He is a man who has rubbed shoulders with some of football’s greatest names, including Jock Stein, Franz Beckenbauer, Pele and Gerd Muller.

And he took part in a match in Saigon during the Vietnam War where he spotted a chap with a device for detecting land mines loitering close to the penalty box.

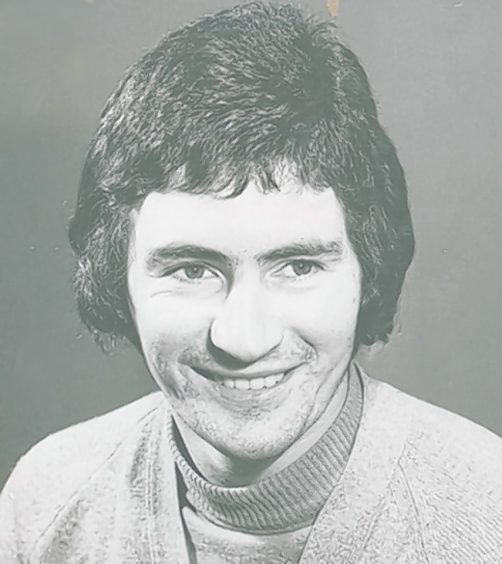

That was one occasion where Jack Reilly, the Stonehaven-born goalkeeper who ventured Down Under via the circuitous route of a north-east schools league, Hibernian and then the Washington Whips in New York, decided discretion should be the better part of valour.

But, throughout the rest of his remarkable career, which featured a series of appearances at the 1974 World Cup in West Germany, this blithe fellow, who has never been afraid to speak his mind and damn the consequences, has become a wizard of Oz, both on and off the pitch, and a formidable business figure whose powers of persuasion and knack for negotiation helped set up the A-League and bring Manchester City to Melbourne a few years ago.

Easter Road

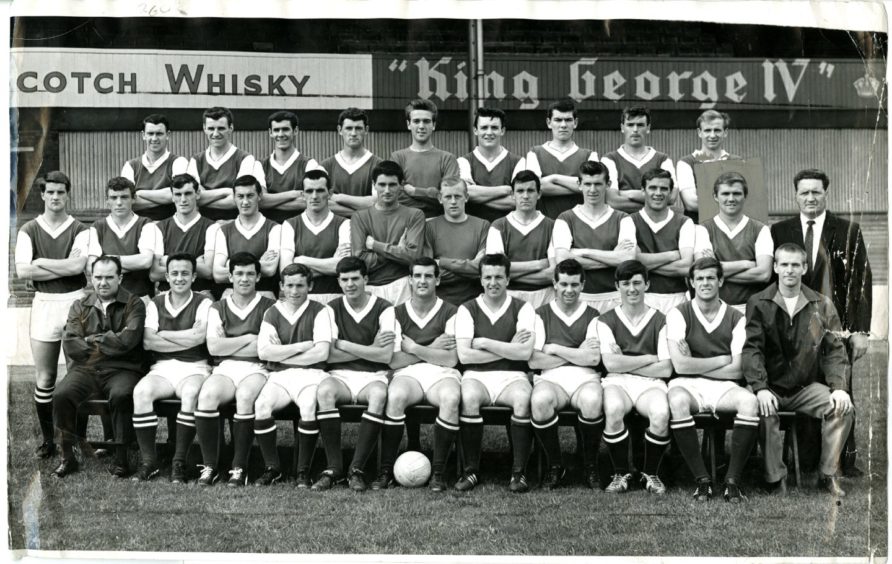

It’s not bad for the youngster who learned his goalkeeping skills while playing with Aberdeenshire sides Parkvale in his home community and Inverurie Loco Works, prior to taking the step up to Easter Road in the early 1960s.

At that stage, he was the apprentice plying his trade between the sticks, but soon enough, Reilly proved his worth as a global traveller during a series of remarkable exploits.

He may not be celebrated by his compatriots, yet the 77-year-old is an esteemed personality within the Australian football community, who can empathise with his single-minded dedication, and appreciate the sacrifices he made as a youngster after his father – a paratrooper – was killed in France during the Second World War.

It was a tragedy which might have floored others, especially somebody who never even saw his dad before the latter had gone.

But not the little kid with the big passion for picking up his boots and running to the local park.

At the age of just six, he was put through his paces on the wing for a juvenile team in Stonehaven, but their coach, a local undertaker with a lugubrious temperament, had been a goalkeeper in his own youthful days.

And, 40 minutes later, so was the new boy.

A bright lad o’pairts with an interest in school, where he demonstrated signs of the acumen which later led to him becoming a successful business figure and administrator, Reilly had no desire to burn his boats without gaining a proper education.

