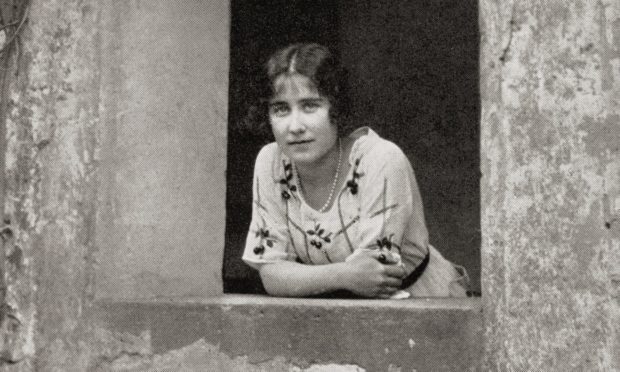

The Queen Mother was just 15 when she witnessed the deaths of two airmen in a wartime tragedy which cast a dark cloud over Angus.

Elizabeth Angela Marguerite, who would be queen to King George VI and mother of the current monarch, watched a plane plummet to earth in a flying accident in the grounds of Glamis Castle on Thursday October 14 1915.

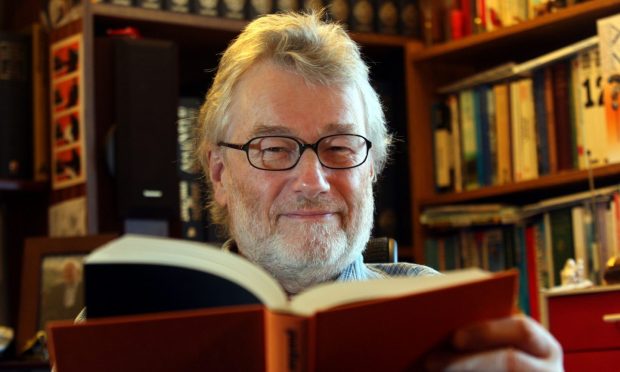

Dr Tom Thorpe, Trustee, Western Front Association, said the crash may be a minor event in the context of the First World War “but its legacy is still important today”.

Montrose

The two airmen were pilot Lieutenant Allan Herbert Hardy and observer Captain Frederic George Alleyne Arkwright.

They were attached to 6th (Reserve) Squadron, Royal Flying Corps (RFC) at Montrose.

The day before, Wednesday October 13 1915, they were out on a training flight from Montrose in a Farman Shorthorn biplane when a mechanical problem compelled them to make a forced landing in the castle grounds.

Dr Thorpe said: “A new propeller was ordered from the base at nearby Montrose aerodrome and it is thought that the flyers stayed overnight at Glamis Castle until the new prop could be delivered and fixed to the aircraft.

“Both men were typical of the type of flyers with the RFC at the time.

“At the time of his death, Arkwright was 29 years old and a regular army officer since 1905.

“He was a former pupil at Eton and was the son of Mr F C Arkwright of Willesley, Matlock.”

Captain Arkwright had been wounded whilst serving with the 11th Hussars in November 1914.

Recovering from his wounds, he decided to study aviation, and had become attached to the RFC just several months before he was killed.

Lieutenant Hardy was 25 years old and was the son of the landowner Colonel Hardy of Chilham Castle, Kent.

Hardy senior would go on to be MP for Bradford after the war.

Dr Thorpe said: “Glamis Castle was the ancestral home of Elizabeth’s parents, Claude Bowes-Lyon, Lord Glamis (later the 14th Earl of Strathmore and Kinghorne) and Cecilia Cavendish-Bentinck.

“Elizabeth was their ninth child and may well have met the airmen as they were entertained by her parents on the Wednesday night.

“She certainly witnessed the accident.

“Once the new propeller was fitted to the Farman on the Thursday morning, the pilot, Lieutenant Hardy, opened the throttle and the plane took off on its return journey to Montrose.”

It was reported that the plane climbed to about 100 metres, circled Glamis Castle and then was reported to get into difficulty.

Before the eyes of the horrified onlookers, the plane fell from the sky at a terrific rate, midway between Forfar and Glamis Castle into a field known as Lyon’s Moss.

