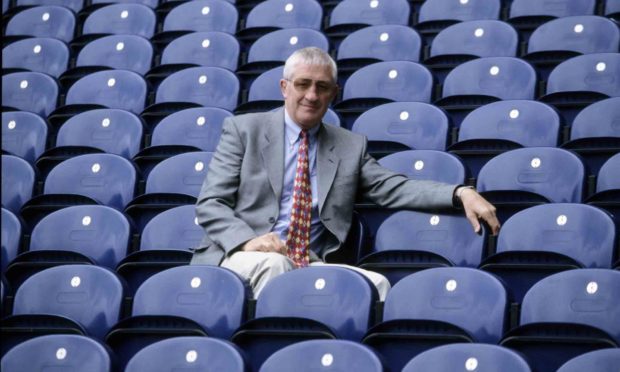

It was early in the 1990s, with Scottish rugby riding on the crest of a wave, and I was sitting in the reception area at Murrayfield Stadium, waiting for a chat with the inimitable Jim Telfer.

Suddenly, as the clock ticked towards the appointed hour, a well-known internationalist caught sight of me and asked about my latest interview subject.

When I told him, he winced, turned a puce colour, and declared, prior to making a sharp exit: “Well, I hope you’ve got a sturdy book to shove down your trousers.”

It might be unfair to describe that as a common reaction from those who played under the gnarled Borderer with a Malcolm Tucker-style penchant for profanity in the changing room, but Telfer always knew he had to push his compatriots to the nth degree when it came to tackling the likes of the English and Welsh in battle.

During our ensuing meeting, he launched into a spirited critique of the guerrilla tactics of Marshal Tito and how Scotland had far inferior numbers and playing base to the leading countries in rugby – so they had to smarter and think outside the box.

One measure of his success was the fact he celebrated his 44th and 50th birthdays on the same day – March 17 – that Scotland won their only Grand Slams of the modern era in 1984 and 1990. There he was at the helm of a transcendent period in the game.

And I’ve always been fascinated by his attitude to tackling problems and becoming one of the world’s most-respected figures in the process.

‘I developed a huge fear of failure in life and sport’

It’s not too difficult to imagine that if Telfer had grown up in Glasgow rather than the Borders, he might have developed into an Alex Ferguson-like football coach.

There was the same refusal to accept second best or tolerate slackers, a similar relentless streak of perfectionism and an ability to work best with youngsters, allied to an ingrained philosophy that Scots should stand tall in sport and in life.

As he said: “My upbringing was one where there were no privileges: you had to work for everything you got. I wasn’t born into a family with money, so I had to earn everything.

“I would always do my best to encourage the trier; the boy who, maybe, wasn’t the most talented, but showed lots of commitment and worked as hard as he possibly could,

“I came from a non-rugby family, and I had to start from scratch, so I have never had any time for people who think they are better than they really are. The players who always had excuses for not training could disappear as far as I was concerned.

“When I was making my way, I developed a huge fear of failure that was always with me. It drove me on as a player [Telfer won 25 Scotland caps and represented the British and Irish Lions eight times] and it definitely drove me on as a coach. Being raised in an environment where the landlord and the duke were the kingpins made me feel small, despite me railing against the system. It also made me a bit of a rebel.”

Passion for New Zealand has never left Telfer

I was sitting with Telfer in the Holiday Inn Crowne Plaza hotel in Johannesburg the day before the Scots met the All Blacks in the quarter-finals of the 1995 Rugby World Cup.

The match itself turned into a familiar story as New Zealand triumphed 48-30, but the beetle-browed coach has always been in thrall to the Kiwi rugby culture, which he has examined and investigated with the precious nature of a Poirot or Holmes.

These days, Scotland tends to take victories in team sport wherever it can. Even qualifying for a major tournament is treated as if it is a massive achievement. Not for Telfer it wasn’t and he was scathing about the subject during our time in the Cape.

He told me: “You don’t get into the New Zealand team because of who you are, or where you went to school, or because you have been given an easy passage up the ladder.

“You get to wear the All Black jersey because you have earned the right to wear it and their whole rugby structure, from primary school right up to the provinces, is based on giving every single youngster in their country an equal opportunity.

“In Scotland, we don’t really seem to like team sports that much. We produce individuals who are good at golf and athletics, boxing and cycling and swimming [and Telfer later praised Andy Murray’s exploits in tennis]. But getting our clubs to pull together in the same direction to create successful teams is another matter.”

Winding up a nice quite Inverness lad did the trick

Telfer’s methods haven’t proved popular with all his charges. He might have been a chemistry teacher, but his language wouldn’t pass muster in the classroom as he prepared teams to do battle through getting them psyched up – even if it meant the risk of being physically assaulted by one of his players in the process.

