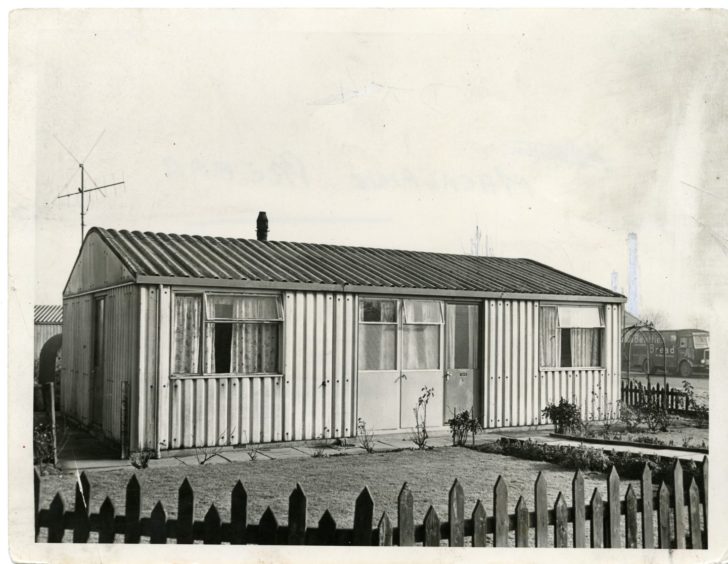

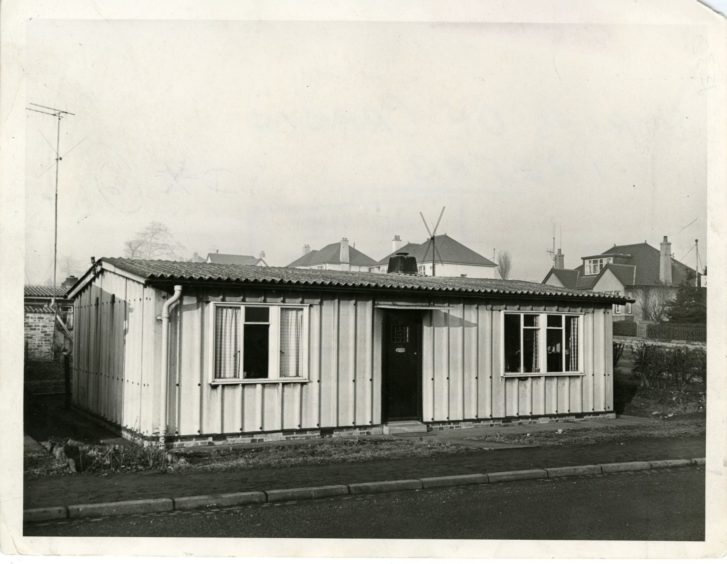

They were the “rabbit hutches” which sprung up across Tayside and Fife following the Second World War.

The combined impact of war and lack of commercial high street activity meant there was a severe shortage of money and materials to cope with housing demand in the late 1940s.

Such was the extent of the problem that squatters had occupied the 100-room jute baron’s mansion of Castleroy in Broughty Ferry in August 1946.

In a speech in March 1944, Prime Minister Winston Churchill promised 500,000 temporary new homes to deal with the housing shortage.

The government delegated powers to local authorities to acquire land, prepare the sites and install the infrastructure, roads and utilities.

Local authorities applied for the number of prefabs they needed and Dundee Corporation erected 1,500 of these buildings between 1945 and 1949.

Four different designs were used in Dundee.

The first to be erected was the Phoenix type at Strips of Craigie in August 1945, the first of 93 to be built in the city.

The most abundant type was the Arcon design.

There were 791 of them in locations such as Craigiebank, Glamis Road, Linlathen and Kingsway.

Next in number was the aluminium type and 546 were erected with Blackshade and Craigie Drive among the sites.

The fourth prefab type was called the Tarran and among locations for the 120 of them was Barnhill where some of the first were unveiled in July 1946.

