Was a highly-dangerous German spy network operating in Dundee and Arbroath just four years before the outbreak of the First World War?

The mysterious ‘Colonel Seton’ delivered a gloom-laden talk at the Butterburn Hall in Dundee in 1910 on “Our Needs in National Defence”.

He spoke about a state of warfare which might be brought about sooner than suspected through the ambitions of the Germans.

He said Germany sent spies to Britain and at the present time to his knowledge there were several who were comfortably located in Dundee and when submarines came to the city they were there taking photographs.

Train station

A new train station was being constructed in Arbroath and he had no doubt the details were being sent to Germany to let the war authorities know the capacity of railways to carry troops.

He said information was also being collected with regards to crops and alterations to telegraph lines by a staff of paid officers.

Seton said these men were being paid anything from £10 to £40 a month.

He also said he knew of a tailor in Edinburgh whose business it was to collect information about British warships in the Firth of Forth.

Seton told his audience that the German spies in Scotland were tasked not with the discovery of political secrets but with the gathering of hard intelligence about British warships, facing the German fleet directly in the North Sea, and with spying out the land in order to inform the Imperial German High Army Command of the best routes through Scotland for an invading German army to take once it had disembarked.

Seton said he would not be surprised to learn that a German spy was present at the Butterburn Hall talk for he knew they did attend such gatherings.

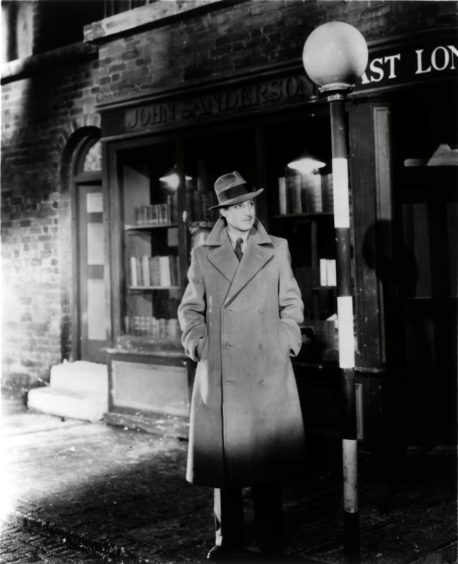

The dramatic tale of spies and traitors might have come straight from the pages of John Buchan’s novel The Thirty-Nine Steps but intelligence expert Anthony Glees said the parallel with Buchan’s page-turning adventure was closer than one might think.

“Sometimes, one’s eye catches a vignette, a newspaper cutting or a picture, a small thing perhaps, yet one which opens the door to a far larger snapshot of history in the making,” he said.

“This 1910 item of Dundee news is one such vignette.

“We read it today obviously set against the backdrop of the First World War which broke out just four years later, but it tells us so much more than one might think at first glance.

“Hidden within this wee feature is the fascinating story of how in 1909 (the year before the talk) Britain acquired, for the first time, a secret service which later became MI5, MI6 and GCHQ, and why the political leaders of the time, who did not much like the idea, in the end bowed to public pressure and agreed to it while insisting it remain one of Britain’s most important state secrets.

“The dramatic talk in Butterburn Hall in Dundee given by ‘Colonel Seton’ seems designed to put the fear of God into the normally sober folk of that city with a tale of a highly dangerous German spy network operating full-pelt out of Scotland.

“What a great line it was to suggest at least one spy might actually be in the audience!”

Far-fetched

Professor Glees said the idea that the Germans were about to land in Leith and Dundee and effectively take out Scotland, having first sabotaged warships, harbours, ship building and arsenals, “seemed far-fetched in the extreme”.

He said: “The need for a counter-espionage agency was initially pooh-poohed by the then British government led by Asquith and the cash for one denied.

“Yes, in 1897, the Reich’s Chancellor von Buelow had directly threatened Britain with the demand that ‘Germany be given its place in the sun’ (at the expense of the Empire).

“But Britain’s leaders said repeatedly that they did not think Germany was any immediate threat.

“After all, Britain was wealthy, already ruled an empire on which the sun never set, and was protected by the Royal Navy, a sea force of unparalleled strength.

“Germany was different, a land power, unified since 1871 following its massive onslaught on France, and ruled by the Kaiser who was the cousin of the King of England and grandson of Queen Victoria.

“No one truly wanted a war so there would not be one.

“Yet behind the scenes, a small number of people fully shared Seton’s concerns.

“Some were in the armed forces, others were influential journalists and novelists.

