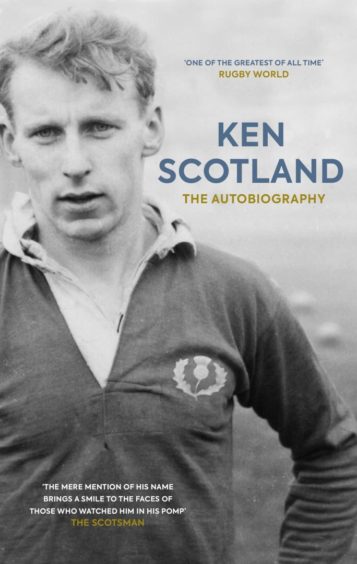

He was the man with the name of the country he graced on the international rugby field.

And even today, more than half a century after Ken Scotland thrilled supporters and tormented opponents with a feint and a shimmy, a sidestep and delicious sleight of hand as the prelude to sparking fresh mayhem in a No 15 shirt, he remains one of the most gifted performers in the history of the game.

Yet, while he amassed 27 caps and was selected five times for the British and Irish Lions, Scotland played in an era when the sport was strictly amateur, which helps explain why he spent many of his best years at Aberdeenshire RFC on makeshift pitches in the north-east mud and glaur and where he encountered the best and worst of life on the grassroots circuit.

Compelling reminder

A modest, self-deprecating character without a trace of arrogance in his body, the Scot preferred to orchestrate attacking rugby on the pitch rather than blowing his own trumpet.

But now, at 84, he has written his autobiography and it offers a compelling reminder of why Rugby World magazine described him as “one of the greatest of all time”.

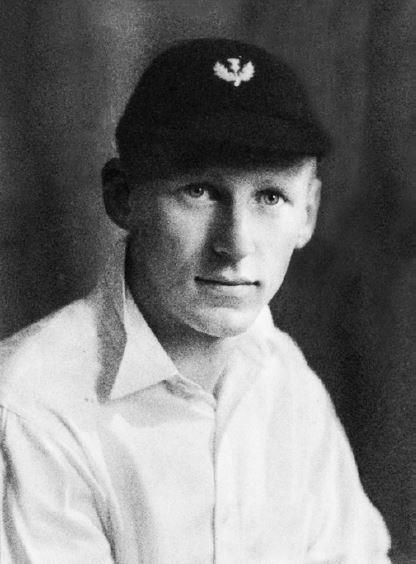

Most Scottish aficionados will probably regard Gavin Hastings or Andy Irvine as their country’s best-ever full-back, but Ken was up there in the stratosphere with them. And, from the moment he made his debut against France in 1957, he caught the eye of the cognoscenti.

More importantly, he was as cool as Antarctica during that debut at Stade Colombes and kicked all the points in his side’s 6-0 victory. Yet, while he enjoyed the experience and revelled in the post-match camaraderie, where “all sorts of strange drinks were flowing”, the 20-year-old was still regarded as being rather wet behind the ears.

He recalls: “The next day, the London edition of the Sunday Express printed the following: ‘Amid popping corks and good-natured bonhomie, sat a pale-faced, slim-chested young man in a kilt, sipping a pineapple juice, quietly taking in the scene with the casual confident air of one used to dining on the Left Bank six nights a week instead of in a British Army mess’.

“A more accurate headline would have been ‘Legless at the Lido’, but at least that piece of creative journalism did my reputation no harm.”

There was, however, another sign of the lost world of amateurism. The Daily Record awarded Ken their Sports Star of the Month prize – a travelling clock – but…”The SRU would not permit me to accept it or I would have professionalised myself.”

The youngster’s mercurial qualities were evident, but he couldn’t rely on them to make his way in the world. Instead, he spent a large part of his working life with the National Trust of Scotland, methodically looking after myriad grand dwellings and majestic properties.

This meant he had to travel throughout his career, which is one of the reasons why he turned out for more than 30 different teams across Britain, from Heriot’s FP to Cambridge University and Ballymena to Lurgan and Leicester, and thence on to Aberdeenshire.

No regrets

He ended up there because he couldn’t play for Aberdeen Grammar or Gordonians, the region’s leading clubs, which were only open to former pupils of their respective schools.

That, in itself, demonstrates how much rugby has changed since the 1960s. But Ken had no regrets about joining Shire. In fact, he played more games for them – 89 – than anybody else on his magical mystery tour. And he has plenty of different memories of those contests.

Ken and his wife Doreen moved into a comfortable modern flat in the Rosemount area of the Granite City and he started in his new role with Alexander Hall & Sons, the major all-trades building contractors in the north of Scotland.

A keen cricketer, he soon made himself available for Saturday games at Aberdeenshire CC and was regularly in the thick of the action at Mannofield as a wicket-keeper batsman. And he made a sufficiently positive impression to be capped for his country in the summer game.

