With 2020’s Remembrance Day upon us, Michael Alexander speaks to the author of a new book which challenges the accepted view that Britain’s involvement in the First World War was universally popular –and spotlights Dundee’s role at the “epicentre” of the anti-war movement.

When 77-year-old Cyril Pearce was a research student at Birmingham University in the 1960s, he explored the history of the Independent Labour Party (ILP) within the textile communities of the West Riding of Yorkshire.

During that time, he met people who had been active in the ILP before the First World War, and they all talked about how workers and trade unionists in his home town of Huddersfield had been particularly staunch in their opposition to the 1914-1918 conflict.

Having gone on to get married and become a secondary school teacher and college lecturer, Cyril returned to the subject in the 1980s when he started researching his 2001 book Comrades in Conscience: An English Community’s opposition to the Great War.

The book explored how Huddersfield was a hot-spot for anti-war activity during the First World War where many members of the ILP and the British Socialist Party – the ‘Left’ in general – went on to become Conscientious Objectors (Cos) with many going to prison and branded traitors by the British state.

However, his work also raised the question – was Huddersfield unique in its anti-war stance or were there other places like it?

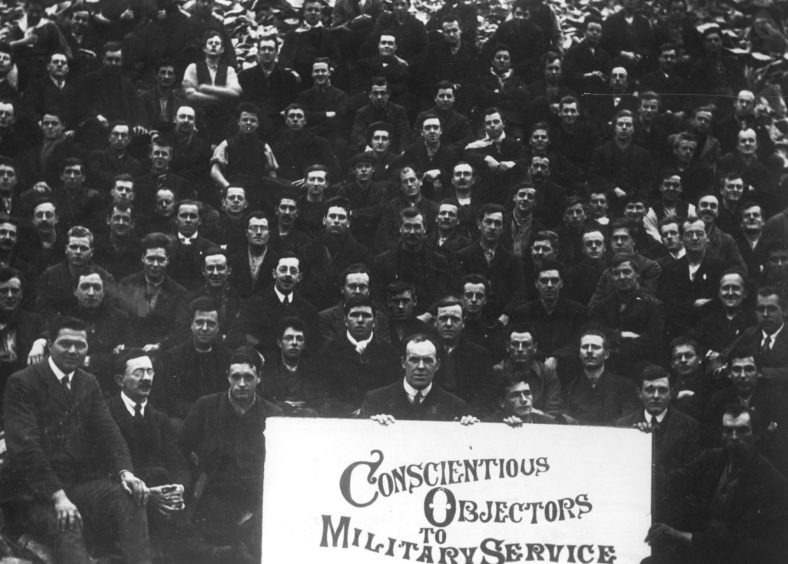

Now, after 20 years’ detailed research trying to find the answer, his latest book Communities of Resistance: Conscience and Dissent in Britain during the First World War, brings together the stories of almost 20,000 COs from across England, Scotland and Wales and challenges the accepted view that Britain’s involvement in the First World War was universally popular.

Using the numbers for Huddersfield as the touchstone and a detailed study of more than 40 specific communities across Britain, he has concluded that Huddersfield, while still important, can no longer claim to be the most important war resister ‘hot spot’. That mantle has passed to Bristol.

In some ways, however, he has concluded that Dundee’s story was even more remarkable.

It had more COs than Huddersfield – 129 as opposed to 121, he said. But, along with Edinburgh, the strength of its anti-war community proportionately outranked that even of Glasgow.

Indeed, he’s concluded there was much about Dundee’s war resisters which challenged ‘Red Clydeside’ as the heart of radical Scotland.

Its anti-war alliance between the temperance movement in the shape of the city’s post-war MP, Edwin Scrymgeour, with his newspaper the Scottish Prohibitionist, and the local branches of the ILP have no parallels anywhere in Britain.

“It was the numbers for Dundee that really stood out when I worked out the COs as a proportion of men available for military service,” explains Cyril, a retired academic from a working class family, whose ex-miner, staunch trade unionist father met his mum while working in a Huddersfield textile factory.

“I think the important thing about Dundee was the strength of the local labour movement and the alliance between the local labour movement – the ILP, the Trades Council – and the alliance between them and Scrymgeour and the prohibitionist organisations.

