spare contact lenses down to Wales with him (and it was even a surprise to the goalkeeper’s Aberdeen manager, Ferguson).

But the events during the next 45 minutes will never be forgotten by anybody with even a passing interest in football lore.

For his part, Rough was relaxed and played with a confidence which sprung from his lack of time to fret.

The tide began to turn in the Scots’ favour, but they were still trailing when Stein made what turned out to be his climactic decision as manager, replacing Gordon Strachan with Davie Cooper.

However, as Rough recalled: “The next half-an-hour is forever etched in my mind. There was the surge of joy when a shot from Speedie struck David Phillips on the arm and the Dutch referee Jan Keizer, awarded a penalty, which was converted by Cooper.

“But then, there was confusion when we noticed some kind of commotion in the Scotland dug-out and the realisation that what I thought might be an outbreak of crowd trouble was something worse for any of us who loved Jock Stein.

“At the end of the game, a 1-1 draw, we were all jumping up and down, with sheer relief as much as elation, in the dressing room when Alex came in. He looked ghastly and said: ‘Look lads, there is no easy way to tell you this, but Jock has had a heart attack and we are trying to find out how he is’.

“We all just shut up. We were all devastated and nobody knew what to do. Nobody said a word, even while officials milled back and forwards, and we shed tears.

“Then eventually, following what seemed like an eternity, the news filtered through that he had died. It was awful. And it was the most sombre, depressed group of young men you could ever have encountered as we later made the journey to Cardiff Airport, shrouded in grief.”

In essence, football had been put in its place. Not a matter of life or death, not an excuse for fan violence, just a game to be enjoyed with a proper perspective.

But as Strachan, Rough and their colleagues later stated, if there were any celebrations among the Tartan Army, it could only have been because they didn’t know what had happened.

There can’t have been another occasion in Scottish football, when a triumph of sorts, was so completely overshadowed by tragedy.

Mike England, to his credit, spoke emotionally and passionately about his overwhelming sadness, not at the result which had been reduced almost to an irrelevance, but at the loss of a giant among men, a genuine hero.

Team captain Willie Miller said simply: “The whole team are shattered. The game really means nothing to us now.”

Cooper, who had notched the penalty which rescued matters for the Scots, was equally disconsolate in the aftermath, adding: “We couldn’t believe it at first. We thought we had pulled things back for the gaffer, but everything is ruined now.”

And yet, according to Rough, there had been indications that the proud man Stein was in poor health even in the build-up to the contest.

He declared: “The burden placed on Jock must have taken its toll. It would have been more surprising if it hadn’t. He had recovered from a car crash, and he had walked away from Celtic with a dignity which would have been beyond the majority of us.

“Looking back on it now, as we prepared for the match, Jock didn’t appear well. He slouched around the team hotel in Bristol, which wasn’t his normal demeanour. He usually loved his food, but people noticed that he would just nibble at his plate. He was surviving on morsels and his brow seemed constantly furrowed.

“At the time, we just dismissed these things as evidence that even Jock, one of the legendary managers, could fall prey to anxiety and tension.

“But, there again, I told him I had staved three fingers while playing for Hibs against Celtic on the previous Saturday. In previous times, this might have led to him blowing a gasket or even sending me home.

“But he just glanced at me with a weary expression and said: ‘It’s okay, you won’t be needed’. Suddenly, from being a masterful presence, somebody who could inspire admiration and fear among the most battle-hardened veterans, he looked old and grey.”

After a forest of trees had been used to compose suitable tributes and obituaries, Stein’s funeral took place in Glasgow on September 13 and, understandably, it was a lachrymose occasion, attended by people who could barely believe he was gone.

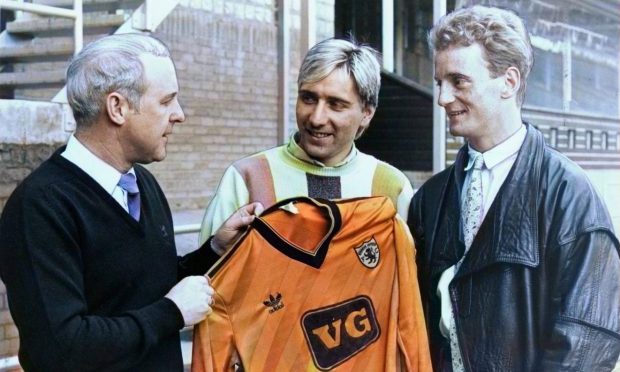

His lieutenant, Ferguson, took over and led the Scots through their potentially tricky two-leg play-off encounter with the Australians.

The Aberdeen boss, a famously volatile and fiercely competitive character, whether in football, political debates or quizzes on flights to international games, was uncharacteristically calm and restrained after picking up the torch from his mentor.

Nobody was in the mood for picking fights.

As Rough recalled: “There was an undercurrent of sadness among the squad and Alex and his coaching staff, which included Walter Smith, Archie Knox, Andy Roxburgh and Craig Brown.

“We won the game at Hampden 2-0 with goals from Cooper and Frank McAvennie (and drew the second match Down Under 0-0 in sweltering heat with Leighton producing an imperious display), but this wasn’t a normal international and it would be crazy to pretend otherwise.

“On the contrary, in the days leading up to the first leg, the conversations kept returning to anecdotes about Big Jock and how he had been such a massive figure in our football.

“I saw how much the Scotland job meant to him. On one trip abroad, he spotted a group of Scotland fans and turned to me and said: ‘You know, Alan, these are the folk who really matter, the lads who shell out hundreds of pounds to support this team and expect nothing more of us than we offer them all the courage and commitment that we can.

“It may be that we are never going to win the World Cup, but these supporters believe in us and they think we can. And there are thousands of them who would love the chance to pull on a Scotland shirt even once in their lives. Always be proud to wear the jersey’.”

Jock Stein, the former miner from a working-class background, would probably have been abashed at the extravagant paeans of praise which were penned and broadcast in his honour after that fateful evening in September in Cardiff.

But he deserved them all.