The story of eccentric hot air balloonist James Tytler is a movie maker’s dream. Gayle Ritchie charts the life and legacy of the “bungling” Angus-born aviation pioneer – a man who fell from grace and ultimately became a laughing stock.

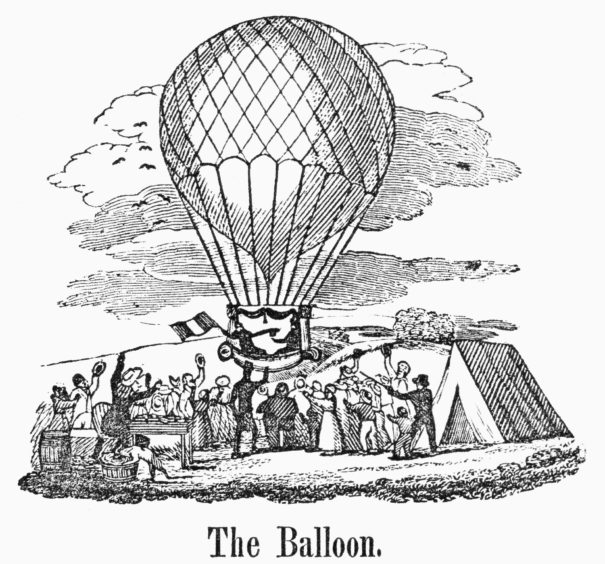

As the hot air balloon soared up into the air, reaching the heady heights of 350ft, the crowd below roared a loud huzza.

It was a hot summer’s day in 1784 and a spectacle such as this had never been witnessed in Britain.

Balloonist James Tytler, clinging on to the wicker basket for dear life, raised a hand to wave to his adoring fans and grinned from ear to ear.

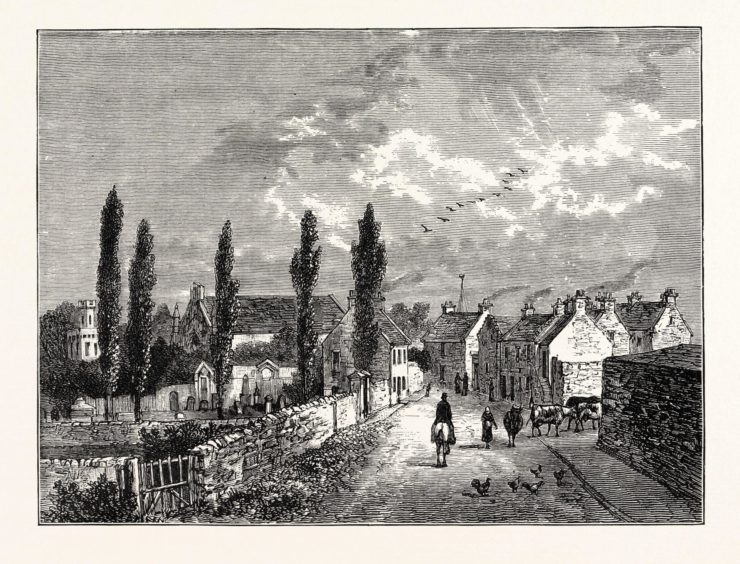

His balloon was airborne for 10 minutes and travelled for half a mile over Edinburgh, coming to rest on a road in the nearby village of Restalrig.

Angus-born Tytler was hailed a hero.