The fall was followed by a loud crash and explosion and workers in the fields hurried to the scene of the accident and found the machine overturned and the mangled remains of the unfortunate officers underneath it.

Both men had been killed instantly but efforts were immediately made to remove the bodies from the wreckage.

Forfar Infirmary

The remains of Captain Arkwright and Lieutenant Hardy were taken to the mortuary at Forfar Infirmary before they were conveyed in hearses to the railway station and taken south by train for burial in their home areas of England.

Dr Thorpe said: “Why did the accident happen?

“The story would suggest that mechanical problems with the Farman may have been the reason for the crash.

“The Farman Shorthorn was known as a ‘pusher’ aircraft with the rear facing propeller behind the crew pushing the plane forward.

“The Farman was withdrawn from British frontline service in 1915 but still used for training.

“The crew had to be careful not to drop objects out of the cockpit as the slipstream could force these to smash into the propeller behind them.

“Pilot error could have been another cause as Allan was inexperienced having only obtained his Royal Aero Club Certificate, his Edwardian flying licence, on September 21 1915.

“Unfortunately, crashes of like this were not uncommon.”

The air forces of the British armed services saw a huge expansion in size and machines over the course of the war.

In 1914, the Royal Naval Air Service and Royal Flying Corps had 277 planes but by the Armistice the Royal Air Force, which was formed from the RNAS and RFC, had 22,647 aircraft.

Fatal accidents

With this rapid growth came a huge learning curve as the new pilots sought to learn how to fly.

Historians have suggested that more than half of the 14,166 British pilots killed in the Great War were as a result of fatal accidents but these figures are difficult to verify.

Dr Thorpe said: “This fatal accident that killed two airmen may seem a minor tragedy compared to horrific fighting in the trenches and blood, death and mud of the Western Front.

“However, this incident, that happened 105 years ago this month, has important legacies that are worth considering.

“Firstly, it is important to remember all those who died in the Great War, regardless on which side they fought, how they died or whether they were combatants or civilians.

“The Western Front Association was formed in 1980 to maintain interest in the Great War and to perpetuate the memory, courage and comradeship of those on all sides who served their countries in France and Flanders and their own countries during the Great War.

“These two airmen had lives, families and stories which are worth telling even if they did not die in the heat of battle.

“Secondly, this incident demonstrates that the Great War had a massive impact on all levels of society across all parts of the UK.

“Even though Lady Elizabeth was living a sheltered life of wealth as a titled aristocrat in a Scottish castle miles from the frontline, her isolation and privilege did not prevent her from witnessing the death and destruction of war, even if it happened by accident.

“Indeed, this incident may well have added to her distress as it is highly probable that she was worried about her brother Fergus, an officer in the Black Watch regiment, who had been reported missing in September after the Battle of Loos (he was later assumed killed).

“Later on during the war, she also witnessed the impact of war first hand when Glamis Castle was turned into a convalescent home for wounded soldiers, which she helped to run.

“Finally, it is important to actively remember our history, especially at a local level.

“There have been calls for a memorial to mark their death on the site of the crash.

“Too much of our history is based on common myth rather than solid fact.

“Consider how popular perceptions of the Great War have been shaped by BBC TV’s 1980s comedy Blackadder Goes Forth.

“Many people still believe that characters like cynical Captain Blackadder, bureaucratic Captain Darling, insane General Melchett and stupid Lieutenant George were typical of the British officer in the conflict.

“However, far more representative of the actual British Army officer (the RFC was then part of the army) were men like Lieutenant Hardy and Captain Arkwright.”

War memorial

Captain Arkwright was also well-known in sporting circles as an excellent horseman and he is buried in Cromford in Derbyshire.

Lieutenant Hardy was laid to rest in Chilham in Kent.

Both casualties were recorded as being casualties of the Great War and listed under the Imperial War Graves Commission.

Captain Arkwright is listed on a war memorial in Cromford village and on the Matlock War Memorial and the 15 names on the Starkholmes War Memorial as well as a plaque in St Mary’s Church recording that he was “killed whilst flying near Montrose”.

Lieutenant Hardy’s name is listed among the men of Chilham “who gave their lives for England in the Great War” on a war memorial in St Mary’s Churchyard in Chilham in Kent.

His name also appears on a stained glass window in the Chilham Parish Church.