A Dundee woman sent to an orphanage at the heart of a child abuse scandal after her father was killed in the Spanish Civil War is on a mission to find out more about her family’s past.

Jane McHugh became an orphan at three years old when her father was killed in battle during the Spanish Civil War.

Her mother had died when she was a baby, so she was sent to the notorious Smyllum Park Orphanage in Lanark – 90 miles from her home in Dundee’s Lochee.

During her decade of incarceration, Jane witnessed untold cruelty including beatings and ill-treatment.

Deprived of food, she survived by stealing bags of sugar.

It was a hellish, traumatic upbringing that scarred Jane to the point where she couldn’t bear to speak about her experiences until she was 78 years old.

Now 87, Jane is seeking more information about her early childhood, pre-Smyllum, and is desperate to find a photograph of her father James McHugh, described as a “forgotten war hero”.

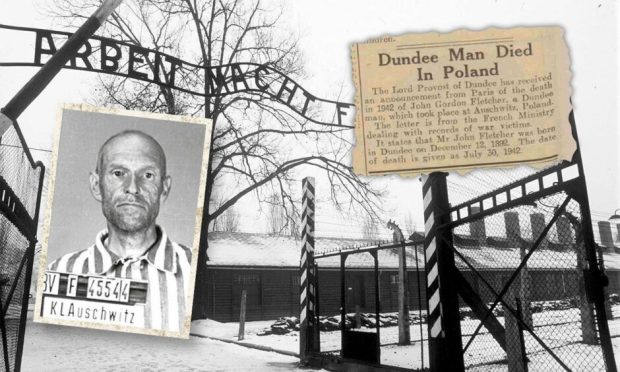

Dundee-born merchant seaman James was killed at the Battle of Gandesa in April 1938.

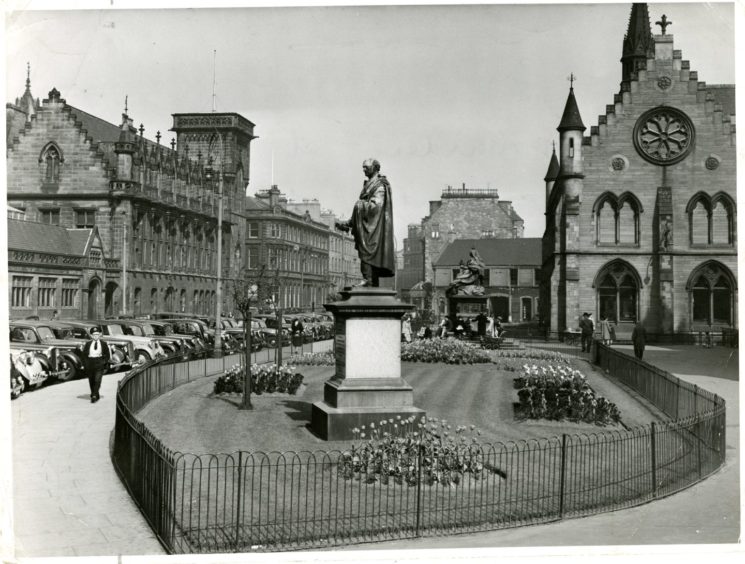

An error on a memorial plaque erected in Dundee’s Albert Square in February 1975 wrongly listed James’s brother John as a result of a mix-up with documents.

Decades later, when James’s family expressed their distress at the lack of recognition, a second “supplementary” plaque was erected beside it – in 2008.

Smyllum experience

After James died, Jane – known to her friends and family as Jean – was cared for by her grandmother until she was seven years old.

At that point, social services decided she should go into Smyllum Park Orphanage.

“Her Uncle Pat and Georgina wanted to look after her, but because they had three or four children, they couldn’t offer her a room of her own, which the social services were not happy with,” explains Jane’s daughter (James’s granddaughter) Karen.

Smyllum Park Orphanage was opened in 1864 at Smyllum Park in Lanark.

The institution was run by a Catholic order of nuns and housed 11,600 children aged between one and 14 years old, including those who were blind or deaf-mute, before it closed in 1981.

Jane couldn’t bear to speak about her traumatic experiences at Smyllum until nine years ago.

“Her memories are very vivid and she talks about her experience there, often, these days,” says Karen, an art therapist who lives in the East Neuk.

“When mum arrived at the orphanage, she was read a letter by one of the nuns.

“It said that she was ‘never to be adopted’, which had a profound effect on her and she didn’t understand why this would be the case.

“I’ve often said it was perhaps because the family were trying to get her back with them.”