“There’s something similar down south in Croydon where one of the leading anti-war figures was himself a prohibitionist. But there’s nothing on the same scale as Scymgeour and the prohibitionist group offered in Dundee.

“With the support of Scyrmgeour’s own newspaper – the Scottish Prohibitionist – it makes for a very significant presence in Dundee politics.”

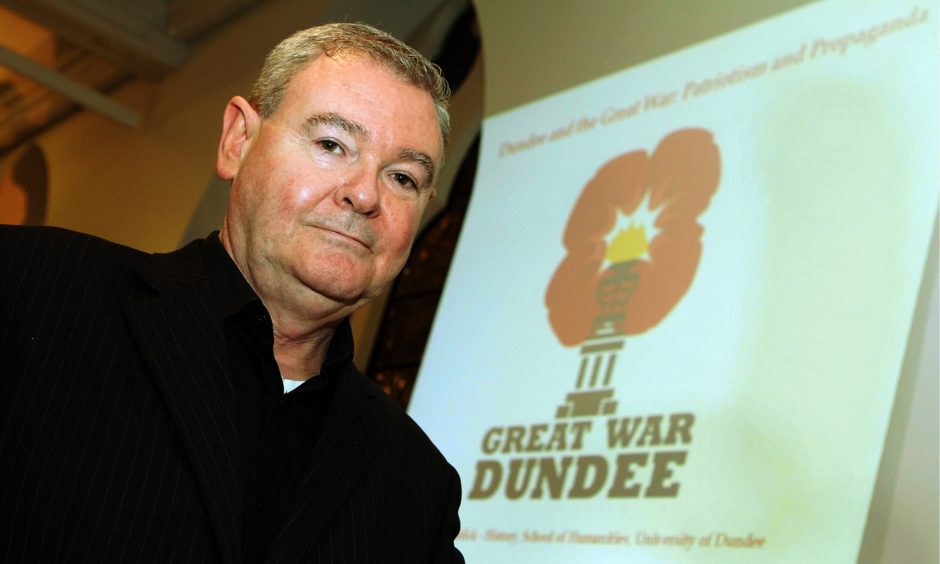

Cyril made several research trips to Dundee where he met with members of the Dundee in the First World War research group and had conversations with Dundee war historian Dr Billy Kenefick.

He was particularly interested when Billy sent him a copy of a feature from The Courier dated May 2018 which contrasted the tragic losses afflicted on the 4th battalion Black Watch at the Battle of Loos in 1915 – a time when Dundee had one of the highest military recruitment rates anywhere in Scotland – with the Dundee men who refused to fight on the grounds of morality or religion.

The article told how Dundee was the “epicentre” of a very well organised network of support for COs and war resisters.

Regular collections took place every Sunday outside the Dundee High School gates to support the dependents of the COs when they were in prison.

About 70% of COs were Independent Labour Party members or associated with John Maclean’s Scottish section of the British Socialist Party which was anti-war and very Marxist.

Other groups included The Socialist Labour Party, the Union of Democratic Control and the Women’s International Peace movement.

The article explained that not all COs were pacifists. They were anti-imperialist if they were political and as far as they were concerned this was a war being fought for capitalist gain and capitalist greed.

Another reason for objection was the fact Britain went to war in World War One without an Act of Parliament.

The left wing movement always argued that the peoples’ representatives should decide if Britain went to war or not.

Yet some local newspapers would call them ‘pro-German’.