Another Borders great, Colin Deans, told me of one afternoon when the less-than-sunny Jim was embroiled in a furious altercation with an unexpected adversary.

Deans said: “I remember going on a 1980 development tour to France and we were beaten in our first game, with the forwards not doing themselves justice, and Jim went through us like a dose of salts and the next 10 days were the hardest of my life.

“Later on the trip, we came up against a French Barbarians side, which comprised the boys who had won the 1975 Grand Slam, and Jim knew it was going to be a really tough contest. So he started winding up one of our guys, George Mackie, who was a nice big lad from Inverness, who didn’t have a malicious bone in his body.

“Well, after Jim was finished, George was flinging punches at him in the changing room. It was totally out of character for him, because he was one of life’s gentle giants, but Jim had decided he needed battlers against the French and, by the time George walked out on to the field, he was fighting mad and ready to run through a brick wall.

“Jim just smiled at that stage. He rolled with the punches and seemed happy about the reaction he had provoked. It told you about the qualities he brought to the job.”

Taking the non-Rocky road to Grand Slam glory

Telfer returned battered, bruised and bewildered from the 1983 Lions sojourn to New Zealand, where his team was thrashed 4-0 and the Scot was at his lowest ebb. Asked about his future involvement in coaching, he replied: “Is there life afer death?”

Yet, within a few months, he was back in the thick of orchestrating heroics as his players surged to the first Grand Slam for the SRU’s finest in 59 years.

He had absorbed psychological lessons from his All Black mauling and dragged himself back up off the canvas. Prior to meeting Ireland in the 1984 Five Nations, he showed his squad what he regarded as a motivational video. It wasn’t Rocky or Chariots of Fire, but rather an X-rated rugby exhibition, which featured the Borders being pummelled 30-9 by New Zealand during the previous autumn.

As John Rutherford said: “We knew the All Blacks were a tougher proposition than the Irish, but it was an extremely effective wake-up call to those of us sitting there.

“It was typical Jim: he always wanted us to learn from our mistakes and the best way we ciould really do that was to confront them head-on.”

The Scots won 32-9, a demolition job in anyone’s language. And there was no let-up as they approached their final tussle with the French, who were also aiming for the Slam.

Many neutrals viewed Les Bleus as unbeatable. Yes and the Titanic was unsinkable.

A grand achievement which stirred the blood

Telfer plotted, planned and provided momentum in the build-up to the juddering clash. But he could also be phlegmatic when it suited him and he avoided placing unnecessary pressure on his men by talking up the French in advance.

Behind the scenes, though, he was driving home the message that, while Serge Blanco, Jerome Gallion & Co had mesmerising talent, they were also prone to losing their discipline – and that proved one of the major factors in a memorable contrast of styles.

France led 6-3 at the interval, but gradually fell on the wrong side on referee Winston Jones. With Peter Dods levelling matters at 9-9, the visitors started indulging in cheap shots, behaving like the Borgias on a bad night, and the tide turned.

Jim Calder’s try was the coup de grace and the hosts were cheered to the rafters by the Murrayfield crowd after sealing their 21-12 success.

It hadn’t been the prettiest of victories and Scotland were dead on their feet at the end, but as Telfer said: “This was never a day for fancy dans. They have been magnificent.”

So too, had been the coach who sparked this renaissance in his homeland.

Pursuing the right path and Redpath to success

Bryan Redpath was one of the outstanding performers of his generation in the No 9 berth and his son Cameron made his debut for Scotland at Twickenham on Saturday.

The family were one of many to benefit from the Telfer influence on Melrose RFC: an organisation in a little village which punched way above its weight for decades.

As Bryan recalled: “I will never forget when he used to take us for training on Sunday mornings. There would always be somebody or other throwing up, having taken too much beer the night before, and Jim would lay into him about standards.

“More than once, he was asked to tone down his language as people left the church beside the ground [at The Greenyards]. But I knew his sole motivation was to make me and my team mates better and keep pushing us on to discover new levels.

“I remember, on the day Scotland were leaving for the 2003 Rugby World Cup, I went along to a birthday party with my son, Cameron. It was for his friend, Harvey Ferguson, the son of Jason and grandson of Sir Alex Ferguson.

“Alex told me he remembered hearing Jim Telfer had once said to his players: ‘You are not just doing this for your team mates, you are doing this for your country’.

“Alex said that he had really liked that quote and I can recall thinking: ‘You are just like him. Two great Scotland coaches.”