It’s 65 years since Dundee aviation pioneer Preston Watson’s habit of killing seagulls and conducting trials on their corpses was exposed. But was this a cruel act or a necessary evil which ultimately helped saved millions of lives?

The story of Tayside aviation trailblazer Preston Watson is surrounded in myth and legend.

Some claim he beat the famous Wright brothers into the air by five months in the summer of 1903, while others believe there is no evidence for such a feat.

One thing Watson did do, however, was to conduct experiments on seagulls.

He would shoot them from the sky with a shotgun, attach weights to their bodies, adjust their wings and tail feathers and launch them from a railway bridge in Dundee.

He would then observe the dead birds as they glided and ultimately crashed to the ground.

In the December 1955 issue of Aeronautics magazine, Watson’s younger brother James recounted that: “Before the last century Preston studied the flight of gulls, caught many of them, put small weights on their heads, glued their wings into the position he wished, and was frequently seen by passers-by dropping them over the road bridge, which crossed the railway line at the west end of the Dundee Esplanade.”

It was James who also claimed his brother – who was obsessed by all things aeronautical from an early age, constructing model gliders and experimenting on captured birds – had beat the Wright brothers into the air.

Retired hospital consultant Alastair Blair, from Fife, penned a book, The Pioneering Flying Achievement of Preston Watson, in 2014.

Written in conjunction with engineer Alistair Smith, it explores Watson’s life and legacy.

“Watson weighted the birds with lead pellets, then adjusted the wings and tail feathers in various arrangements and launched them off the Ninewells bridge,” said Blair.

“I think his main preoccupation was how to set the wings to make them glide straight and level and probably to work out how to achieve a flight path of a gentle curve.

