Napoleon’s lost legions were the cunning instigators of some great escapes from Perth prison.

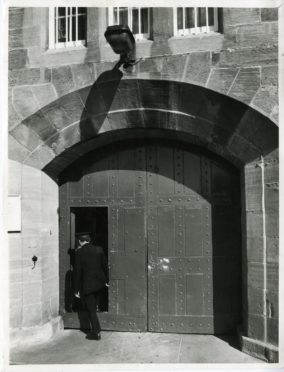

The prison’s old C Hall was part of the original Perth prison which housed the French prisoners when it was known as the Depot.

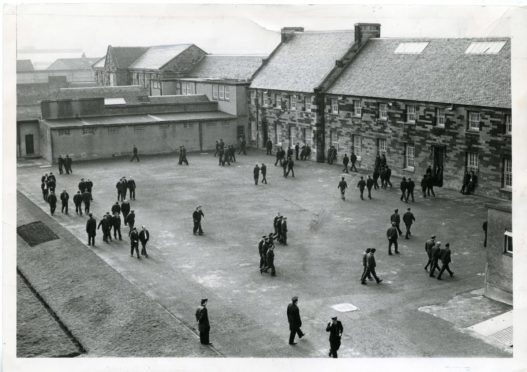

Built in 1811-12, its original purpose was to accommodate 7,000 French prisoners from the Napoleonic wars.

Workers went on strike during construction

Quarrymen and carters were advertised for on September 5 1811 and 11 months later it was complete after costing £130,000 to build.

At the peak of activity, 1,500 men worked on its construction and much of the stone used came from Kingoodie Quarry in Invergowrie.

Incidentally there was a strike for higher wages while it was being built and when it was full it held more French prisoners than anywhere else in Britain.

The Auld Alliance was reflected in the attitude of the local people to the prisoners.

When the first 400 were landed at Dundee by the transport Matilda, from Plymouth, in August 1812, kindly women gave the prisoners bread and water.

A detachment of the Renfrewshire Militia provided the escort for the trek up the Carse to Perth.

Some of the Frenchmen were accommodated overnight in a church at Inchture.

After they left in the morning the beadle discovered that two mort cloths were missing.

He pursued the party to Perth and knapsacks were searched.

The culprit was ostracised by his comrades and sentenced to 24 lashes with the ropes end.

He fainted after six or seven but the punishment was completed.

Captain E.J Moriarty, who was in charge of the Depot, allowed the prisoners to hold markets.

They bought such luxuries as they could afford and sold toys and other ingeniously constructed items they had made with odds and ends.

By December there were 4,626 prisoners in Perth and by January 21 1813 there were 6,788 which was only 12 less than the building was designed for.

There was only one successful escape from the Depot

The sailors, who included privateer captains and crews, were, by the nature of their calling, a daring and resourceful bunch.

After tunnelling or climbing out of prison, they instinctively headed for the sea in the hope of getting hold of a ship.

There is only one recorded instance of a successful getaway from the country by sea when three men got out over the wall on a foggy January morning.

They reached Broughty Ferry and succeeded in buying bread and spirits from a house in Forthill.

Newspaper reports indicated an absence of the fear and hatred generated by more recent conflicts.

Apparently the suspicions of the Forthill family were not aroused by the foreign accents of their visitors.

Down at the waterfront the trio on the run managed to steal the fishing boat Nancy and sailed away to possible freedom.

The vessel was seen under way, but, as it was known she had been prepared for cod fishing, nobody paid any attention until it was too late.

The 15-ton Nancy, herself a prize of war – she had been captured from the Danes – had been provisioned with oatmeal and salt, so the trio were in no danger of starvation.

The most ambitious escapee was a former privateer captain who toyed with the idea of stealing a ‘London boat’ from the crude and muddy Dundee Harbour.

The Fife Packet – 94 tons – was no giant, but she had aboard a full cargo of linens valued at £16,000 for the London market.

Four men, headed by the captain, boarded her silently during the night, but couldn’t get her off the mud.

In any case, her sails weren’t bent, and this could not have been done without attracting unwelcome attention.

In search of a softer target, they doubled back to Kingoodie, where they boarded a sloop used to ferry stone to Dundee.

The owner, Captain Mustard, found two of the men hiding under a sail – and it was back to Perth and captivity for the four men.

The most elusive Frenchman of the lot, a tunneller, reached Montrose, where he was put under lock and key before he could interfere with shipping.

He got away after picking three locks and headed inland but was recaptured near Alyth.

As the Depot at Perth didn’t seem tight enough to hold him it was decided to transfer him to another prison at Penicuik.

A sergeant and seven soldiers were detailed as an escort.

They deposited him overnight in the jail at Kirkcaldy.

By morning he had gone again to hard earned freedom.

Thousands turned out to wave them off to France

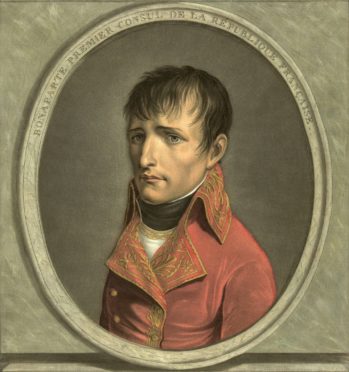

When the war was temporarily over, and Napoleon was banished to Elba, French prisoners refused to believe their hero had been defeated until they were released.

By July 1814 they had all left although some sadly died in captivity.

All of the French prisoners were repatriated after Napoleon’s defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 and thousands of Perth people turned out to wave them off.

A flotilla of ships was engaged to take them home.