Prefabs were prioritised for returning service personnel and their families and people who had been bombed out of their homes and those who were living in overcrowded, insanitary conditions.

Fittingly the first house available for occupation in Strips of Craigie in 1945 went to a war-wounded veteran who had been taken prisoner at St Valery in 1940.

Although small and unassuming in sight, for many it was the first time they could boast of having a space of their own after the deprivations of the war years.

Nearly all shared a common problem with dampness, due to condensation, and, gradually, whole schemes were earmarked for demolition to make way for “superior” housing.

They started to disappear gradually, making way for newer dwellings in the 1960s.

In Perth for example, a typical area where prefabs made way for a block of flats in the early 1960s was Potterhill, the grounds of an old estate opposite the city centre on the east bank of the Tay.

Notice to quit

Only 90 were left in Dundee by 1970 when notices to quit were sent to all the remaining tenants of the homes.

Some managed to stay and turned down the offer of a shiny new home and today there are just a handful of original prefabs still standing.

Jane Hearn, the curator of the Prefab Museum, said 156,623 temporary prefabricated bungalows were produced in Britain under the 1944 Temporary Housing Programme.

“I often say about prefabs that ordinary people were given something good for a change,” she said.

“There was a lot of care taken between the Ministry of Works and the Ministry of Health to provide modern fittings, hygienic kitchen storage, ease of cleaning, lots of light through big windows and enough space all round.

“The first tenants of the prefabs were young couples with one or two children, around the same age and from similar backgrounds.

“The big gardens enabled them to supplement their diet with home grown vegetables and fruit while rationing was still on, and provided a safe place for their children to play.

“People have told me it was like a dream come true to have an indoor toilet and bathroom, and a proper modern kitchen, and not to have to share the home with in-laws or others.

“Where there was sufficient space to erect a reasonable number of prefabs, there were recommended layouts often around a little green.

“You will see from an old map of the prefabs off Greendykes Road that there was a little crescent, alleys between the prefabs and some had huge gardens.

“The government was keen to promote commonality and these factors together contributed to a strong sense of community and neighbourliness, and friendships were forged between tenants and their children.

“I am not sure if it was widespread practice but I was told by some tenants they were asked to sign a form that they would move out after ten years which was the length of time the prefabs were supported by the government.

“While a small proportion of prefabs were dismantled within this time frame others stayed up 10, 20, 30 or more years, by which time they could no longer be considered temporary but people’s homes.

“The design of the prefab meant it could become a lifetime home that people could grow old in with few adaptations, was easy to manage and they often knew existing neighbours.

“The bungalow frequently comes top in a poll of homes people would most like to live in.”

Camaraderie

Despite their basic nature, prefabricated houses tended to inspire affection among their inhabitants and it is said that the camaraderie was second to none.

Among the husbands there was a great swapping of mowers, graips and garden-know-how.

Wives borrowed sugar and children swapped E4 and D2 sweetie coupons.

Local historian Dr Norman Watson said: “Modern society may scorn that sort of society if not its good neighbourliness, but there is little doubt that life in prefabs had traits not evident in the towering blocks and sprawling inner city schemes that succeeded them.

“And despite that 10-year life span, and the fact that the last of them were expected to be pulled down 50 years ago, many are still going strong – the survivors of an era in which tenants were happy and loathe to leave their marvels of compactness for a shiny new flat.”

Wildlife expert Jim Crumley: The very word prehab for me is synonymous with ‘home’

Number 97 Glamis Road cradled the first 13 years of my life, and I have been homesick for it ever since.

It had a scent: a blend of coal fires and linoleum, of breakfast porridge, lunchtime stews (lunch was called dinner and the concept of dinner in the evening was incomprehensible – we ate “tea” at 5 o’clock), afternoon baking, and on winter evenings the added frisson of an Aladdin paraffin stove in the lobby.

It was a winter icebox but in summers we lived as much outside it as in, and our garden was scented by phlox, carnations, rambling roses, and instilled in me a lifelong affection for lupins.