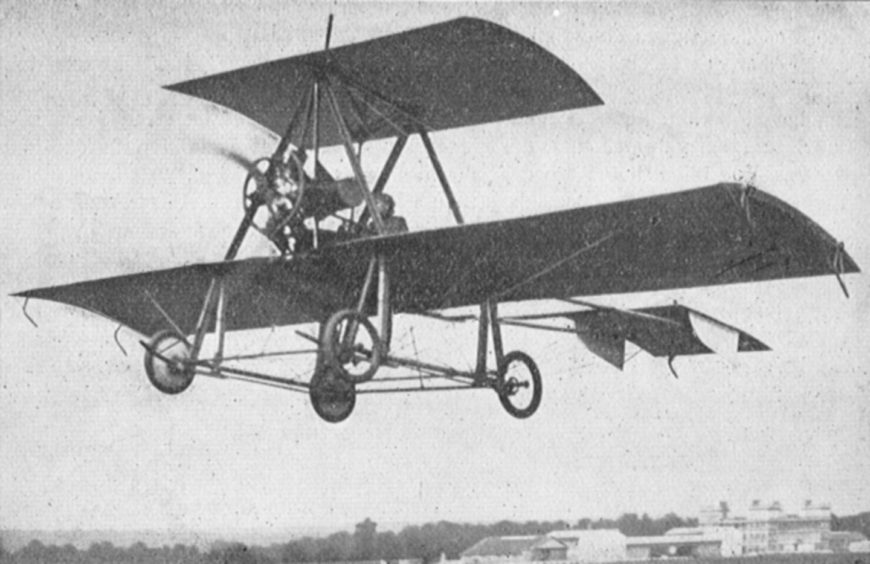

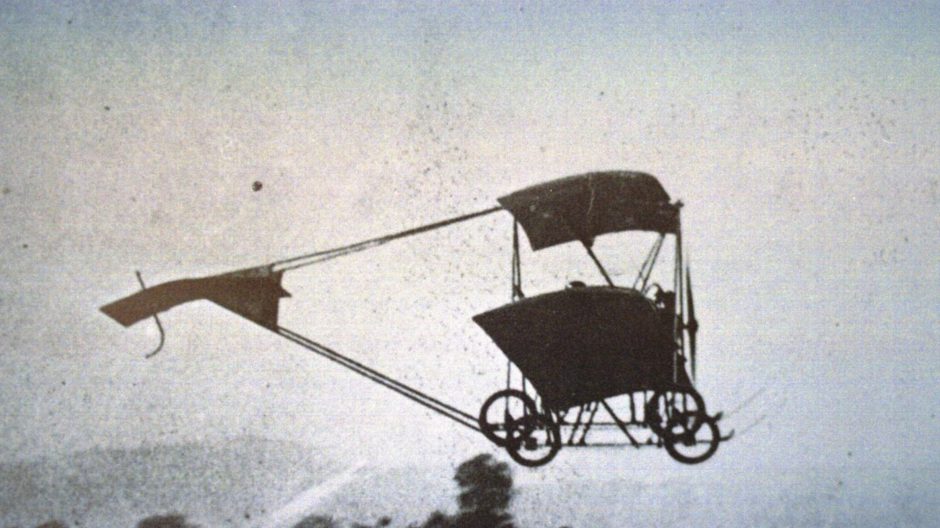

“It was these experiments that guided him in the construction of his first flying machine – a glider which he later fitted with an engine.”

Blair said Watson was “first” to achieve this in his first plane which he fitted with a rocking wing.

“Up to this point it was thought that aircraft should turn in a horizontal plane,” he added.

“The Wright brothers never satisfactorily solved the problem and finished with a cumbersome arrangement operated by the pilot’s pelvis.

“I think Watson used his observations of birds on the wing to prompt a proper experimental approach.

“Quite apart from the cruelty it would involve at the end, either the bird or Watson would not survive. And seagulls are very strong and very savage!”

Eyewitness accounts, including some published in The Courier, indicated that Watson achieved a series of powered “hops” in the summer of 1903.

“Was he the first to fly? However one cares to define ‘fly’, the answer is probably ‘no’,” said Blair.

“If any convincing ‘hop’ is taken as the definition, then he was certainly not the first.”

Quite apart from the cruelty it would involve at the end, either the bird or Watson would not survive. And seagulls are very strong and very savage!”

Alastair Blair

Blair said Watson’s trials weren’t the only ones which resulted in loss of life.

“One poor fellow built himself a pair of wings and jumped off the Eiffel Tower. Fatally.”

Sporting sacrifice

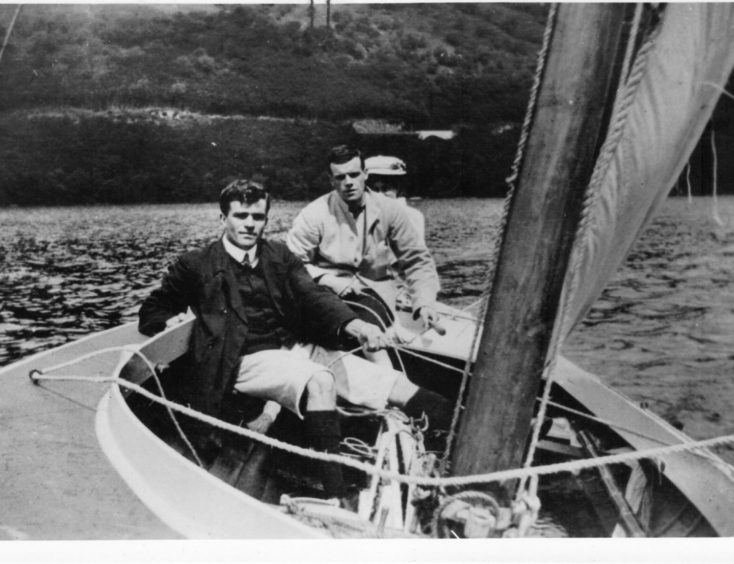

Budding athlete Watson even forsook training sessions with friends to contemplate seagulls flying.

“I imagine that would be when he was about 18,” said Blair.

