Skye was the setting for a visit from one of the most famous authors in the history of literature 90 years ago this summer.

But the subsequent intrigue and mystery which surrounded the marriage of Agatha Christie and Max Mallowan in Edinburgh on September 11 1930 was sufficient to tax the little grey cells of Hercule Poirot.

Christie, who had endured a feverish interest in her activities after she went missing in the north of England for 11 days in 1926, was suspicious of the media for the rest of her life and wanted to avoid any publicity as she prepared to tie the knot for the second time.

Yet, in travelling to Scotland and planning for the ceremony with methodical precision, she not only glossed over the precise details of where the church service actually took place, but changed her age and that of her husband-to-be.

Even then, she agonised over whether she should marry somebody who was 13 years her junior.

The mystery of Agatha Christie’s wedding

Christie created some of the best-selling novels in the entire history of literature including Murder on the Orient Express, And Then There Were None, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd and Death on the Nile – and she comes third in the global popularity stakes behind the Bible and William Shakespeare – but she only briefly alluded to the wedding in her autobiography, which was eventually published after her death in 1976 at the age of 85.

She wrote: “I had had so much publicity and been caused so much misery by it that I wanted things kept as quiet as possible.

“We agreed that (her friends) Carlo and Mary Fisher, and (her daughter) Rosalind and I should go to Skye and spend three weeks there.

“Our marriage banns could be called there and we would be married quietly in St Columbia’s Church in Edinburgh.

“I found Skye lovely, I did sometimes wish it wouldn’t rain every day, though it was only a fine, misty rain which did not really count.

“We walked miles over the moor and the heather and there was a lovely soft earthy smell with a tang of peat in it.

“The days passed in Skye, my banns were duly read in church, and all the old ladies sitting round beamed on me with the kindly pleasure that all old ladies take in something romantic.”

These words gloss over some awkward details, such as the fact that the ceremony actually took place not in St Columba’s, but St Cuthbert’s, the picturesque little church which has become a favoured place for Christie aficionados, many of whom have become accustomed to dressing up as Poirot or Marple and visiting various sites across Britain.

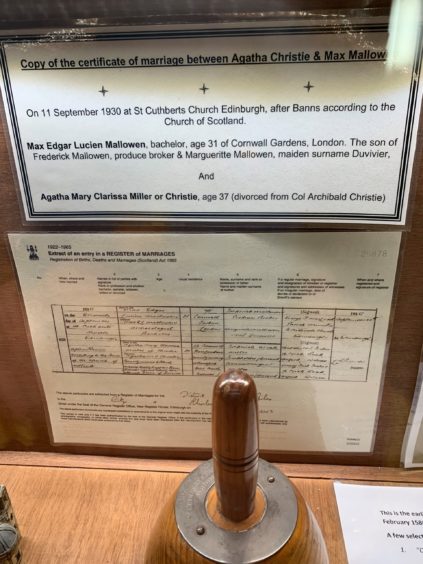

Inside the building, there is a small shrine to the couple and a copy of the marriage certificate. This declares: “On 11 September 1930, at St Cuthbert’s Church, Edinburgh, after Banns according to the Church on Scotland, (the marriage took place of) Max Edgar Lucien Mallowan, bachelor, age 31, of Cornwall Gardens, London. The son of Frederick Mallowan, produce broker and Margueritte Mallowan, maiden surname Duvivier and Agatha Mary Clarissa Miller or Christie, age 37 (divorced from Col Archibald Christie).”

However, by September 11 1930, Christie, who was born in Torquay on September 15 1890, was just a few days away from turning 40.

Mallowan, for his part, was born in London on May 6 1904 and was just 26 – considerably younger than the age of 31 which is conveyed in the official marriage record.

And the decision to change these ages came directly from Christie’s reservations about marrying again after the traumatic breakdown of her relationship with her previous husband.

She said: “I was so miserable, so uncertain, so confused. First, I decided that the last thing I wanted to do was marry again, that I must be safe, safe from ever being hurt again; and that nothing could be more stupid than to marry a man many years younger than myself.

“Then, imperceptibly, I found my arguments changing. It was true that he was much younger than I was, but we had so much in common. He was not fond of parties or a keen dancer; to keep up with a young man like that would have been very difficult for me.

“But surely, I could walk around museums as well as anyone and probably with more interest and intelligence than a younger woman.

“I could go around all the churches in Aleppo and enjoy it; I could listen to Max talking about the classics, could learn the Greek alphabet and read translations of the Aeneid.

“In fact, I could take far more interest in Max’s archaeological work and his ideas than in any of (her first husband) Archie’s deals in the City.”

Keeping the secret

Christie spoke to countless friends and relatives, asked for their opinions and heard both sides of the argument before deciding to take the plunge.

However, she was determined not to highlight her intentions to anybody outwith her immediate circle. By 1930, she had established herself as a publishing phenomenon, but could not bear the notion that the newspapers would unearth her secret.

Hence her choice of Skye as the ideal place to spend a few weeks while Mallowan remained in London and prepared the groundwork for a trek to northern Iraq a few months later.

