There was nothing unusual about the Wednesday morning in March 1996 when I headed into work at the Scotsman building in Edinburgh city centre.

As 9am became 10am, and ideas, schedules and forward planning conferences were drawn up, nobody could imagine what was unfolding in a little school 35 miles away.

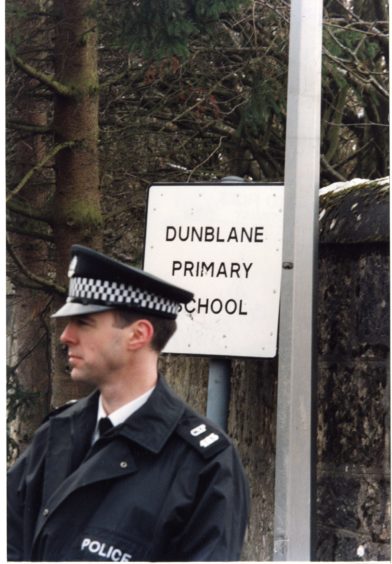

In these days, there were no Twitter feeds or WhatsApp devices to issue alerts of breaking stories – just the sound of phones ringing in the office with hints that something had happened in or around the premises of Dunblane Primary School.

The initial reports suggested there might have been a minibus crash.

Then there was the word from several members of a the public about a large police and emergency service presence descending on the town and they were all travelling in the one direction.

And eventually, during the next few hours, we were all confronted by the visceral horror of the mass murder of children and one of their teachers by an armed gunman which become everybody’s focus in an environment where everything else seemed trivial.

News of Dunblane massacre sent shockwaves round the world

These incidents are mercifully rare even in the United States, where there have been several occasions, including at Virginia Tech in 2007 and Sandy Hook in 2012 when students and staff have been killed on campus in shooting tragedies.

But the very notion of somebody behaving in the fashion of 43-year-old Thomas Hamilton seemed unthinkable – which is one reason why the details of how he scraped ice off the window of his van at his home in Kent Road in Stirling as the prelude to journeying to Dunblane with a weapons cache, chilled the blood.

As the hours passed, police confirmed how he had entered the school gymnasium with four legally-owned handguns, prior to firing rapidly, randomly, indiscriminately at shocked little boys and girls and those who were looking after them.

There was heroism from staff members who found themselves in the midst of Britain’s worst-ever mass shooting.

PE teacher, Eileen Harrild, was injured in her arms and chest, but managed to stumble into a store cupboard with several injured children.

She escaped the fate of Gwen Mayor, the teacher of the Primary 1 class, who was shot and killed instantly.

The other adult in attendance, Mary Blake, a supervisory assistant, sustained wounds in the head and both legs but somehow managed to make her way to the same cupboard with a number of the children in front of her.

This was like a vision of hell in a small primary school

Nobody could have predicted the fashion in which Hamilton behaved that day.

Although he was regarded as something of an “oddball” by other people in the community, no-one believed he was remotely capable of inflicting such terror on innocent victims as he did before killing himself inside the school property.

In the mobile classroom closest to the fire exit where Hamilton had been standing, Catherine Gordon instructed her Primary 7 pupils to get down onto the floor just before he fired nine bullets into the classroom, striking books and equipment.

It was one of a string of close escapes for some of those in the school.

Yet, by the time he took his own life, 16 children and a teacher were dead and 15 others were injured.

No other story has ever evoked such grievous emotions

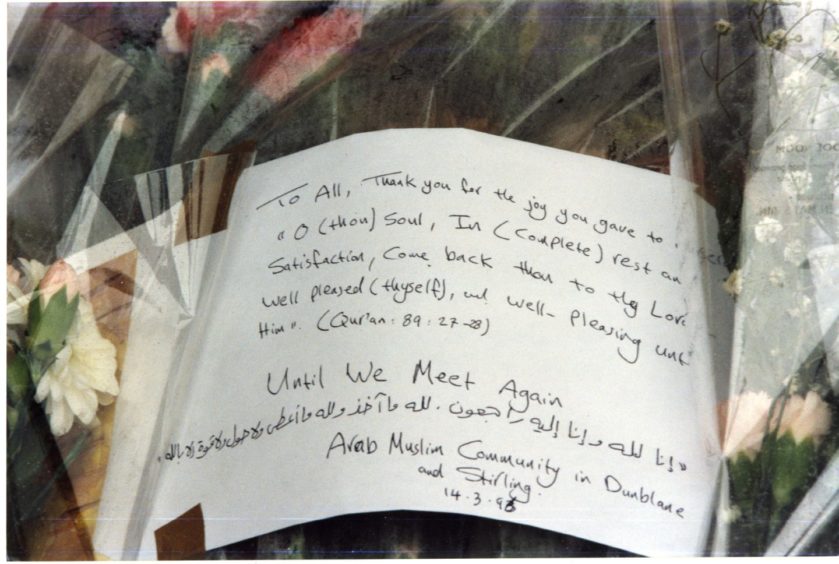

There was grief and revulsion throughout Scotland in the aftermath of the massacre.