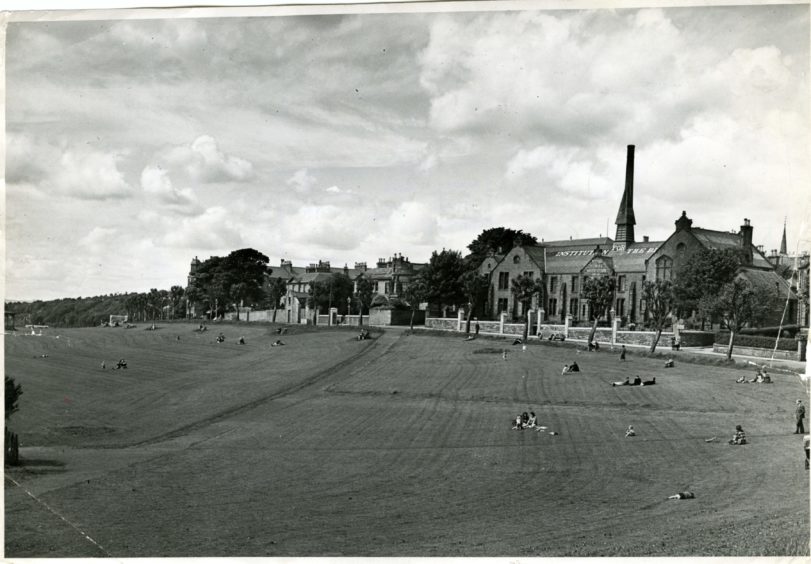

“The family moved house around that time from Magdalen Yard Road to a large house further out towards Ninewells. Both these were very close to Magdalen Green and it is likely that the informal sporting activities took place there.

“It was adjacent to the River Tay and seagulls were plentiful.”

He would sit on Dundee Esplanade’s wall, close to the railway bridge, watching seagulls in flight while his Newport Rugby Club team were busy training.

A friend asked why he was just sitting there instead of training with the others.

Watson apparently told him: “One day we are going to fly, just like these gulls,” only to be chided by his brother James – later his great aviation ally – and friends for an idea that was “just daft”.

CV

Born in Dundee on May 17 1880, the son of a wholesale food distributor, Watson was a pupil at the High School and showed considerable interest in all things mechanical from an early age.

He studied physics at the city’s Queen’s College and began building his own aircraft.

Encouraged by the success of his series of powered “hops” over Errol in the summer of 1903, Watson went on to build two further planes.

He joined the Royal Flying Corps at the outbreak of the First World War.

He was killed in a flying accident in 1915, at the age of 34, and is buried in Dundee’s Western Cemetery.

Cruel?

Many people argue that Watson’s trials were worthy ones – they were trials that reliably informed the aviator’s research and ultimately saved millions of human lives.

Others find the concept of killing seagulls to be abhorrent.

Award-winning Exeter-based photographer Jenny Steer is one such person.

She is working on a photographic project about her love for gulls and has a website, iloveseagulls.co.uk, dedicated to the birds.

“Humans have done some terrible things to animals and many in the name of progress and to save humans,” she said.

“I’m of the opinion that all sentient beings deserve to live out their lives in the best way.

“Humans put themselves at the top of the list as being the most important.”

Menace of “rats of the air”

Dundee’s relationship with seagulls has been well-documented, with recent reports of people having food ripped out of their hands or being attacked by the birds.

In July last year, there were reports of gulls preying on young ducklings at the Swannie Ponds.

Many people now refuse to eat outside in the city centre as they fear they could be the next target for the scavengers.

Last year it was claimed the council was fighting a losing battle against the rising numbers of the birds, which appear to be getting more aggressive.

But what is the solution?

Do we live and let live, should we be trying to reduce the amount of litter attracting the birds, or should, as some have suggested, there be a cull of gulls, despite them being a protected species?

- The Pioneer Flying Achievements of Preston Watson by Alastair W. Blair and Alistair Smith is available on Amazon and is due back in stock at Dundee Museum of Transport. dmoft.co.uk