If this sounds unconventional, that’s because she always lived on her own terms. But there was also a sense of Christie arranging the wedding like the plot of one of her own books.

As Rev Peter Sutton, the current minister at St Cuthbert’s, told me: “It might seem peculiar that she served the banns so far away from where she lived or where she was being married.

“And I am surprised that she gave different ages for herself and her husband-to-be, since these details usually have to be confirmed with the registrar before the wedding proceeds.

“But, in many ways, I think she was covering her tracks and she was doing her best to stay one step ahead of everybody else.

“She was very famous at that time and, even now, her works have remained remarkably popular and I know that people have travelled to Edinburgh just to visit the church and take a look at her wedding certificate.”

As the ceremony approached, the secrecy was maintained by Christie and her close friends. And if the author had feared there might be any invasion of her privacy, all the clandestine arrangements reaped a positive denouement.

A ‘triumphant’ marriage

Not even the most tenacious investigative journalist had a clue it was happening. Her Skye vocation and serving of the banns on Broadford went unnoticed.

The biggest threat she faced was from the midges during her three-week stay on the island.

She later wrote: “Max came up to Edinburgh and Rosalind and I and Carlo and Mary came over from Skye.

“We were married in the small chapel of St Columba’s [sic]. Our wedding was quite a triumph – there were no reporters there and no hint the secret had leaked out.

“Our duplicity continued, because we parted, like the old dong, at the church door. Max went back to London to finish his [archaeological] work on Ur for another three days, while I returned the next day with Rosalind to Cresswell Place [in London].”

She continued: “Max kept away, then two days later, drove up to the door in a hired Daimler. We drove off to Dover and thence crossed the Channel to the first stopping place of our honeymoon, which was Venice.

“Max had planned the honeymoon entirely himself: it was going to be a surprise. I am sure that nobody enjoyed a honeymoon better than we did.

“There was only one jarring spot on it and that was on the Orient Express which, even in its early stages, was once again plagued by the emergence of bed bugs from the woodwork.”

The whole occasion may have been staged with a host of red herrings, and the couple might have been economical with the truth about their ages.

But they were very happy together and were subsequently together for the next 46 years.

Indeed, Christie joked about how she had forged an alliance with somebody who had the ideal vocation.

As she said: “The good thing about being married to an archaeologist is that the older you get, the more interested he becomes.”

Solving crimes on Skye

Andrew Wilson has created a series of novels featuring Agatha Christie, not as a writer, but a crime-solving sleuth.

And his latest book I Saw Him Die entails the famous author journeying to Skye where she is tasked with unravelling a particularly knotty case, involving a claustrophobic country house, nursery rhyme clues and poison.

The title alludes to the ominous verse: “Who saw him die? I, said the fly, with my little eye. I saw him die.”

Wilson, who has also written biographies of Patricia Highsmith and Sylvia Plath, is among those who believe that Christie should be regarded as more than just a producer of fluffy puzzles and parlour games.

After all, there was a morbid streak to much of her output, which was hardly surprising, given how she witnessed the horrors of the First World War, acquired a detailed knowledge of poisons, lost her father when she was just 11, and became the subject of global media speculation after she abandoned her car at an English beauty spot and vanished for more than a week before being found in Harrogate in 1926.

As he said: “She presented herself as a polite, upper-class lady to the world, but it was a disguise. Beneath that, there was something much more complex and interesting going on.

“There is this perception of her as a cosy figure – a bit like her own Miss Marple – but she had a sharp brain and a cynical view of human nature.

“After all, to have written the incredibly dark plots of Crooked House or And Then There Were None makes Christie much more interesting than the perception of her stories being some kind of Cluedo game where you just have to solve puzzles. That has always fascinated me.”

I Saw Him Die is published by Simon & Schuster.

Agatha Christie’s work still shines on stage and screen

It’s the centenary of the publication of Agatha Christie’s first detective novel.

She began writing fiction while she was working as a nurse during the First World War, which she later described as offering her a pathway between adolescence and adulthood.

She began her debut novel The Mysterious Affair at Styles in 1916 and, although she had to be patient before it came to fruition, it was eventually published in 1920.

The story focused on the murder of a wealthy heiress and introduced readers to Christie’s most famous character – Belgian detective Hercule Poirot.

Even now, a century later, the little sleuth is one of literature’s most enduring creations, both in print and on the silver screen.

Christie herself was no great fan of the character, just as Arthur Conan Doyle gradually grew weary of Sherlock Holmes, but they have both developed a life of their own.

Indeed, on October 9, there will be the release of a big-budget new film adaptation of Death on the Nile, directed by and starring Sir Kenneth Branagh, alongside Gal Gadot, Annette Bening, Dawn French, Jennifer Saunders, Tom Bateman, Armie Hammer and Letitia Wright.

It also features north-east luminary Rose Leslie, who previously gained prominence for her leading roles in Downton Abbey and Game of Thrones.

More than 40 years after Christie’s death, her star is still in the ascendancy.