Pride before a fall

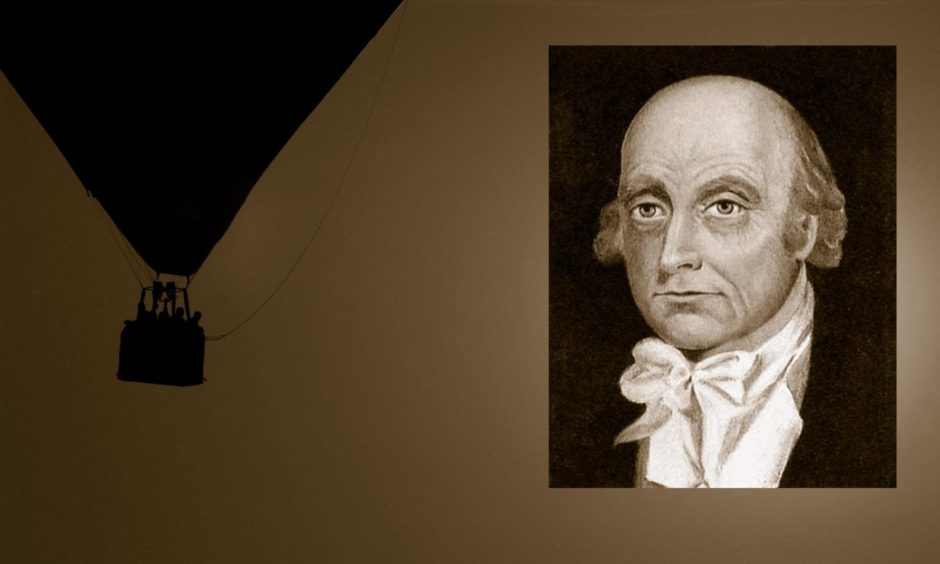

Born the son of a minister in 1745 in Fern, Forfarshire – now known as Angus – Tytler’s life was one of many ups and downs.

He managed to claw his way out of poverty to study medicine at Edinburgh University before heading to sea to work as a doctor.

He never made it as a surgeon and returned to the capital to become a pharmacist in Leith.

Alas, he ran up huge debts and fled with his wife to England to escape his creditors.

When the coast was clear, Tytler returned with his wife and children and took up writing to make ends meet.

Under the pseudonym “Ranger”, Tytler published Ranger’s Impartial List of the Ladies of Pleasure in Edinburgh, a private book detailing 66 working ladies in the city.

In 1777, he became editor of The Encyclopaedia Britannica where he learned of hot air ballooning and the first-piloted ascent by the France-based Montgolfier brothers in 1783.

It was then that Tytler had a lightbulb moment. Could he, as a man who had witnessed so many failures, be the first to successfully emulate such aviation adventures in Britain?

“He set about constructing his very own ‘Grand Edinburgh Fire Balloon’ with very little money and probably even less public support,” says Edinburgh-based historian and Tytler fan Robert Murray.

“He charged 6d to see a model, and eventually had his balloon ready for a public inflation, though not for a flight.”

Up, up and away

Tytler’s early attempts to get up, up and away were slightly woeful but he refused to give up.

He advertised his first public ascent, to be held at Comely Gardens, on August 6 1784.

Needless to say, this attempt was dogged by technical problems and the weather.

“The press attacked him, and the mob attacked his balloon,” says Robert.

“Discouraged but not beaten, he was ready again towards the end of the month.”

On August 25, his balloon rose just a few feet from the ground.

According to the Edinburgh Evening Courant: “The balloon, together with the projector himself, and basket in which he sat, fairly floated.”

Two days later, however, he had even greater success, “navigating the atmosphere” for about half a mile to the nearby village of Restalrig and reaching a height of 350ft.

Tytler was famous. He was lauded as a national pioneer – the first Briton to defy the laws of gravity – and the first to fly a hot air balloon in the country.

Buoyed up by his success, Tytler started to charge the public a small fee to watch.

A mockery

Much to the disappointment of his new fans, later trials were less fortunate.

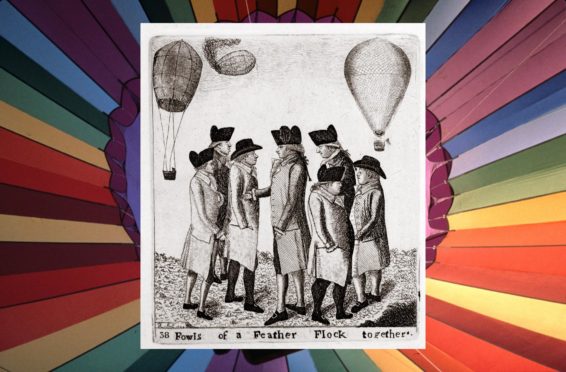

When his efforts failed, he became a laughing stock, the press deriding him and his “bungling, misshapen, smoke bag”.

In October 1784 his balloon only took off after Tytler left the basket.

Having previously been “the toast of Edinburgh”, he was mocked and called a coward.

His very last flight was on July 26 1785.

When his efforts failed, he became a laughing stock, the press deriding him and his ‘bungling, misshapen, smoke bag’.

Tytler was soon overshadowed by Lunardi – the self-styled “Daredevil Aeronaut” – who carried out five sensational flights in Scotland, creating a ballooning fad and inspiring ladies’ fashions in skirts and hats.

Mired in misfortune

His misfortune continued with complete bankruptcy and then his first wife Elizabeth Rattray sued him for divorce.