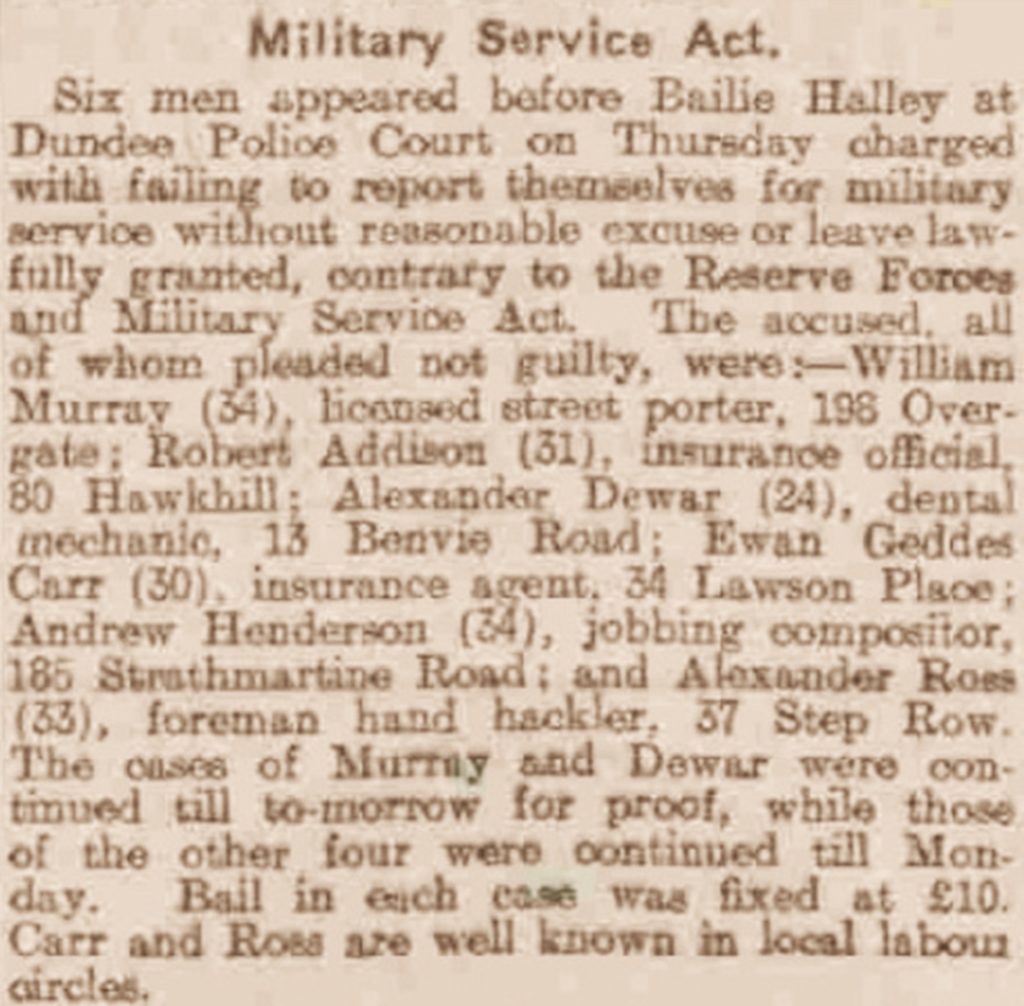

One story that caught Cyril’s eye was that of two Dundee brothers – Ewan Geddes Carr (socialist and war resister) and William Stewart Carr (socialist and soldier) who were very well known socialists in Dundee before 1914.

They were both against the war and were already talking about being conscientious objectors should a war take place.

But when war actually came, their positions became very different.

Ewan Geddes Carr was a socialist who became a war resister within the Independent Labour Party and eventually a conscientious objector who ended up in prisons and work camps – including Wakefield Work Centre, where there was even a Scottish football team.

His brother William, however, joined up in London after taking the view he had to see the war through.

It’s estimated that during the First World War some 16,000 conscientious objectors refused to fight across Britain as conscription laws enlisted 2.5 million extra British troops from 1916 onwards.

Those who objected had to appeal in public, usually on moral or religious grounds.

However, it was not an easy process and most of the men and women who stood by their own judgements on the war were jailed, sent to hard labour camps and socially exiled as the authorities viewed them as traitors.

Cyril was also interested to learn Dundee’s COs were a “fairly hard core lot” – many of whom refused to compromise with non-military government schemes.

