Derelict and decaying Strathmartine Hospital is a target for vandals, arsonists and graffiti artists. With plans to develop and partly-demolish the sprawling site – which has been described as a “potential deathtrap” – Gayle Ritchie goes behind the crumbling walls of the hospital to expose its dark and hidden history.

The tattered shreds of 1960s-style floral curtains shift soundlessly against gaping windows, the jagged panes of smashed glass glinting in the dim winter light.

Mould spores cling to rotting walls and planks of desiccated chipboard hang from doorways in a lacklustre attempt to keep out intruders.

Gazing down dark, desolate corridors, Stanley Kubrick’s iconic horror film The Shining springs to mind, although the grim spectre of decaying Strathmartine Hospital is more likely to give you nightmares.

At the bottom of a dank stairwell, you’re confronted with a skull and crossbones crudely spray-painted on a wall with the challenge: “If you can find the body, you win”, tagged beside it.

A few feet away, a ward boasts a wallpaper that seems incongruously cheery.

An off-white shade, it features clocks, flowers and items of crockery.

On walls nearby, the paper is torn and shredded, the paint peeling, the brickwork behind it exposed to the elements.

Crumpled on the ground alongside chunks of fallen rubble are long-forgotten festive decorations – some tinsel and an ironic “Merry Christmas” sign.

At every turn, there’s the drip, drip, drip of water seeping its way into the rotten core of the structure.

And yet, amidst all the decay and neglect, there’s new life.

Nature has reclaimed many of Strathmartine’s abandoned buildings, now home to sprawling swathes of vegetation.

Trees branch up through floors, and ferns sprout up through the rubble.

Moss, a fan of the damp, thrives here, too.

Some might find beauty in the abandonment, but the overriding sense at Strathmartine is of foreboding, of sadness, of neglect.

As it sinks further into decline, very few of its building, spread across 44 acres, can be saved.

The only hope is that a new lease of life can be injected into the site via plans for a major redevelopment in spring.

Asylum and orphanage

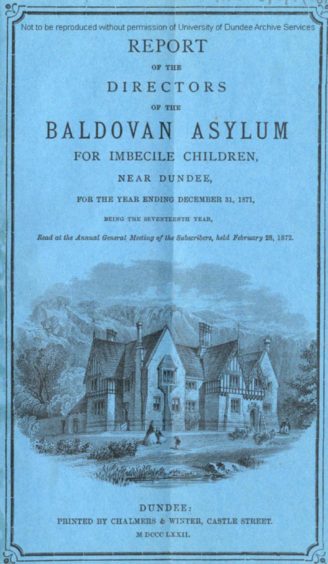

Strathmartine Hospital started life in the 1850s as the Baldovan Institution, an orphanage and asylum “for imbecile and idiot children”.

Founded in 1852 by Sir John and Lady Jane Ogilvy, it was the first facility of its kind in Scotland.

Today the word “asylum” has all sorts of negative connotations, but for many people, Baldovan was a sanctuary – a place to call home, somewhere safe. A sanctuary.

There was a dark side to its history too, with allegations of abuse, cruel forms of punishment and suicide in the mix.

The hospital was transferred to the NHS in 1948 before it was decommissioned in stages in the 1980s.

It finally closed in 2003, becoming a target for vandals and fire-raisers.

Plans have been approved by Angus Council to transform the site into a new housing development, a monumental task which involves restoring some buildings but demolishing the vast majority.

Memories, both positive and negative, remain in the hearts and minds of those who lived and worked at Strathmartine and many people care about its future.

Potential death trap

Local campaigner Karen McAulay has fought to save the structure from falling into disrepair for decades.

“It’s full of dangerous buildings – Strathmartine Hospital has become a potential death trap,” she says.

“Over the years I’ve watched it degrade and deteriorate and be targeted by vandals and arsonists to the point where there’s only a slim chance of some buildings being saved.”

Karen’s mum, grandmother and great-grandmother all worked at Strathmartine.

She’s explored the crumbling buildings often, becoming increasingly despondent each time she picks her way through gaps in fences, or walks through doorways which have been wrenched open by vandals.

Aware many of the buildings are structurally unsafe, she’s keen to see security increased to ensure anyone accessing it doesn’t have an accident or loses their life.

Karen is campaigning to have the former chapel of rest – a listed building that is currently earmarked for demolition – transformed into a heritage centre.

