Archie Macpherson has never forgotten the visceral violence which erupted on the Hampden pitch at the end of the 1980 Scottish Cup final between Rangers and Celtic.

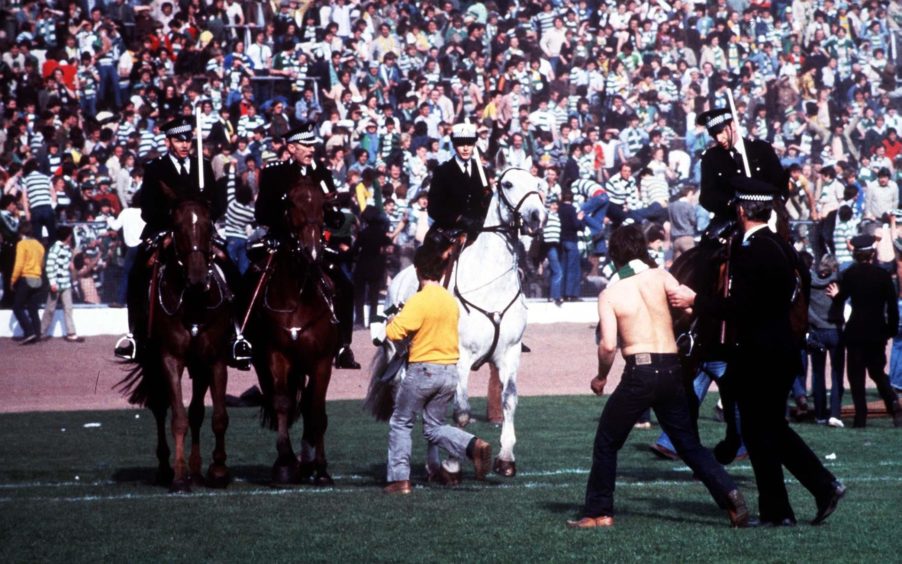

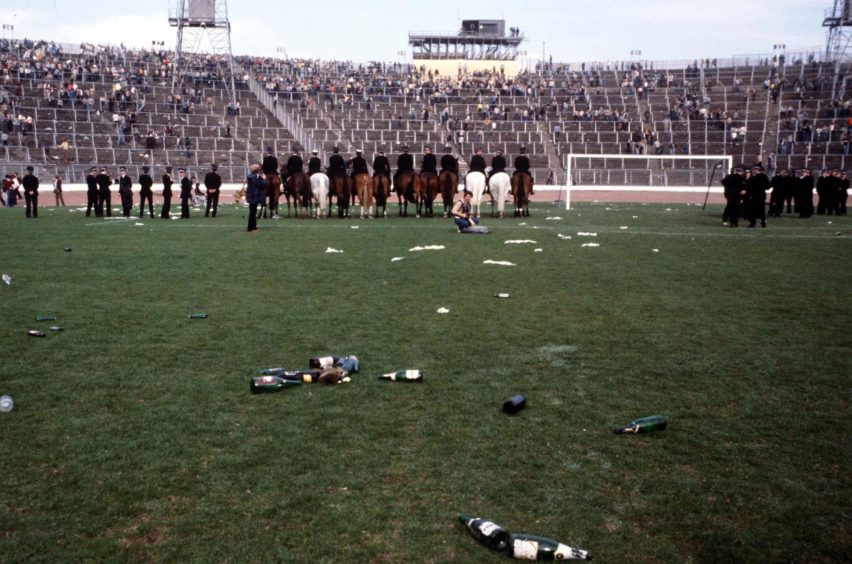

The pictures, which were beamed all over the world, sparked instant condemnation as supporters on both sides of the Old Firm divide, attacked one another while an inadequate number of police officers, some on horseback, attempted to stem the tide.

The TV images captured the squalid moments when hundreds of fans, fuelled on a grisly mixture of excessive alcohol consumption and sectarian loathing, battered lumps out of one another after the SFA’s security perimeter was breached.