He was 20 before he was signed by Hibs and even then, he spent much of his time in the reserves, appearing in just 10 senior matches.

Jock Stein

Reilly said: “He was far and way the best manager of people I have ever seen.

“When there were problems, he always spoke to the players involved directly. He didn’t listen to club gossip and, most of the time, he came up with the right solutions.”

The latter quality wasn’t lost on Reilly himself, who has been an innovative figure wherever he has journeyed.

At the age of 24, he headed to the US as part of the new attempt by American officials to create an attractive competitive structure.

The initiative also included Aberdeen and Dundee United’s squads who participated in a series of contests across different cities with the Dons finding themselves rebranded as the Washington Whips and the Tannadice side as Dallas Tornado.

He received a lucrative contract, but was torn by the prospect of having to leave behind his mother and grandfather – “It was very, very hard, but a decision had to be made” – and yet, once again, he refused to take the easy option.

A transatlantic mission beckoned.

Not for the first time, the expensive American experiment failed to have the desired effect in preaching to the unconverted, but while he was in Washington, Reilly locked horns with the peerless Brazilian legend Pele.

And how he revelled in the memory.

As he subsequently told the Sydney Morning Herald: “He had a greatness of vision. He would search the field to see what could be done with the ball before it arrived – and then he had the skill to do whatever he wanted.”

Halcyon days

These were halcyon days for the peripatetic Scot, who was still in his mid-20s, and had lost none of his wanderlust and desire for fresh challenges. When he moved to Australia at the end of the decade, he was a big, bold, beguiling presence in goal for Melbourne Juventus and his performances were swiftly noticed by officials at the highest level.

As one of his colleagues declared: “He looked like a class player from the first few days. And it wasn’t a surprise when his reputation rose almost every game he played.”

Soon enough, he was as hot as the Australian outback. And he was drafted into the Socceroos squad for a world tour. Meanwhile, his transfer from St George Saints to Melbourne Hakoah in 1972 for a then-record fee of $6,000 attracted major headlines in a country where most of the attention was focused on cricket, rugby league and Aussie Rules.

Lavish applause

The scale of their achievement in qualifying should not be underestimated – there were only 16 teams (including Scotland, who were eventually eliminated without losing a match) at the 1974 event and they had to tackle both West and East Germany and Chile with few observers giving them a prayer.

However, despite their campaign ultimately finishing in disappointment with Rale Rasic’s squad losing two tussles and drawing 0-0 with Chile, Reilly and his side not only enhanced their standing on the global circuit, but earned lavish applause from the home supporters – a sign of the progress which was made by the underdogs.

As Australian journalist Martin Flanagan stated: “Australia played the host nation and eventual winners West Germany and that was the best moment of Reilly’s career, walking out into a packed stadium in Hamburg to face a team that included champions such as Franz Beckenbauer, Gerd Muller and goalkeeper Sepp Maier – names we had just dreamt of.

“Australia lost 3-0, but they had their chances and they played with spirit. For the last 15 minutes of the match, Reilly fondly recalls that the German crowd supported them.”

The denouement also sparked a near diplomatic incident when Reilly was desperate to collect the jersey worn by his illustrious opposite number.

As he recalled: “I couldn’t get to Sepp quick enough to get the jumper off his back.

“I was yanking it and yanking it and he was yelling: ‘dressing room, dressing room’. Then, he was taking it off and I almost castrated the poor guy.”

Sacked

If that was over the top, there was nothing restrained about the reaction of the Socceroos when they returned home and were told on the airport tarmac by the president of the Australian Soccer Federation, Sir Arthur George, that Rasic had been sacked in absentia.

The players were incandescent as such shoddy treatment being doled out to a man who had steered Australia to previously uncharted heights.

And Reilly was among the angriest.

Indeed, he said recently: “I blame that (decision) for the fact that it took us another 32 years to qualify for the World Cup again.”

After winning 35 caps, he moved into the administrative ranks, but Reilly has never been a stuffed shirt or a fossil-fuelled member of the blazerati.

On the contrary, he poured his heart and soul into his beloved pursuit, whether as chairman of the Victorian Soccer Federation, or the Carlton club, or being a catalyst for the A-League and who still travels thousands of miles every year in his eighth decade.

Stein philosophy

There is something of the Stein philosophy about his attitude that the sport lives or dies on the efforts of the players at the coal face and the fans who pay their admission money.

He said: “I love the game because of everything that it has given me. I always wanted to be a footballer and I got the rewards of the game.

“Now, I want these rewards to be available to others.”