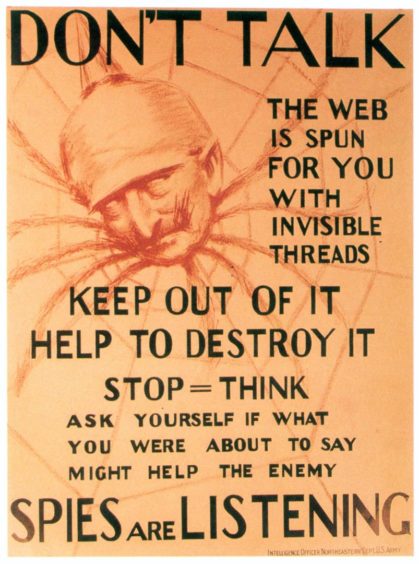

“They were convinced Germany was spoiling for a fight, and had an ‘extensive system of espionage’ in the UK.

“We, however, lacked an organisation to watch, or deter it, and so it was their duty to inflame public opinion to get the government to act.

“Hence Seton’s lecture.”

International expert

Professor Glees, from the University of Buckingham, is recognised as a nationally and internationally published expert on European affairs, the British-German relationship and Security and Intelligence questions.

He said: “What Seton did not tell his audience was that in 1909, the previous year, the British government had finally decided to address the alleged dangers of German spies, and under Lord Haldane (who thought it was a waste of money) had established a ‘Secret Service Bureau’ to uncover and root out the German spy networks in Britain.

“It was this bureau that over the next decades gradually split into two discrete agencies, MI5 and MI6, and then into a third one, GCHQ, with whom we so familiar today.

“Perhaps Seton did not mention this fact because he was not aware of it.

“The existence of the Secret Service Bureau was one of the most closely guarded secrets of its time – indeed, the existence of MI5 was not publicly avowed until 1989 although most people knew such a service existed by the late 1920s.

“It is entirely plausible that Seton was trying to win public support for government action that had in fact already been carried out.”

Unquestioned

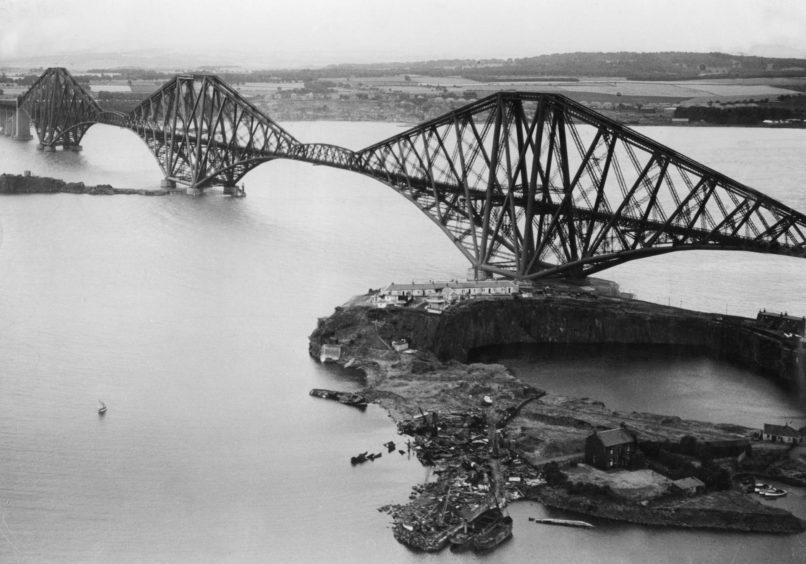

Professor Glees said the strategic importance of Scotland and Scottish harbours and waters for the safety of the British Empire, protected as it was by the Royal Navy, could hardly be exaggerated.

He said: “Control of the North Sea by our Fleet was unquestioned.

“If people did not know there was a counter-espionage agency at work, they could all too easily assume it was vital to have one.

“Indeed, it was very small, basically two men and a dog (the men were Commander Mansfield Cumming RN, who became the ‘C’ of MI6 and Army Captain Vernon Kell, who became Director General of MI5) and even if the public had known, they might not have been much reassured but it was better than nothing, which is what they assumed they had.

“If Seton was drumming up spy mania to get a secret service he was, then, one of those contributing to the widespread, deep public anxiety that the British state was not taking the German threat seriously.

“In the forefront of the campaign to address this were journalists and above all novelists.

“In 1871, in the aftermath of the defeat of France, a short story entitled The Battle of Dorking had gained widespread popularity (it described how the people of Dorking woke up one morning to discover their town had been occupied in the night by Prussian troops) and it led to a flood of similar fiction, including Buchan’s Thirty-Nine Steps and in particular novels written by William Le Queux.

“His Spies of the Kaiser published in 1909 claimed Britain was ‘awash with spies’; another book Invasion 1910 was published in 1906.