The orphanage was at the centre of an inquiry into historical allegations of child abuse in 2017.

The Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry found that many children at the orphanage were sexually abused and beaten with leather straps, the “Lochgelly Tawse”, hairbrushes, sticks, footwear, rosary beads, wooden crucifixes and a dog’s lead.

Lady Smith, who chaired the inquiry, concluded it was a place of fear, threat, and excessive discipline.

Some children were sexually abused in Smyllum by priests, a trainee priest, nuns, members of staff and a volunteer. The abuse was, in some cases, prolonged.

Children who were bed-wetters were beaten, put in cold baths and humiliated in ways that included “wearing” their wet sheets and being subjected to hurtful name-calling by Sisters and other children.

Many children at the orphanage were sexually abused and beaten with leather straps, the ‘Lochgelly Tawse’, hairbrushes, sticks, footwear, rosary beads, wooden crucifixes and a dog’s lead.”

Many children were force-fed and made to queue in a state of undress for a bath and shared bathwater that was too hot or cold and dirty.

Children were abused for being left-handed and forced to use their right hands instead.

Some were abused for being Protestants and one child was told the Jewishness would be knocked out of him.

Lady Smith’s report also highlighted the case of Samuel Carr, a child in Smyllum who died aged six as a result of contracting a severe and vicious E. coli infection after contact with a rat.

He was malnourished and had received a severe beating from a Sister not long before his death.

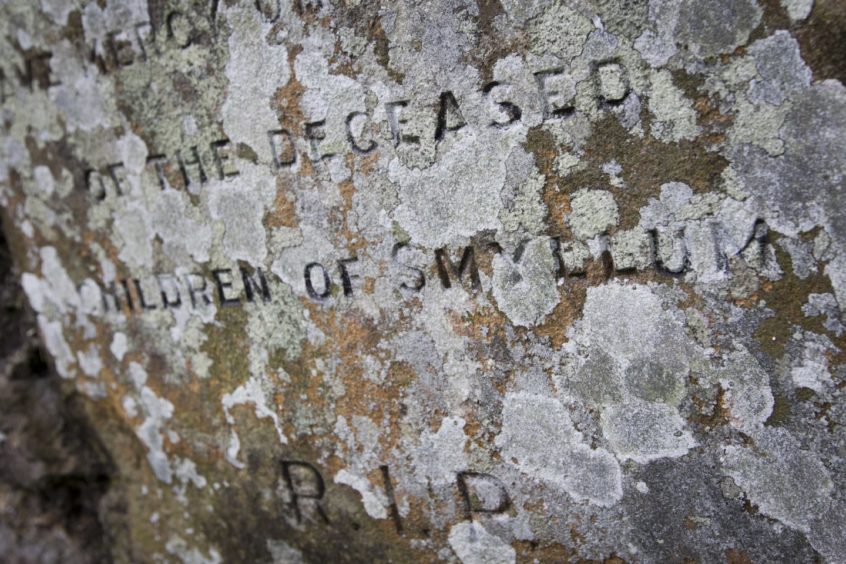

In 2003, hundreds of children’s bodies from the orphanage were discovered in a mass, unmarked grave at nearby St Mary’s Cemetery in Lanark, just a three minute drive from the orphanage.

An investigation revealed at least 400 children were buried in the plot.

A third of those who died were aged five or under. Just 24 in total were aged over 15, and most of the deaths occurred between 1870 and 1930.

While Jane is reluctant to go into details, Karen says her mum spent years suffering from dreadful nightmares about Smyllum and that reading about the case made her “hugely upset” and ill.

“She had nightmares about the children that were beaten at night and felt guilty she hadn’t managed to ‘save them’,” she says.

“She would find out that they had died, some just not appearing in the morning.

“Mum went to reunion meetings a few years back for Smyllum survivors, supported by my sister Elaine, in the hope she might meet someone she had known there, although she never did.

“She survived at the orphanage by stealing handfuls of sugar, as they were deprived of food.

“Sometimes a kind younger nun put some chocolate under her door.

“But otherwise, it was a dreadful and cruel environment. Mum only ever wanted an apology from them.”

Aged 17, after years of scrubbing floors and stairs in the orphanage, Jane enrolled to become a nurse at Dundee Royal Infirmary.

She married Douglas William Johnston in Dundee in 1959, becoming Jane/Jean Johnston.

The couple were married for 60 years until Douglas, described as a “staunch Dundonian man”, died on February 3 2019 – two years ago today.

Jane was a nurse and nursing sister at Adamson Hospital in Cupar for 27 years, where she could be seen cycling to work every day.