Even for those of us who had covered the Piper Alpha disaster and the Lockerbie bombing in 1988, the events at Dunblane seemed the essence of wickedness and the haunted expression on the faces and tears in the eyes of people both in Dunblane and everywhere else in the days ahead testified to the conflicting emotions.

Scotland on Sunday news editor William Paul recalled his reaction on that terrible morning and in the days ahead as the scale of the atrocity became clear.

He said: “The tip-off calls began to trickle into the office early on [Wednesday], that there had been an incident at Dunblane Primary school, with police cars everywhere, ambulances…all the evidence that this was something big.

“I dispatched a reporting team before knowing the full facts, and had a feeling of physical sickness as the truth emerged.

“The violent deaths of young children was an unimaginable tragedy, but there was a need to suppress emotion and adopt a professional attitude to get the job done.

“However, emotion took over again in the front page image of a snowdrop, with its head bowed in apparent grief and bewilderment.”

A determination to ensure it never happened again

Numbness and incomprehension were the feelings of those in Dunblane who tried to pick up the pieces of their lives in the ensuing months and years.

A quarter of a century later, most of the pupils who were at the school – including a young Andy and Jamie Murray – have progressed with their lives and privately voiced a prayer for those who weren’t so fortunate.

Those of us who covered any aspect of the story always felt we were intruding on the grief of others.

Even on a trip to Dunblane in 2006, the mention of those terrible events a decade earlier, prompted the response from one resident: “Not this again. Are we going to be one of those places which is forever linked to something bad?”

That hasn’t happened. Yet the words of one of the locals in the aftermath testified to how Hamilton’s killing spree had rocked them to the core.

Dawn Smith, a nursery school assistant, had cared for five of the children who perished on an ordinary morning in their classrooms.

She said: “They were all beautiful wee things. Some of the youngest at the school who survived thought that the gunfire came from Power Rangers or Ninja Turtles or superheroes. They didn’t know until the end how black the real world can be.”

The outcome of the Cullen inquiry

Lord Cullen had already led the inquiry into the Piper Alpha disaster, which claimed the lives of 167 men in the North Sea in July 1988.

And he investigated thoroughly the circumstances which had led to the murder of 16 children and one of their teachers at Dunblane Primary.

His subsequent report recommended that the Government introduce tighter controls on handgun ownership and consider whether an outright ban on private ownership [of such weapons] would be in the public interest.

It also urged changes in the level of security measures at Scottish schools and the vetting of people who worked with children under the age of 18.

The Home Affairs Select Committee agreed with the need for restrictions on gun ownership, but stated that a handgun ban was not appropriate.

Campaigners took their own steps

Determined to press for tougher regulations, the Gun Control Network was founded in the aftermath of the massacre and was supported by some parents of the victims of the Dunblane and the [1987] Hungerford shootings.

Bereaved families and their friends also initiated a campaign to ban private gun ownership and this became known as the Snowdrop Petition.

Later, in August 1996, thousands of us gathered at Murrayfield for a rugby contest between Scotland and the Barbarians to raise money for the Dunblane Fund.

Understandably, it was a poignant occasion, one where the minute’s silence at the beginning meant you couldn’t hear a pin drop at the ground, despite the presence of a crowd of more than 32,000 spectators.

And although no sporting contest could transcend the grief, the Dunblane International – which the visitors won 48-45 – was a festival of rugby and a celebration of life.

Ultimately, in incredibly difficult circumstances, it was a fitting and worthwhile memorial to the 17 innocents who died at the hands of a crazed gunman.

Andy Murray only spoke about it more than 20 years later

Three-time major tennis champion, Sir Andy Murray, revealed in a documentary in 2019 that he and his family had known the man who committed the Dunblane killings.

The tennis star, who was just eight years old at the time, spoke of how he had previously shared a car with Thomas Hamilton and attended his children’s clubs.

Murray and his older brother Jamie were in lessons in March 1996 when Hamilton burst into the gym hall armed with four handguns.

The Scot opened up about the tragedy for the first time in the Amazon Prime Video documentary Andy Murray: Resurfacing, and explained how tennis became an ‘escape.’

He told film-maker Olivia Cappuccini: “You asked me a while ago why tennis was important to me. Obviously I had the thing that happened at Dunblane.

“I am sure for all the kids there it would be difficult for different reasons. The fact we knew the guy, we went to his kids club, [the fact] he had been in our car, we had driven and dropped him off at train stations and things.

“My feeling towards tennis is that it’s an escape for me in some ways. Because all of these things are stuff that I have bottled up.”

Conversation