Bricks, bottles and cans were thrown by the perpetrators, who also used iron bars and wooden staves from terracing frames as weapons.

And, amid the sustained carnage, Macpherson described what he was watching in the language of a war correspondent.

He told his audience: “This is like a scene out of Apocalypse Now…we’ve got the equivalent of Passchendaele and that says nothing for Scottish football.

“At the end of the day, let’s not kid ourselves. These supporters hate each other.”

It was shocking and it needed a swift response. And, within less than a year, an act of Parliament was passed which banned the sale of alcohol within Scottish sports grounds.

It came into force 40 years ago today.

And, despite pleas from some in football in the intervening period, it remains the law.

The game itself was a non-event

The ferocity of the mayhem at Hampden Park completely overshadowed the preceding 120 minutes of largely pallid action.

As Macpherson said this week: “It was a very ordinary match, with hardly any football, very tense, full of mistakes….one of those big games where both sides seemed more afraid of losing than actually going out and winning.

“Eventually, after it moved into extra time, Celtic scored the only goal [through George McCluskey], but it was what happened after the whistle had gone that made all the headlines for the wrong reasons.

“It has stayed with me ever since. But I wasn’t surprised at what took place. The elements were all in place for a perfect storm – it was a lovely afternoon, there was lots of booze, fewer police than there should have been, tactical mistakes by the force [Strathclyde Police] and it unleashed the savagery and hatred which existed out there.”

The ban worked in stemming violence

The veteran commentator added: “It was obvious that something had to be done to tackle the problem of drunken hooliganism and I thought the right measures were taken. The ban was totally justified. And it worked.

“I remember talking to Ernie Walker [the former SFA secretary] and he described it as the most effective piece of legislation ever passed in Scotland. It made such a difference.

“Within a few months, Ernie told me that after the 1981 Scottish Cup final between Rangers and Dundee United [which finished 0-0, prior to the Ibrox club, inspired by Davie Cooper, winning a replay 4-1 three days later], there was nothing more than a few crushed Coca-Cola cans left on the terraces.

“And no trouble either. It definitely made a difference when the ban was introduced. And nobody could possibly have wanted a repeat of what happened in 1980.”

Arguments raged over the guilty parties for Cup shame

Both halves of the Old Firm were found to be culpable in the shameful events which led to more than 200 arrests being made in the Hampden area of Glasgow.

A blame game ensued, even as the clubs were fined £200,000 apiece. Celtic were critical of the police for their handling of the riot, and argued the SFA had not taken sufficient measures to prevent a fan invasion at the climax.

The authorities, including the governing body, had assumed the perimeter fences would prevent supporters from encroaching on to the playing area, but these were subsequently found to be no deterrent to those who were determined to get on the pitch in response to what they viewed as provocative behaviour from the winning team.

In the aftermath, the police blamed Celtic fans for causing most of the disorder, and the war of words eventually forced political intervention at the highest level.

George Younger, the Secretary of State for Scotland, concluded that alcohol had been the main reason for what he described as “disgraceful civil disorder” and argued that Celtic players in particular had to accept more responsibility for their actions.

This led to the implementation of the ban on February 1 1981, which prohibited the sale of alcoholic beverages within Scottish sports grounds, while spectators were also forbidden from bringing alcohol into stadiums.

It was move which preceded a turbulent decade for sport, which was marked by a series of dreadful tragedies at football stadiums across Europe, including the Bradford fire which killed 56 people in 1984, the Heysel disaster, which claimed 39 lives at the European Cup final between Liverpool and Juventus in Belgium the following year, and the death of 96 Liverpool fans at Hillsborough in 1989.

Nor were the police in any way half-hearted about making the law stick – as I found out when I was in Paisley to cover a match at the start of my sportswriting career.

