A gripping eyewitness account of the day a wartime mine exploded in Stonehaven Harbour, “shattering” the old town, has been shared for the first time.

Hugh Ramsay, who was an 11-year-old Boy Scout on that dramatic day in November 15 1944, has recounted his vivid memories of the fear and devastation caused when the blast ripped off roofs and shattered windows as fearful families cowered in a safe refuge.

“It was about 8pm when the whole town was rocked by a huge explosion, the mine had been driven against the harbour wall, just under the Ship Inn. We all knew this was bad, very bad,” recounted Hugh.

The drama had started earlier when Coastguards saw a drifting mine, torn loose from the huge minefields between Scotland and Norway, said Hugh, now 87.

Mine drifted towards harbour

Because of the high seas it was left alone as it was not an imminent danger, but strong winds sprung up, sending the mine towards Stonehaven’s Harbour.

Hugh recalled: “We all rushed down to the old town as the news spread, and we could all see the mine quite clearly drifting past Downie Point.”

As the mine came ever closer, the people of the old town were told to evacuate their homes and take refuge in Mackie Academy, which these days is the town’s Arduthie School.

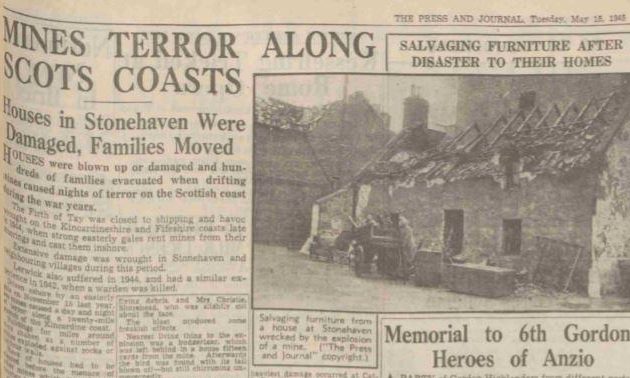

The P&J from May 15 1945 – after VE Day and when wartime reporting restrictions were eased – gave an account of the incident, headlined: “Mines terror along Scots coasts”, including the hurried evacuation.

“Many housewives had to leave their husbands’ midday meal ready in the pot,” it said.

“Some of them went to Bervie Braes, overlooking the harbour, to watch the mine tossed about in the water in front of their homes.”

Felt very important

As the refugees arrived at Mackie Academy, Hugh was one of the Boy Scouts given the important job of registering folk as they arrived at the school.

“We felt very important in our uniforms, short trousers of course, with our clipboards greeting the ladies and kids,” he said. “We were quite excited about the whole thing as young lads.

“I remember quite clearly a lady pushing her pram up from the old town, she came to the door out of breath and exhausted. I said: ‘Is it you and the baby?’ She replied: ‘Oh wait a minute’ and she pushed back the pram covers. There was this huge black and white cat, called Peter, sitting there quite calmly.

“We were confused because we weren’t sure if cats could be registered or not.”

Slowly the anxious hustle of registration gave way to relative calm, with food in the dining hall and bunk beds, with grey army blankets, in the gym, recalled Hugh.

“It was warm and cosy inside. Outside the wind still blew a gale, the adults’ coats dripping wet, hung from the kids pegs, trailing wet puddles over the stone floor. By now the old town was a no go area, sealed off by the police,”

Shattered by noise

Then the tense waiting game began. At 8pm a deafening roar shook Stonehaven.

“All of a sudden, it happened,” said Hugh “There was this great big noise from the explosion – the whole town was just shattered by this noise – then suddenly silence in the school. People knew this was terrible. People started to cry because they knew their homes could be in danger. We were stunned.”

Eventually the police arrived to deliver the bad news. Roof tiles had been ripped off, windows were smashed and two boats had sunk. There was devastation in the harbour area.

“The whole of the old town facing the sea had been completely smashed to pieces,” said Hugh.

Even Hugh’s father’s shop – the town’s iconic draper Hugh Ramsay Ltd – had three plate glass windows blown out in the Market Square.

“He had to get a joiner to put up boards on his window.”

Freakish results of explosion

The P&J reported one house on the Shorehead was wrecked and roofs were blown off several others, sending slates and tiles flying over a distance of more than 200 yards. People standing in the High Street were thrown off their feet, but apart from three people who received cuts there were no casualties.

The report said: “The blast produced some freakish results. In the Marine Hotel a big porcelain rum jar disappeared. A similar size jar sitting on a shelf beside it was untouched. Only a few glasses on the bar were broken, although all the windows in the building were blown in, in a hail of splinters, into the furniture and walls.”

The mirror behind the bar of the Marine still bears the scars of that mine damage to this day, with a network of scrapes, scratches and gouges on its surface.

Perhaps the oddest story to come out of the devastating blast revolved around a beloved family pet.

Explosions in the night

The P&J reported: “Nearest living thing to the explosion was a budgerigar, which was left behind in a house 15 yards from the mine. Afterwards the bird was found with its tail blown off – but still chirruping unconcernedly.”

The harbour mine was not the only one to have drifted ashore over those “nights of terror”. One had beached near Turner’s Close at the High Street, another threatened Allardice Street, according to the P&J, while another washed up near the Bridge of Cowie.

While there were explosions heard during the night, none of the other beached mines blew up, said the P&J.

Hugh recalled: “Peter the cat slept soundly covered in prams blankets. I never slept a wink, I could not wait to get down to the old town the next day to see the damage for myself.

“I went down and just saw this total destruction. There were tiles everywhere, glass everywhere, bits of wood everywhere. It was destruction on a scale we had never seen before.

“People were quickly allowed back into the town, but a lot of people couldn’t stay because their houses weren’t habitable. Workmen started clearing the town and very quickly some semblance of order was worked out.”

The terrifying events had a lasting impact on the people of Stonehaven, the topic of conversation in the days, weeks and months after.

Wartime came to Stonehaven

“There was a just a general air of bemusement. Nothing like that happened before,” said Hugh.

“We knew it was wartime, but wartime hadn’t affected Stonehaven at any time at all, until this happened. Suddenly it dawned on us that this was part of wartime Stonehaven and we had to accept it. For us, as young lads, it was quite an experience.”

Hugh went on to take over his father’s shop, a Stonehaven institution, running it for many years as a director until he retired. He was the fifth generation to run the company. It is now the Co-op in the Market Square.

While he followed his father into the business, Hugh had early ambitions to be a reporter but it was not to be. His love of writing is, however, one of the reasons he penned his account and has now shared it online, after recently receiving a new tablet. It has generated a lot of interest.

“Lots of people have mentioned their relatives being affected by this… and I even got a reply from Australia.”