Dundee jute workers in Calcutta dodged Japanese bombers and shark-infested seas to get back to Blighty during the Second World War.

Dundee’s links with India and the jute trade remain an integral part of life for a lot of people from this area.

Ambitious jute workers moved from Dundee to Calcutta in the 1850s, and they ran the myriad of mills along the Hooghly River for the best part of a century.

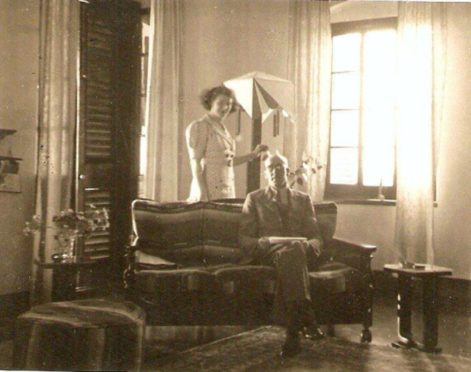

Kenneth Miln

Monifieth man Kenneth Miln grew up in India where his father worked in the sweltering tropical heat after going there in search of a better life.

The jute workers from Dundee imprinted themselves in Calcutta’s being and there is still a cemetery there where more than 3,000 Scots lie among the tombs.

Kenneth said the scorching sunshine of Calcutta seemed a very long way from Dundee although the accents of home could be heard at every turn.

On December 7 1941, the Japanese attacked the US naval base at Pearl Harbor and later declared war on Britain and the United States.

In the days and weeks that followed, the Japanese invaded European colonies across East Asia, including the British territories of Hong Kong, Malaya, Singapore and Burma.

Japanese armies attempted to destroy the Allied forces and invade India in 1944, but were driven back into Burma with heavy losses.

Kenneth’s family lived in the Megna Jute Mill compound where two Lewis guns were mounted on the roof and an anti-aircraft gun was positioned nearby.

“Although the war in Europe was over, the war with Japan still raged and the situation in West Bengal was dangerous,” said Kenneth.

“I can remember hearing and seeing Japanese bombers passing over our compound at Megna and some of these aircraft were shot down near Calcutta.

“On one such occasion my father took me to see the remains of a Japanese bomber, with the remains of the crew still in the cockpit.

“Towards the end of 1944, the ladies of Megna Jute Mill, held a special afternoon tea-party for a number of injured British soldiers on their way back to Blighty.

“Although aged just seven at the time, I can clearly remember taking plates of sandwiches to these men and being frightened by the appearance of some of them.

“A few of the soldiers had sustained severe facial injuries, with metal-clips, wires and bandages covering their heads.

“I can still see, albeit in the minds eye, some of these very brave men.

“It is to their bravery and sacrifice that we, and many other jute-wallahs survived World War Two.”

Impossible journey

During World War Two it was all but impossible for Dundee jute workers who were based in India to take their overseas leave periods back home in Britain.

Up until 1939 it had been standard practice for them to take six months home leave on completion of every three years of service in India.

“By 1945 my parents, John and Betty Miln, had been in India for some 20 years and were eagerly looking forward to a long overdue return to Dundee,” said Kenneth.

“Passages were duly arranged but at the last moment my father had to delay his departure due to mounting political tension in India.

“The situation rapidly became critical with the British Empire’s demise imminent.

“However, in March 1945, my mother, myself and the daughter of a family friend in Calcutta sailed from Diamond Harbour on the British India steamship Valera, which was a small passenger-cargo vessel of just under 5,000 tons, powered by triple expansion steam-engines, from which deep thumping sounds reverberated throughout her hull and even into the cabins.

“The heat was terrific as we sailed down the River Hooghly and out into the Bay of Bengal and slight respite came from the cabin-blowers.”

The ship heaved and swayed down the Coromandel Coast towards Colombo in Sri Lanka where they stopped for a couple of days in the harbour.

Shark-infested waters

Kenneth said: “Our next port-of-call was Aden, an arid sun-baked port set in crystal waters swarming with tropical fishes and sharks.

“Shortly after departing from Aden, members of the crew set-up a huge box-like structure on the ship’s bow which was to house a search light to lead us, by night, through the Suez Canal and on to Port Said in Egypt on the Mediterranean Sea.

“The SS Valera had been fitted with a number of anti-aircraft pom-pom guns which were used on one occasion to fire at targets which were being towed by aircraft.

“It was indeed exciting to see the lines of tracer-bullets arcing up towards the targets and the lifeboat drill was a regular event.

“Security and discipline on board was paramount with no lights at night, cabin porthole covers in place by sundown and cigarette-smoking on deck was prohibited for it was still possible that an attack from an enemy submarine could take place.

“The final and very exciting stage of our sea passage was through the infamous Bay of Biscay when I used to stand holding-on with the helmsman up on the bridge.

“We held on tightly as massive waves of green water swept over the deck and at times it seemed that our ship could not possibly survive such monstrous seas.

“However, we all survived and the Valera docked safely at Southampton.”

London scarred by bombs

They took the train to King’s Cross Station in London and made their way through parts of the city where they witnessed some of the devastation caused by enemy bombing.

“I clearly recall being shocked by the sight of so many destroyed buildings because we never expected London to have suffered so much destruction,” he said.

“After spending around six months in Dundee I returned to India with my mother at the age of nine on the Polish ship Batory which was a vessel of just over 12,000 tons.

“The ship was fully loaded with passengers and troops headed for the Far East and we had a speedy passage across the Mediterranean and back to Bombay.

“We disembarked to catch the overland train to Calcutta and would later learn that we escaped just in time because the Batory had been fired upon whilst in dock.

“On arrival at Calcutta’s Howrah Station, on the west bank of the Hooghly, we were met by my father who escorted us to our mill taxi for an hour’s drive out to the Megna Jute Mill compound which was located some 20 miles north of Calcutta.

“During the drive my mother noticed that my father’s jacket, which he had discarded due to the heat, felt unusually heavy.

“I was to learn later that my father had carried a Webley 0.38 revolver, the purpose of which, at that time, seemed somewhat obscure.

“It could well have been to defend us against rioters or, if things got really out of hand, to ensure the Miln family a speedy exit!

“For all these events took place when civil unrest was gaining momentum towards the Partition of India in 1947.”

Death knell for Dundonians

In August, 1947, when, after 300 years in India, the British finally left, the sub-continent was partitioned into two independent nation states: Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan.

Immediately, there began one of the greatest migrations in human history, as millions of Muslims trekked to West and East Pakistan, while millions of Hindus and Sikhs headed in the opposite direction.

Many hundreds of thousands never made it.

Partition meant that 75% of the jute growing areas were in Pakistan, but all 106 mills, the baling centres and export hubs were in India.

Jute was the subject of the first inter-Dominion agreement.

However, the devaluation of the Indian rupee and Pakistani demands for a share of the export tariff led to break downs.

The Indian government issued directives that more and more locals should be employed in positions that were held by Europeans.

There was a mass exodus of expatriates out of Bengal, and by the early 1950s, most of Calcutta’s mills had passed into Indian ownership.