“We’re left with four listed buildings and two cottages that should be developed into properties but the rest of the site will unfortunately be demolished,” she says.

“It would be reasonably low cost and quick to convert the chapel of rest into a heritage centre which would be fantastic. It would tell people about Strathmartine’s story and make sure we stay connected to its past.”

Institutional punishments

Karen has delved deep into the hospital’s history and has many shocking and heart-wrenching stories.

“Some wards in the 1950s had ‘time-out’ rooms and Strathmartine in fact had a very strict time-out policy.

“These rooms were very small – no bigger than a large cupboard – and most had steel shutters and no windows. People were kept in a room with no windows, steel shutters and no light.”

Some residents were also placed in what they referred to as “tea boxes”.

“These were small wooden boxes that tea was delivered in,” explains Karen.

“I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say these boxes were smaller than coffins.

“Residents were placed in them until they calmed down. The impact of such institutionalised behaviour had a dramatic effect and many struggled with trauma for years.”

Former patient Jimmy Laing spent 50 years in various institutions and was at Strathmartine, then Baldovan, in the 1950s.

His book, 50 years in the System, recounts the brutality he suffered there.

He recalls being restrained after running away and being given “the treatment” by a doctor.

“The treatment was to hold your head underwater until you almost stopped breathing, allow you up for air and then push you back down,” says Karen.

“Technically, it was waterboarding, a form of torture.”

Many people who had learning disabilities and struggled to articulate what was wrong in their lives “ended up” at Strathmartine, says Karen.

“It seemed to be the place to go. The authorities would be like, we’ll get you up there for a short while but they’d still be there years later. They’d be lost in the system.”

Former nurse

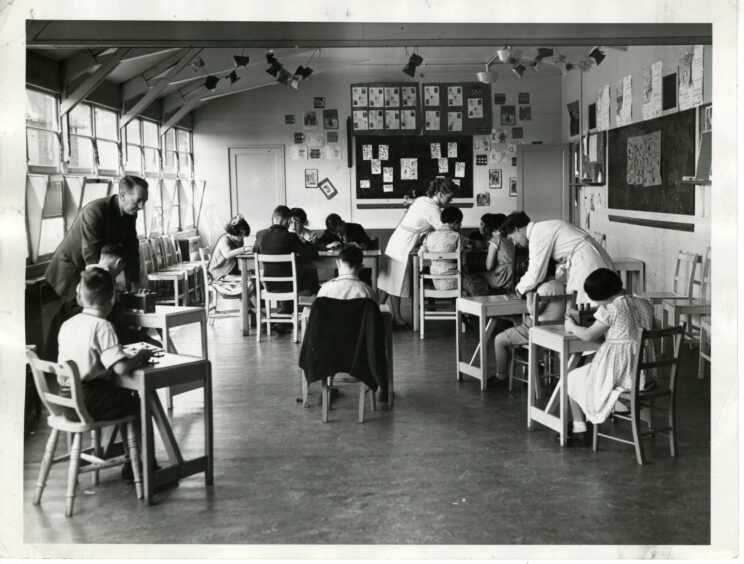

Heather Kennedy worked at Strathmartine for 34 years, starting at the age of 16 in 1976 as a governess, helping children with subjects like writing and music, and ending her career as a staff nurse.

“It breaks my heart to see it in this terrible, neglected state,” she laments, glancing in the direction of the vandalised, boarded-up wards.

“I remember how these were living, breathing wards with patients; I can see them in my mind’s eye.

“I’d be walking around speaking to them, assisting to their needs, and now these wards are absolutely trashed. It’s so sad.”

When Heather first started at Strathmartine, there were around 600 patients including babies, children and elderly people. Some wards had up to 50 people in them at a time.

“It was a lot and we were short staffed but we just got on with it,” she says.

Working at Strathmartine runs in Heather’s family with her father, several cousins, her brother and two sons employed there over the decades.

Haunted

Heather claims to have witnessed paranormal activity on numerous occasions while on duty.

“One of the main things that attracts people up here is that it’s haunted,” she says.

“I’ve had a few strange experiences which sent a chill down my spine.

“In ward 15, I was washing patients’ hands and faces with a charge nurse when she screamed.

“She said, ‘Heather, I’ve just walked through a figure sitting cross-legged on the floor and it lifted its head to look at me’. She was shaking.