In the summer of 1814 the streets of Dundee were thronged with more than 1,000 Frenchmen who had been allowed ashore from half a dozen ships which were prevented from leaving the river by bad weather.

They had been complaining because no spirits were served in the transports, and were seeking to buy food and drink from their slender resources.

Curious crowds followed the Frenchman who were described as “having certain peculiarities of visage, such as huge moustaches”.

One newspaper said they looked “healthy and agreeable”.

After his defeat and dethroning in 1814, Napoleon came to an agreement with the coalition of nations that had taken him down and left France for the isle of Elba.

Napoleon would be allowed to rule Elba, which had 12,000 inhabitants.

On February 26 1815, Napoleon managed to sneak past his guards and somehow escape from Elba, slip past interception by a British ship, and return to France.

Napoleon was subsequently exiled to the island of St Helena off the coast of Africa.

Exiled Napoleon spent final years living in misery

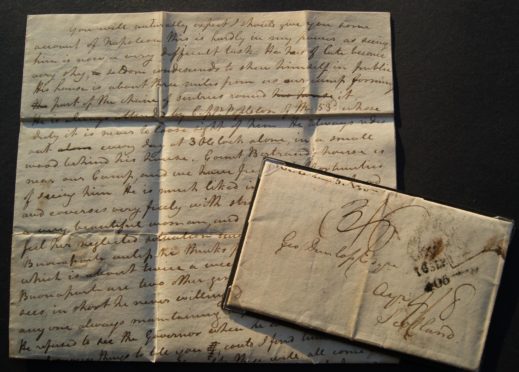

Letters which have surfaced in Scotland reveal Napoleon as a depressed recluse and “pretty much in the huff” during his captivity on St Helena.

The three letters were written in the summer of 1816, shortly after Lt George Duncan, an Army surgeon with the 66th Regiment of Foot arrived on St Helena as part of the guard for the fallen French Emperor.

They were sent to his father, also George Dunlop, a solicitor in Ayr.

Perth-based historian and author Norman Watson, who acquired the letters from an old-time collection, said Dunlop’s remarks add an important eyewitness account to what is known about Bonaparte in his early months on St Helena.

“The Dunlop correspondence comprises only a handful of surviving letters,” said Dr Watson.

“This is largely because the archives of the Dunlop & Co law firm were apparently sent for paper salvage during the Second World War.

“A few letters surfaced in London salerooms in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

“Two or three have appeared at auction since, but they are exceptionally rare.

“The three recently uncovered have, I think, by far the best descriptions of Napoleon.

“They are also the earliest-known letters from Lt Dunlop on St Helena.”

When Napoleon surrendered, he expected his captors to be honourable enough to provide him with a country estate in England or to exile him to a pleasant retirement in the United States.

“Although Napoleon was given everything he could wish for – except his liberty – Lt Dunlop found him ‘gloomy’ and uncommunicative,” said Dr Watson.

Napoleon maintained a gloomy reserve on the island

The first letter, written from St Helena on June 3 1816 reveals that the unhappy French Emperor had refused to meet the island’s governor.

“You will naturally expect that I should give you some account of Napoleon,” said Lt Dunlop.

“He has of late become very shy, seldom condescends to show himself in public.

“His house is about three miles from us; our camp forms part of the chain of sentries around it.

“He is always attended by Capt Poppleton of the 53rd, whose duty it is never to lose sight of him.

“He always rides out every day at 3 o’clock alone in a small wood behind his house…In short, he never willingly sees or converses with anyone, maintaining a gloomy reserve.

“He refused to see the Governor when he arrived.”

“Eventually, Lt Dunlop was presented to Napoleon,” said Dr Watson, “and this appeared to raise his opinion of the prisoner.”

In a letter to his uncle in Bristol on July 5, Lt Dunlop reported that Napoleon had addressed several questions to him and had appeared in excellent spirits.

He concluded that he had “of late mixed much more with Society than he formerly did, and as I am stationed within half a mile of his residence, I am likely to see more of him”.

But the third letter, to his father just two days later, told a different story: “You will no doubt expect some account of Bonaparte.

“I have only seen him once and I confess I was much disappointed.

“He has very little in his appearance remarkable, and in dress is far from being good.

“He very seldom goes out and when he does he is always attended by an officer of the 53rd.

“I frequently see the other [French] generals who are to appearance more like their rank than he is.”

Dr Watson said Lt Dunlop wasn’t much taken with the man who had conquered half of Europe.

The island, though, fascinated him.

The letters describe in detail the hardships for the British garrison.

There was little fresh meat and only a few vegetables.

No spirts were permitted and only wine ‘of a very bad quality’ was allowed to the troops at the rate of a pint daily, “and with a pound of salt beef and very good bread, forms their rations”.

On a positive note, he was pleased to find his pay ‘almost double’ that for service in England – over £312 per annum.

Napoleon was a man who took his vendettas to the grave.

He died at St Helena on May 5 1821, at age 51, most likely from stomach cancer.

What happened to the Depot?

In 1842, the Depot began service as a civilian prison.

The prison gained further notoriety around 1914 as the only prison with the facilities to force feed hunger striking suffragettes, which caused a national outcry, with Perth being besieged by suffragette protesters, parades, processions, night-time vigils at the prison gates, and the Dundee contingent renting a flat opposite so that they could shout encouragement to their imprisoned sisters.

And now streets close to the prison are named after two of the four women.

In September 1930 a memorial plaque was unveiled to mark the burial ground of French prisoners of war who died in Perth between 1811 and 1814.

Unveiled by William Anderson the Secretary of State for Scotland the plaque read: “Near this spot was interned a number of French prisoners of war who died in military capacity at Perth about the year 1812.”

It is currently Scotland’s oldest prison.