“It sold more than a million copies and suggested the Kaiser was planning to invade in that year, using Zeppelin flying ships to destroy the Royal Navy from the air to allow the Prussian Army to be landed safely and begin the military occupation of Britain.

“But it is also possible that Seton may have known more than he was letting on.

“Even though the existence of a Secret Service Bureau was a closely guarded secret, it was still seen as critical by those who had demanded one to garner ongoing public support for its security work, not least to ensure government funding for an increase in the size of the counter-espionage effort.”

No mention

Professor Glees said the question is therefore begged whether Seton himself might have been working for the Bureau.

In neither of the two official histories of MI5 is there any mention of a ‘Colonel Seton’.

“However, we are told by Professor Christopher Andrew in his authorised history that in the summer of 1910 Captain Vernon Kell visited Scotland to speak to gatherings about the spy threat and to put pressure on the chief constables of Scotland to produce a secret register of Germans in Scotland, to be arrested and interned in the event of hostilities between Britain and the German Reich,” he said.

“Is it possible that Seton was Kell?

“In theory, ‘yes’, most certainly.”

Kell’s efforts in Scotland bore fruit.

In 1912 a German, Karl Graves, who had set up as a locum doctor in Leith, was suspected of being a spy and arrested (Kell personally went to Glasgow to take charge of the operation).

Later in Barlinnie prison, Grave disclosed the existence of a German plan to blow up the Forth Railway Bridge.

Graves later wrote a book based on his experiences as a spy, which was published the day before the war started.

Because of the perfect timing, Graves made a fortune and became perhaps the most well known spy worldwide.

He had additional brushes with the law later on, including burning a woman alive and being locked up for fraud.

Final twist

There is, however, one final twist in the tale.

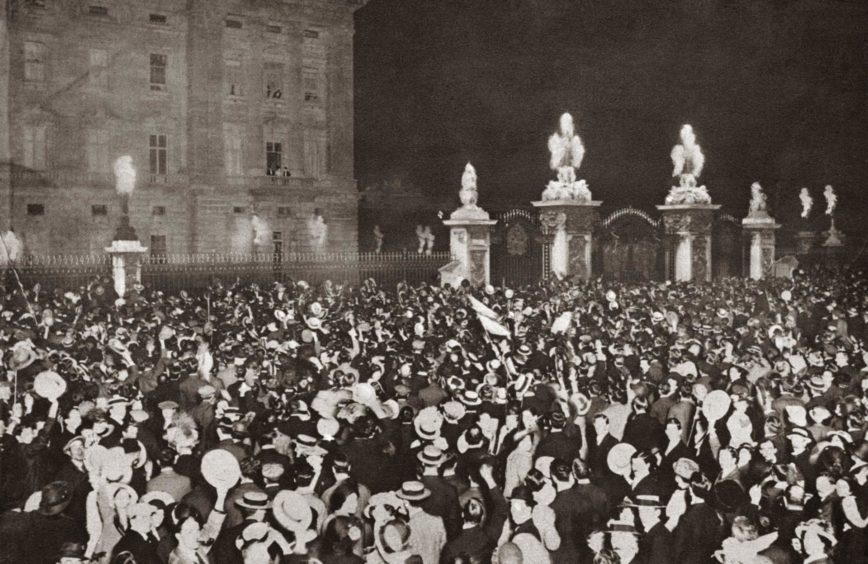

On August 4 1914 Britain went to war against Germany and in parliament on August 5, the Home Secretary announced to widespread public enthusiasm that 21 German spies had been arrested “all over the country” in the past 24 hours, many of them in “important naval centres”.

Professor Glees said the speed they had been apprehended implied the government had known exactly where to look for German spies and saboteurs and that they had done very well indeed.

The public were reassured and within the hidden recesses of the British state, the Bureau was applauded.

It had been successful, it seemed, and all was well.

However, the government never disclosed how many of those arrested had actually been spies, and how many of them were simply ordinary Germans who had come to the UK to work.

Sadly, perfectly decent and innocent Germans were attacked by mobs prior to their being interned ‘just in case’.

Political purposes

Professor Glees said: “The suspicion today was that most of the 21 were not spies but were simply being used for political purposes and it is apparently well-founded.

“The government wanted to be seen as effective, unfortunate Germans may have paid the price.

“The Germans did indeed run a naval espionage network in Britain (but not an army one).

“Equally, the Germans believed Britain ran a spy network in Germany but it did not; they also believed Britain had a security service long before 1909.

“Within four years of the Butterburn Hall talk in Dundee, Britain and Germany would be at war, locked into the most devastating conflict in history, in which 17 million people were killed.

“In 1910 such a dire thought would have seemed so far-fetched as to be beyond even the spy fiction that so many loved to read.”