“In ward five, a charge nurse was sitting with a student nurse when the figure of an older lady walked through the wall.

“That ward had a little room upstairs and I always had this terrible feeling something was pressing down or looking at me.

“On ward 11, when I was with a nursing assistant, we heard keys jangling and assumed it was a manager. We looked all round the ward but no-one was there.”

The staircase in the main hospital building was also a source of worry for Heather.

It was the site of a suicide in the 1950s.

“Before I knew about that, I used to hate walking up the stairs and going round the bend,” she recalls. “I later found out a doctor hanged himself there in the 50s.

“A lot of people died at Strathmartine so there’s bound to be some sort of feeling around that.”

Heather is keen to see the listed buildings developed but she is keen to see the rest razed to the ground.

“It’s a deathtrap,” she stresses. “People are constantly setting fire to it. Relatives of patients who lived here just want to let it be.”

A happy place

Not everything that went on was bad; there were a lot of positive things about Strathmartine, too.

“People fundraised for extras for residents in the 1970s and that paid for a swimming pool, a playpark and a minibus so they could go on day trips and holidays,” says Karen.

“Staff cared and went the extra mile; they knew residents deserved better.”

Heather agrees. She breaks into a broad smile when she recalls the fun times she had with residents.

“Christmas Day was amazing! We had festive songs playing, Santa came round the wards, presents were opened and we had a lovely dinner. The staff loved it as much as the residents.

“They had dances and a sweet shop and got to go on bus runs to the cinema and shops.

Twice a year patients enjoyed a mini-break to Arbroath. They would explore the Angus countryside and enjoy an ice cream or fish and chips.

“People have such negative things to say about how terribly people were treated,” says Heather.

“But for many people, this was their home, their sanctuary, their safe place.”

Archives hold institutions to account

Dundee University archivist Caroline Brown has researched the history of Strathmartine Hospital and worked on a series of films which detail the experiences of former staff and residents.

“It started off in the 1850s partly as an orphanage and partly as a school for children with what we’d now call learning disabilities,” she explains.

Back then, many of the patients who lived at the institute, initially called the Baldovan Hospital and then Baldovan Asylum, were referred to as “feeble-minded”, “mentally-defective”, “lunatics” and “idiots”.

Leaflets from the 1850s reference the asylum as being established for the “cure of imbecile and idiot children, and as an asylum for “imbecile children”.

“In the 19th Century, hospitals for people with learning disabilities or any kind of mental illness were called asylums,” explains Caroline.

“The idea was to take people away from the cause of their illness or difficulty, maybe poor or cramped living conditions, and put them in a nice, safe area, away from the town and surrounded by beautiful countryside.

“The idea was to give them a safe place where they could be taught and properly looked after – fed, clothed, bathed, given a good routine with physical exercise.

“It wasn’t necessarily seen as a bad thing – that they were locking people away. They were generally trying to help and provide care for people.”

Some patients were encouraged to develop skills they could apply in “real” life, with boys working on the asylum farm and girls helping out nurses by making up beds and working in the sewing room, kitchen and laundry.

“Many of the stories we discovered were about how difficult it was to live and work here,” says Caroline.

“In later parts of the 20th Century, there was a lot of overcrowding. There wasn’t enough money to keep this amazing set of buildings in good repair.

“There were issues with what was called institutional care. But many things were good about it and people remember Strathmartine as a community where they forged connections.”

Caroline says archives can help hold institutions like Strathmartine “to account” but can also preserve people’s memories, good and bad.

“It’s sad when you come here and just see echoes of the past. But archives aren’t just dusty old volumes in the basement.

“They hold stories of people who lived here so they won’t be forgotten and so they can be remembered as individuals, not just people locked away in an asylum.”

Hopes for the future

Angus councillor Craig Fotheringham is concerned about the ongoing issues of fireraising and vandalism issues and is keen for work to progress on developing Strathmartine.

“The quicker something is done the better because it is a dangerous building,” he says.

“Plans have been passed by Angus Council for 244 housing units plus the restoration of the existing listed building.

“I was slightly concerned about the number of units as I felt it was urbanisation of a small village.

“However the developers said to offset the costs of the upgrade of the listed building, they’d have to make some profit off the 244 units.

“The developers will tidy up the site and bring some new community spirit to Strathmartine. Let’s hope they start in the spring.”