“She is a sweet natured, kind, witty and fun woman and dad always said he married the ‘best looking woman to come out of Dundee.” says Karen.

Jane took Karen along to see the memorial plaque in 1975 and mother and daughter experienced “great disappointment” at not seeing James’s name on it.

War hero

Jane has only one photo of her mother Rosie and one of herself as a child but has never seen a photo of her father.

“As a family, we have searched in vain for years, without success,” said Karen.

“It would be amazing if someone could help locate a picture of my grandfather James McHugh for my dear mum.

“My sisters Lesley and Elaine have been very proactive in looking too, but to no avail.

“Mum wishes that she had known her father more and for longer. And to think he was a war hero!

It would be amazing if someone could help locate a picture of my grandfather James McHugh for my dear mum.”

“She remembers him carrying her around on his shoulders around Dundee and up the Law. She said he seemed ‘a mystic figure coming and going’.

“Mum has said often in the past that it upsets her that her father went off to fight knowing that she would be orphaned if anything happened to him.

“And of course, he was killed in battle when she was only three years old.”

Family affairs

Jane was told that James and John fell out – “because John committed driving offences and gave his brother’s name to the police”.

“It was apparently in the paper, with James being made the scapegoat,” says Karen.

The bronze memorial plaque for 16 volunteers, all members of the British Battalion, who died during the Spanish Civil War was unveiled on February 23 1975 in a small garden to the east of McManus Galleries in Dundee’s Albert Square.

The ceremony was led by Dundee International Brigade veteran Arthur Nicoll.

This wrongly listed James’s brother John – and not James.

“After many years of campaigning – the council said it was too expensive to amend the original plaque – they added a supplementary, second plaque in October 2008,” says Karen.

“I know this upset my mum hugely, as his death affected her life so dramatically.”

Research

Karen discovered her grandfather James died at the age of 26 in April 1938 in Gandesa, in the province of Tarragona, Catalonia.

James was a seaman in the Dundee branch of the National Union of Seamen and an organiser for the National Unemployed Workers Movement in Dundee.

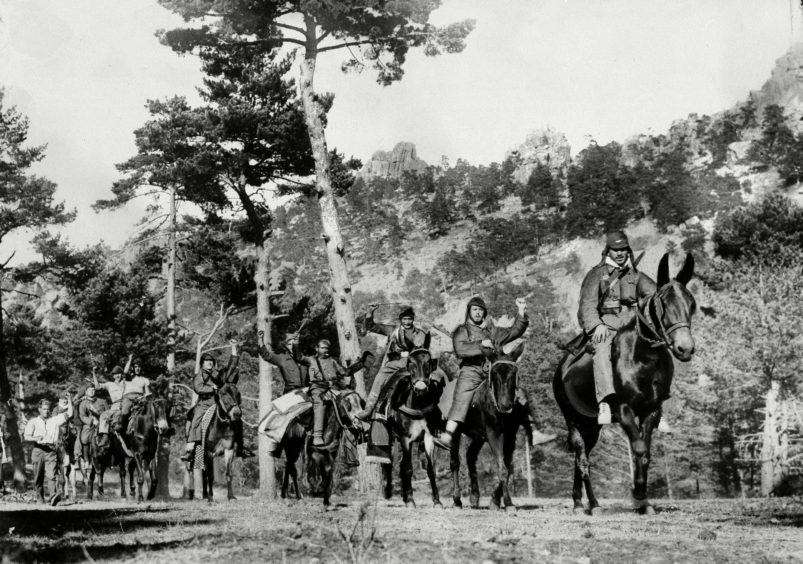

He arrived in Spain on December 10 1937, fought at Hijar and Calaceite and was reported as “missing in the Aragon retreats” and was likely killed at the Battle of Gandesa between April 2 and 4 1938.

In the middle of January 1938, the British Battalion was fighting in deep snow in a vain effort to hold the city of Teruel, which was said to have been “spectacularly taken” on January 8.

In the retreat of 70 miles that followed, from Aragon to the coast, they were twice almost surrounded but got away.

But on March 31, in the municipality of Calaceite, they were ambushed by Italian tanks and Moorish cavalry, having mistaken them for their own forces.

They lost a hundred men who were captured and perhaps a dozen were killed.

Only 80 volunteers were left in the Battalion and they made their way to Gandesa, arriving on April 2.

Here they attempted to delay the insurgents before retreating back over the River Ebro at Cherta. With the bridges across the river blown, the Nationalist advance was at last stemmed.

- Do you have any information about James McHugh – or a photograph of him? Get in touch at: gritchie@dctmedia.co.uk