‘Put it in the bucket, son, or you’re nicked’

It should have been a routine assignment: the task of covering St Mirren v Hamilton for a Sunday newspaper early in 1989.

But I made the mistake of carrying a bottle of Diet Coke in my bag as I approached the entrance at Love Street.

A police officer moved towards me and asked to inspect the contents of my hold-all.

I wasn’t worried. Or not at first. This was standard practice. I opened it for him and he pointed to the bottle. “What’s that you’re carrying?”

I thought he was joking and showed him my press card. “It’s just a bottle of juice. Don’t worry, I’m just taking it to the press box.”

His response was incredible. “Do you think this is funny? You’re not allowed to bring sealed containers into football grounds. And how do I know you’ve not put whisky or vodka into it? Get rid of it. You’re not coming in here until you do.

I replied, still politely: “Isn’t this a bit over the top? It’s just a soft drink.”

Then he said, with more than a hint of menace: “Are you listening to me? Put the bottle in the bucket, son, and shut up – or you’re nicked.”

It wasn’t just football fans who had a tough time from the law in the 1980s.

There were some complaints from football officials about the stringent nature of the alcohol ban and these intensified when Kenny MacAskill, the Cabinet Secretary for Justice in the first SNP Government, partially eased the restrictions in 2007, allowing the sale of alcohol at international rugby matches at Murrayfield.

In 2018, the SFA, Police Scotland and Scottish Government officials met to explore the idea of using the Euro 2020 matches scheduled for Hampden – the tournament later fell victim to the Covid-19 pandemic – as a pilot to investigate the possibility of easing or even ditching the ban.

The football authorities pointed out that, under the regulations, Glasgow would be the only one of 12 host cities across Europe where supporters would not be able to buy alcohol inside the stadium.

But the Scottish Police Federation, which represents rank-and-file officers, remains strongly opposed to the idea.

David Hamilton, the SPF’s vice chairman, said: “We don’t have the same problems in rugby stadia that we do in football.

“We don’t see toilets being trashed, we don’t see pyrotechnics. They are particular problems for football and the idea of adding alcohol to that mix does not seem to make sense.”

Aberdeen supporters call for review of the law

The subject might be academic at the moment while football matches are being played behind closed doors with no fans at grounds because of the pandemic.

But Aberdeen aficionados are among those believe that the prohibition on alcohol sales should be addressed once a semblance of normality has returned to sport.

The Dons Supporters Trust told the Press and Journal: “We think it needs to be reviewed when we are allowed back into stadiums.

“It is unfair on the majority of clubs as the ban stemmed from the Celtic v Rangers Scottish Cup Final.

“We don’t think rugby fans being allowed to drink alcohol is significant, but football just needs to get its own house in order.”

Mr MacAskill, who is now a Westminster MP, said: “I have supported change before, but it will be a different world post Covid.

“Money will be tight for clubs and the income would be welcome. Drinking patterns, though, may have altered with pubs closed and home drinking becoming the norm.

“It seems to me that it is a far wider consideration that will be needed.”

What does Archie think about the issue?

Archie Macpherson has watched more football matches than most people and observed shifting patterns in fan behaviour down the decades.

And he believes that, while the ban on alcohol made sense in the 1980s, society has changed in many ways and football is now more inclusive and family-friendly.

In which light, he isn’t averse to the return of alcohol sales in a controlled environment at grounds when the authorities decide to examine the matter again.

He said: “Football is easier to police now than it used to be, with supporters in all-seated areas rather than on the terraces.

“And I think fans have become better at self-policing and keeping their discipline. They know that if there is any trouble at games, it will be their club which suffers.

“I don’t see anything wrong in experimenting to see how it works. Hopefully, now that we have reached the Euro finals, Scotland won’t be the only country where good-natured fans can’t enjoy a pint while they’re watching the games.

“Or at least if there are any supporters in the stadiums this summer.”

More Than a Game by Archie Macpherson is published by Luath.