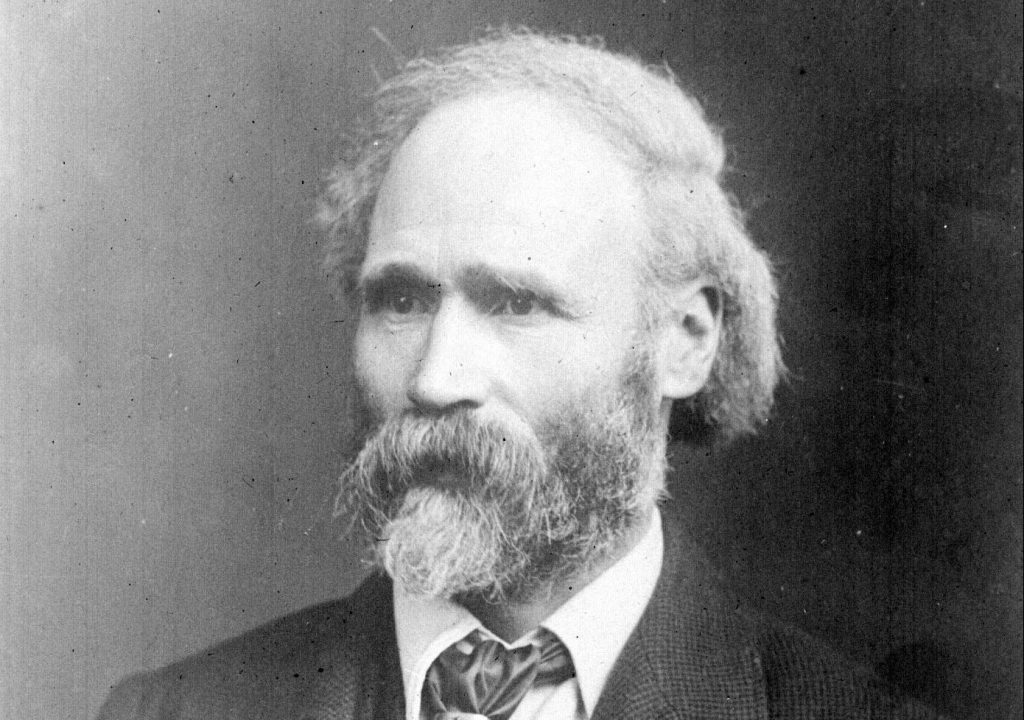

One example was Bob Stewart – a Dundee ‘absolutist’ conscientious objector.

A trade unionist, socialist, former Dundee town councillor and prohibitionist campaigner, he appealed as a CO and claimed his full-time trade union work was essential.

However, Dundee Military Service Tribunal did not agree and refused his appeal.

In December 1916, he was arrested for failing to answer his call-up, tried in Dundee Police Court, fined £2 and handed over to the army.

He was court martialled three times for disobedience, served sentences in Dundee prison and in Edinburgh’s Calton prison.

As an ‘absolutist’ he refused to accept any government schemes, went on hunger strike in March 1919 and was released in April 1919.

After the war he continued his trade union work and became a leading figure in the Communist Party.

Cyril says another important consideration of the time was the socio-economic context.