Decades after we left, I did some work in Alaska where (among countless natural wonders up to and including grizzly bears and humpback whales almost within touching distance) I encountered miles of wild lupins along roadside verges, and among so much natural splendour, a vision of the prefab briefly crowded out all of it.

Genius

The design was a work of genius.

Into a corrugated, off-white box of almost bothy proportions, its architect had shoe-horned a living room, a kitchen, two bedrooms, and (wonder of wonders) a separate bathroom and toilet. They were supposed to last 10 years. Ours stood for 30.

The kitchen table and the ironing board folded away into the wall. In my parents’ bedroom there was a “linen cupboard” (also known as the dirty washing bin) I could climb into and hide in. There were fitted wardrobes, a press in the living room and a larder in the kitchen. There was a gas cooker, a gas fridge, an immersion heater and a boiler. The fire also heated the water.

It was the age of the radio, and utility furniture that betrayed its origins by having the government arrow stamp on it. It was a triumph of function over style. Our big Philips radio was a kind of totem in the corner, our connection to the wider world.

The Glamis Road prefabs stood on the northern slope of the Balgay, and in its winter shadow.

They were arranged along communal paths at right angles to the road, eight or nine to a path, so each path effectively became its own community.

I can still name them all: the Cathros, the Crumleys, the Whites (later the Mahoneys), the Napiers (later the Vales), the Donnets, the Coulls, the Elders, the McRaes, and the Speeds.

Where are they now?

In my earliest memories of it, Glamis Road was the last street in town. Across the road from the start of our path, Elmwood Road was a country lane that ran uphill between the fields of Hillside and Backhill farms, to a low ridge that looked north to the Sidlaws. The view down the street was to the Tay and Invergowrie Bay, as it still is.

The sound in my head whenever I think of the place is of geese overhead. The very first utterance on the first page of the first of a quartet of books about the seasons which I have just completed was in its own way a tribute to all that.

“One September day in the fourth or fifth autumn of my life there occurred the event that provided my earliest memory, and – it is not too extravagant a claim – set my life on a path that it follows still.

“I was standing in the garden of my parents’ prefab in what was then the last street in town on the western edge of Dundee. An undulating wave of farmland that sprawled southwards towards Dundee from the Sidlaw Hills was turned aside when it washed up against the far side of the road from the prefab, whence it slithered away south-west on a steepening downhill course until it was finally stopped in its tracks by the two-miles wide, sun-silvered girth of the Firth of Tay at Invergowrie Bay.

“The bay was an autumn-and-winter roost for migrating pink-footed geese from Iceland, and one of their routes to and from the feeding grounds amid the fields of Angus lay directly over the prefab roof. Ever since, the sound of geese over the house – any house – has sent me running to the window or the garden. So was established my first and most enduring ritual of obeisance in thrall to nature’s cause, that September when I looked up and for the first time made sense of the orderly vee-shapes of their flight as they rose above the slope of our street, up into the morning sunshine…When they had gone…I felt the first tug of a life-force that I now know to be the pull of the northern places of the earth…”

The prefab was a regular gathering place for the wider family. Ours was the kind of family that was forever visiting each other. New Years were best. The concept of the “party piece” was in its heyday, which is not quite as awful as it sounds for ours was also a family in which music flourished. We never had a television set in all the prefab years, but we had the only piano in our path.

Treasury of memories

Mum was the archivist, the one who insisted on recording prefab life on crappy little black and white cameras. The snaps were filed in a large cardboard D.M Brown’s dress box. Incredibly, it still survives and still holds its treasury of memories. It now lives with my brother Vic in Burton-on-Trent, so when I was asked to contribute a few prefab memories I asked him to rake around and see what we could unearth.

In a way, they speak for themselves, but looking at their digitised ghosts on my laptop screen, the years fall away, and there is an old familiar scent in the air, a scent of coal fires and linoleum.

Mum and dad and three of my grandparents are buried in the Balgay, so in another way, we never really left the place. It certainly never left me.