But, at that stage, Ken’s focus was primarily on rugby and dealing with the culture shock which awaited him as he geared up for his new challenge.

He recalled: “The Arctic weather conditions in early 1963 did nothing to help when I joined Aberdeenshire in late January and it was not until well into April that it became possible to play a match. During this period, the average numbers at training stayed steadily at three – a number greatly below that which patronised the upstairs bar in the George Hotel every Saturday evening.

“After months of inactivity, it took a heroic effort to put a team out on the field. It seemed to me, as a newcomer, that players had been borrowed from every club in Aberdeenshire and our motley appearance might have confirmed that view.

“The game introduced me to the delights of their changing room and pitch at the Chanonry. The amenities failed to match, by some way, those I had become accustomed to at Cambridge or Leicester – it had one communal changing room, for both teams and the referee, and was completely devoid of either artificial light or running water.

“I also discovered that a knowledge of the contours of the pitch was always a distinct advantage to the home side. The expression ‘hanging lie’ had a usage in rugby which I had only previously known in golf.

“But adversity brings out the best in a person. During my six or seven seasons with Aberdeenshire, I had the privilege of meeting many players at their best. This was especially true of away games where, inevitably, either the quality or the quantity of the team left much to be desired.

“I must not leave you with the impression that the Aberdeenshire of the mid-sixties was a disaster area. My memories are of great enjoyment, both on and off the field, and also of great admiration for the small and enthusiastic nucleus of officials and players who helped provide the continuity from one generation of players to the next.”

Ken was involved in the epic Lions tour of Australia and New Zealand in 1959, which stretched from May to September and featured a staggering schedule of 33 matches, with the tourists winning 27 and losing six.

Canada tussles

In Australia, the Lions dominated, triumphing in both Tests and only suffering one defeat. However, their gruelling exertions in New Zealand eventually took a toll on the players, who found themselves tackling 25 fixtures, of which they win 20. Nowadays, such an itinerary would be unthinkable – but the organisers also lined up a couple of tussles with Canada, just in case any of the participants were desperate for more rugby.

As Ken recalled: “Prior to leaving the UK, we spent an intensive week training together as a squad in Eastbourne. For all but the Scots in the party, this was their first introduction to our manager Alf Wilson.

“His only travelling support was Ossie Glasgow, secretary to the touring party, an Ulsterman and a former international referee.

“They were a good combination. Alf could be quite fiery and outspoken while Ossie was a placid pipe-smoking smoother of ruffled feathers. Ossie probably had more direct dealings with the players because he weekly handed out our expenses of 10 shillings a day and packets of cigarettes to anybody who was interested.

“There weren’t many smokers, but one or two of the lads took them because, like being in jail, they were a form of currency.“

In Australia, Ken experienced at first hand a local custom called the “six o’clock swill”.

As he explained: “The local pubs were only open for an hour each evening, so there was an almost manic necessity to drink quickly. Little glasses called ponies were lined up along the bar and filled with beer from a hose.

“Then, all of a sudden, the locals would appear and go: wallop, wallop, wallop, wallop – and they’d get as many of them down as they could before the bar closed an hour later.”

He admitted it was a relief once the match schedule commenced and he was in the thick of the battle across the two countries for the next four months.

And there was to be a further meeting with the All Blacks five years later – in Aberdeen.

By 1964, Ken was a pivotal member of the North and Midlands squad which took on a formidable New Zealand contingent at Linksfield in the city.

Even if they had planned and trained together properly, it would have been a massive challenge for this collection of players from Aberdeen, Inverness. Dundee and Fife.

But as Ken, who skippered the team, has revealed, there was no effort in advance to devise tactics or fathom how to block the Kiwi juggernaut.

He added: “To say that our preparation to play the All Blacks was amateurish would be a huge understatement. With the kick-off timed for 2.15 at Linksfield, the side met for an early lunch in a local hotel.

“I was captaining the side from stand-off and, having introduced myself to several in the team whom I had never met, I attempted to lay down some basic tactics.

“In the line-out, I suggested we should jump at three and five and turned expectantly to the two second rows to see which one preferred to jump at the front or the middle, only to be told by one of them that he didn’t jump because he was usually a prop.

“Fortunately, Mike Gibb was big for a prop, but it meant a very busy afternoon for his second-row colleague, the athletic Ian Wood, later of oil industry fame.

“In the event, we punched well above our weight and kept the score down to a 15-3 defeat.”

Dipping into Ken’s book is rather like being transported back to the world of Ealing comedies and Beatlemania.

But nothing should detract from the enjoyment and joie de vivre which permeates the reminiscences of one of international rugby’s most legendary characters.

Ken Scotland: The Autobiography is published this month by Polaris.