They were the north-east duo who flourished under Bill Shankly in his glory days at Liverpool FC.

And although they experienced different fortunes, with Ron Yeats making the move from Dundee United and leading the Anfield club to unprecedented heights in the mid-1960s, while George Scott arrived in Merseyside as a callow teenager and left with thoughts of what might have been, they both grew to cherish their association with the legendary Shanks.

Ron Yeats

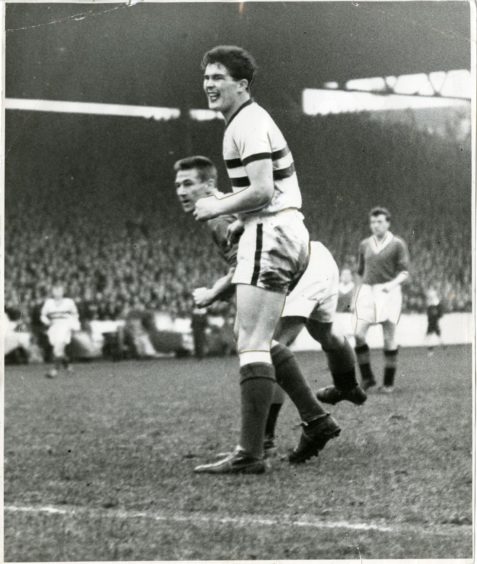

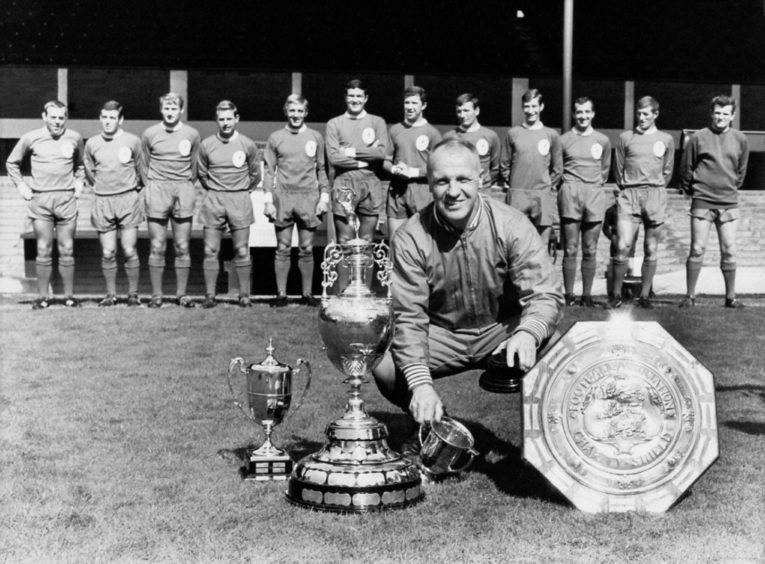

Yeats, a redoubtable figure who struck fear into opponents, and advanced from the Aberdeen Lads Club to become the first Liverpool captain to lift the FA Cup in 1965, was a colossus who commanded respect and there are plenty of stories about his grisly strength, not least the time when Shankly was so impressed with his new signing that he told a group of journalists: “The man is a mountain, go into the dressing room and walk around him”.

His intimidating presence explained why he was installed as captain just six months after switching from Tannadice as he took charge of affairs with a magisterial authority, prompting Shankly to declare: “With him in defence, we could play Arthur Askey in goal!”

Rowdy, as he was known by the supporters, skippered his charges to their first league title in 17 years in 1963-64, but that was just a taste of things to come.

The following season proved one of the most momentous in Anfield history, and not just because it yielded their maiden FA Cup triumph with a 2-1 victory over Leeds United.

In August 1964, Yeats, who had served his apprenticeship as a slaughterman at Aberdeen Cattle Market in Hutcheon Street – not far from where Scott and his family lived in Spring Garden – led his team-mates on a journey into the unknown when they played their inaugural European match in Reykjavik.

As Scott related: “Working at the cattle market was an inauspicious start for a Liverpool legend and I still vividly remember the awful smell and the wailing of the animals.

“It’s also strange to think that he had an unsuccessful trial with Elgin City.

“But once he went to Dundee United, who were Scottish Division Two part-timers at that stage, Ronnie played a huge part in getting the Tannadice side promoted to the top flight and, within a few years, he was starring with Liverpool and leading them into European battles.”

After their win in Iceland, it was the skipper who famously guessed right when Liverpool eliminated Cologne on the toss of a coin in a replayed quarter-final.

The 1964-65 campaign also saw the club ditch its white shorts, and it was Yeats who was chosen to model the new all-red kit. His manager was convinced the move would intimidate opponents – and if the sight of his centre-half was anything to go by, he was right.

George Scott

Scott, for his part, was one of the Shankly luminaries who followed in the footsteps of the Busby Babes, on a long and winding road from Torry to Liverpool and then Port Elizabeth.

Even now, 60 years after he left the Granite City at just 15, against his parents’ wishes, and journeyed further than he had ever gone before to Merseyside, there’s a sprightly tone in his voice when he talks about his peripatetic football career, which he has chronicled in an autobiography, The Lost Shankly Boy.