Tytler ended up in Salem, Massachusetts, where he edited the Salem Register, published some works and sold medicine.

His body was found on the shore there on January 9 1804. He had left home drunk, fallen into the water and drowned.

In Edinburgh, a small street called Tytler Gardens near Holyrood pays tribute to the quirky character.

Movie material

Perth historian Dr Nicky Small believes Tytler is a “really fabulous character” who deserves to be remembered as a man of many talents – and she reckons his life story is is a film maker’s dream.

“I think his story would make a great movie,” she says.

“It has everything from modest beginnings to unsuitable marriage and a pioneer turned disaster!”

Dr Small, who is a local history officer with Culture Perth and Kinross, is also a talented musician and part of PlaidSong which combines historical subjects and traditional music.

“I think Tytler’s story might just inspire a song!” she says.

“He was a really unlucky person. A book on Tytler by Sir James Fergusson details all the previous biographies about him and outlines contemporary reports on Tytler’s life and work and he tends to use the word ‘unlucky’ so often.

“He was quite adventurous and actually took to sea in a whaler when he was 19.

“When he returned he was married very young and went on to have quite a number of children by three partners – and he enjoyed a drink!

“His personal situation and providing for his family meant they were always on the poverty line.

“Fergusson states that he could be industrious and had an eye for projects or up-and-coming ideas but had no sense of business – he rarely profited from his work.”

When it came to ballooning, Tytler grasped the opportunity to explore the “new phenomenon” and moved forward with bold plans to create and launch one, says Dr Small.

“That was remarkable given his lack of funds and yet he advertised his experiments in newspapers and must have talked publicly about his ideas,” she says.

“It was such a grand vision – to be the first to ‘navigate the air’ and to actually carry this out, almost.

“He did carry out his various attempts but seems to have misjudged lots of the science – his calculations around what a balloon would carry and obviously he had no way to control it.

“He admitted later at one point he did not want to be seen to be a coward about not going into the basket below but the weather was an issue and strong winds really hampered his efforts.”

“What is astounding is that the public and the press hailed him as a national pioneer but had no patience with him as his efforts failed and then they quickly derided him when things went wrong,” says Dr Small.

“Some time later the balloon was recalled as having risen ‘over a dyke, and then quietly settled on a midden’. I like to think he did a bit more than that!

“There were great crowds and great excitement around what might happen and people were certainly hoping to see something remarkable.

“It was undoubtedly a balloon flight, but too short for any observations of value even if Tytler had taken any instruments up with him and not been too excited to think of anything but the enjoyment of his triumph.”

“His death by falling into the sea at night while drunk is almost what you might expect given his chaotic life, its ups and downs and his eccentric ways.”

A place in history?

While Tytler clearly played a role in aviation history, his name is little known.

“He was right there at the heart of things, but he’s always on the periphery of any history,” says Edinburgh historian Robert Murray.

“Although he was the first person in Britain to fly, he doesn’t always get that credit.

“He was a highly unusual character, and the Grand Edinburgh Fire Balloon episode is typical.

“How many people would have researched this new thing called ‘‘aerostation’ (the art of raising and guiding balloons in the air), thought, ‘I could do that!’, and then actually gone ahead and done it?

“That he could triumph against all probabilities, become a popular hero, then almost immediately throw that away, is typical of his life’s endeavours.

“He had some aspect of his character that seemed to guarantee that every skill and every success left him with nothing.”

Extract from Balloon Tytler by Sir James Fergusson

Friday August 27, 5am

The balloon was hoisted up and the fire underneath kept burning strongly for nearly an hour until the balloon was well filled and pulling at its ropes with great force.

Tytler felt certain it was capable of lifting half a ton.

The favourable moment had come at last. Once more he took his seat in the little basket and the securing ropes were released.

Up shot the balloon and its passenger, but only to be immediately checked, partly by a rope and partly by the branches of a tree. Cleared of these obstructions it finally soared into the air.

The spectators raised a loud huzza. Tytler waved his hat.

He rose to a height of 350ft, as measured by a cord left hanging from the basket and might have mounted higher but for the check at the balloon release and the alarm of some of his people on the ground who caught hold of the trailing cord.

But the balloon’s strength was enough to tear it from their hands and the breeze wafted Tytler northwards over the slight rise of Abbey Hill and on for about half a mile from Comely Bank.

Then, as the air within the envelope cooled the balloon sank gently downwards and touched ground on the road to Restalrig.