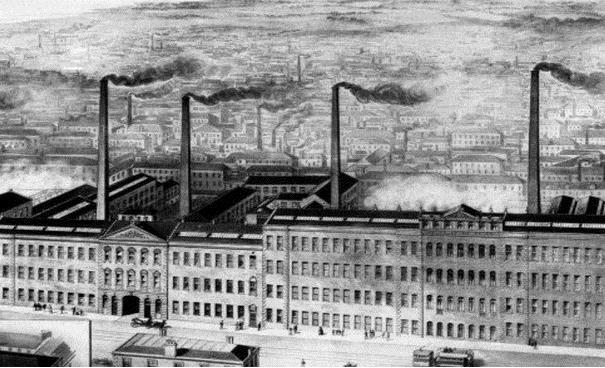

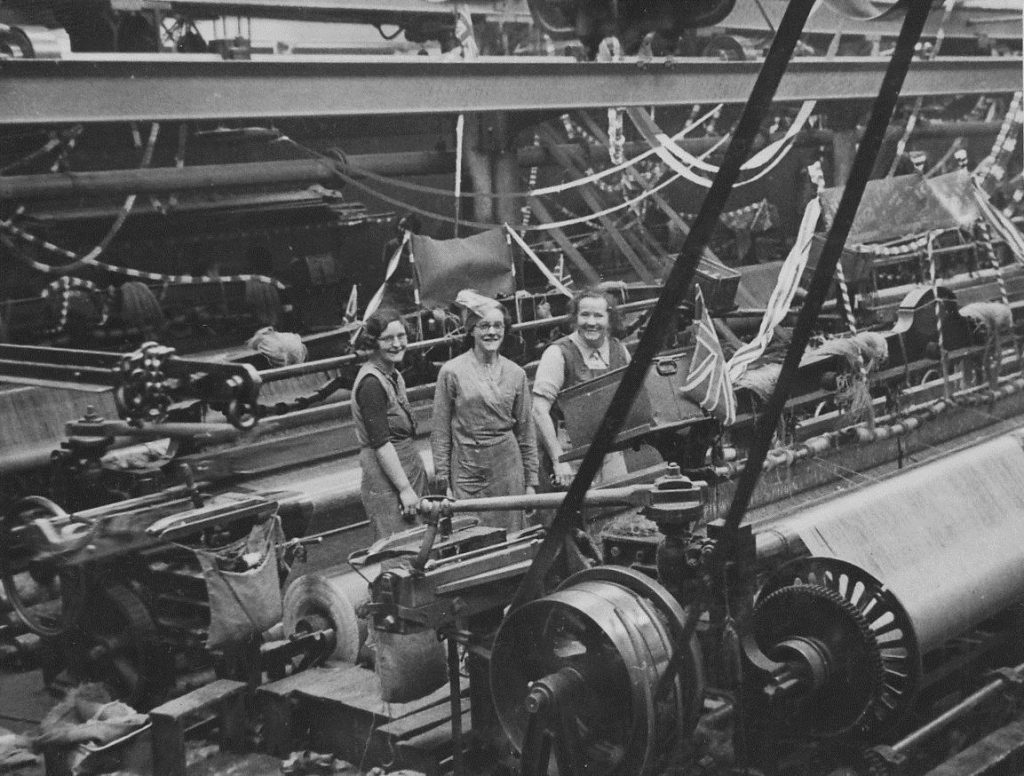

By the standards of the time, Edwardian Dundee was prosperous and its economy buoyant thanks to “jute, jam and journalism”. To that could be added fishing and shipbuilding.

However, that prosperity did not extend to the whole population.

Living standards for the working classes were very poor and, coupled with the influx of labour during the expansion of the jute industry resulted in insanitary, squalid and cramped housing for much of the population.

It was a setting in which the labour and socialist movement had established itself quite early.

The formation of Dundee Trades Council in 1888 coincided with Keir Hardie’s first major initiative in independent labour politics in the formation of the Scottish Labour Party.

Its Dundee branch was represented at the foundation of the ILP in 1893 and became Dundee ILP.

In 1906, with the trades council, it formed a local Labour Representation Committee

(LRC) and the alliance was immediately rewarded by the election of Alex Wilkie as MP for the city, one of Scotland’s first Labour MPs.

Two years later his colleague as the second of Dundee’s two MPs was the then Liberal Winston Churchill.

When war broke out Dundee ILP took the anti-war line and, although there were no Dundonians among the names of NCF (No Conscription Fellowship) members in February 1915, by November that year, largely as a result of a meeting organised by the ILP, a Dundee branch had been formed.

Two months later, in January 1916, the introduction of the conscription bill widened the membership of Dundee’s anti-war network with the formation – perhaps belatedly – of the Dundee Joint Committee Against Conscription.

Thereafter, the city became a stronghold of a growing anti-war movement led by the ILP and NCF along with others including the Women’s Peace Movement drawn from Dundee’s anti-war suffragette community.

But if there’s a sub text to his book, it’s about acknowledging that these people have been “wronged” by history and about trying to tell people what “really happened”.

“There’s always been time to tell the story again, but perhaps now with access to records, with the use of computers and the internet, we can get much closer to a fully detailed story, and that’s only really been possible over the last 20 years,” he adds.

“So yes it is time, but it’s always been time to tell a different story about the First World War.”

· Cyril Pearce’s Communities of Resistance: Conscience and Dissent in Britain during the First World War, published by Francis Boutle Publishers, is out now.