It’s a compelling story, which includes an extraordinary array of anecdotes about Scott staying in digs with Anfield legend Tommy Smith, returning to Aberdeen FC and running rings round Scotland and Rangers great John Greig, being employed as a security guard in a South African shanty town and working as a sales rep when he met Hollywood star Elizabeth Taylor.

And there is even the reference which Liverpool’s legendary manager, Bill Shankly, wrote for him after the youngster sustained a serious cruciate ligament injury in 1966.

It’s on official club notepaper and states: “Dear people, George Scott played for my club under my management for nearly five years and, during that time, he never caused anybody any trouble. I would stake my life on his character.”

Squad player

Scott clearly thought the world of Shankly and, amid the Swinging Sixties, that passion was reciprocated, even though the north-east player couldn’t quite break into the First XI in an age where there were no substitutes.

He said: “I was in the squad for the FA Cup final in 1965 and Shanks later described me as the 12th best player in the world.

“He had this aura about him which made you realise why he gained such an exalted reputation. You always felt his presence even before you saw him and he had a way of building you up.

“I remember he came up to me and said: ‘By heavens George, you’re looking fit. I heard you scored four for the reserves on Saturday. Well, there was a lad in the other side who is going to play for England and he never scored at all’.

“He was talking about Alan Ball. These comments and the way he treated you properly had a way of giving you a positive lift.

“Bill was amazing – probably the greatest football man who ever lived – and he looked after me long after I had left the club.

“I always said five years with Bill was worth ten years at any university.”

He was close to his fellow Aberdonian, Yeats, during their time at Anfield, but the pair had previously forged an allegiance in the Granite City.

Scott recalled: “I first met Ronnie long before he joined Liverpool – at Aberdeen Lads Club around 1957. I was about 12 years old, and Ronnie had just signed for Dundee United.

“He was attending an event to present prizes to the young players, but even then, he was a giant and especially compared to me, a scrawny primary school pupil.

“Ronnie and Ian St John became the two biggest pieces in Shankly’s jigsaw. For me, he was the Virgil van Dijk of his day. He dominated every game he played in and, for a big man, his distribution of the ball was excellent and he always seemed in control of any situation.

“Off the field, he was a gentle giant and was always willing to give advice and support to the youngsters. We all had the greatest respect for him as a man and a wonderful captain.

“Ronnie often struggled to cope with close-season boredom and it reached the point where he put the word out that he was willing to take up some sort of part-time job.

“One of the directors, Syd Reakes, who later became chairman, heard the banter going round, and shouted to us: ‘I think I know what would suit you in the summer, Ronnie, a lifeguard job on Formby Beach’.

“Tommy Smith responded: ‘That’s no good, Mr Reakes, he’s not a good enough swimmer’.

“But Bill Shankly had been standing at Tommy’s shoulder and immediately remarked: ‘That would be no problem, son. Look at him, Ron could wade out to sea for two miles!”

Scott, who had been recommended to the Anfield club by his school caretaker Jim Lornie, returned to his roots and received a signing-on fee of £1,000 at Pittodrie, which he spent on a new car, and drove it out of the garage in a spirit of giddy exhilaration.

Why not?

He was still just 20 and made an instant impact in his early days at Aberdeen.

He recalled: “I had supported them since childhood, so I was determined to prove what I could do and I scored on my debut after just 13 minutes against Clyde.

“Next up were Rangers and our supporters were thrilled when we beat them 2-0 at Pittodrie in front of a crowd of 28,000.

“There were nine Scottish internationalists in the visiting team that day, including the Scotland captain Greig, but I remember putting the ball through his leg while nutmegging him and hearing him chasing me and asking in very strong terms the name of the hospital I would prefer to wake up in if I ever did it again.

“I felt really confident about my future, but sport can be cruel and when I suffered the cruciate injury, I was released at the end of the season in the summer of 1966. I was out of work at 21, having left school at 15, with nothing to fall back on and no qualifications.”

Scott has never been afraid to embrace fresh challenges. After receiving his prized reference – which was printed with one finger on Shankly’s little typewriter – he worked in a biscuit factory, before joining South Africa Premier League team Port Elizabeth City.

He and his fiancé Carole were married on July 30 1966 – the same day England won the World Cup – and he enjoyed significant success in the Cape as the league’s leading scorer.

Racism

However, he was appalled at the pervasive influence of apartheid in the country – “I would play football in the streets with the local black kids, but was told not to, because it wasn’t the done thing and wasn’t ‘right’, and seeing such racism up close was shocking” – and the couple came back to the UK in 1968.

Once again, the Shankly testimonial proved invaluable when he attended an interview with Nestle at the Adelphi Hotel in Liverpool city centre. He was hired on the spot and subsequently enjoyed his tryst with acting and political celebrities.

He said: “Elizabeth Taylor was promoting her perfume at the Ritz in Paris and I was there with some other sales guys. While she was chatting to us, her personal assistant came over and told her that she had a guest.

“Well, it just happened to be Henry Kissinger. We sat there in disbelief as he walked in and they started talking. It was a brief taste of a totally different world.”

Scott is a blithe character, somebody who has just recovered from five-way bypass surgery in hospital and, although he lives in Liverpool, he still relishes his links with Aberdeen.

Sad to relate, Yeats is now stricken by dementia in a Merseyside care home and, at 82, is a very different person from the charismatic individual who wowed the Kop in his pomp.

One wishes the pair well as they continue in the autumn of their lives.