The brother of Fife doctor Harry Goodsir made the discovery which gave the first clue to the fate of the crew of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror.

Robert Anstruther Goodsir’s eyewitness account then drifted into obscurity after being written in a newspaper in Australia in 1880 under the pseudonym ‘An Arctic Man of Two Voyages’.

Robert was seen as a minor part in the story…until now.

What happened to the Franklin expedition?

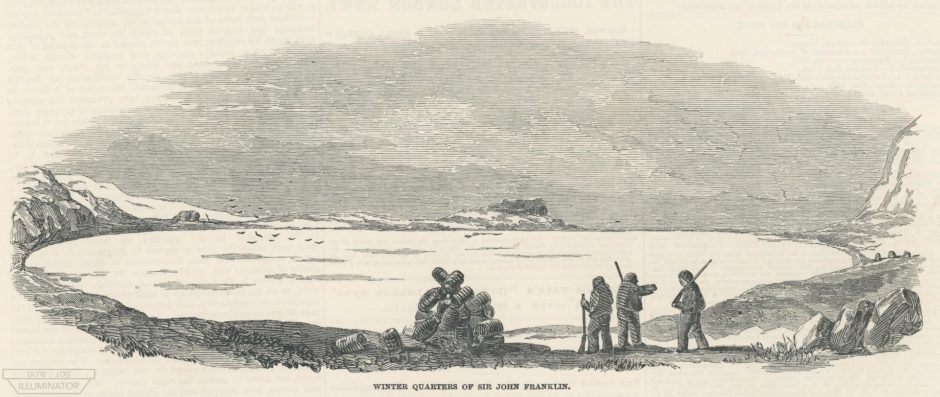

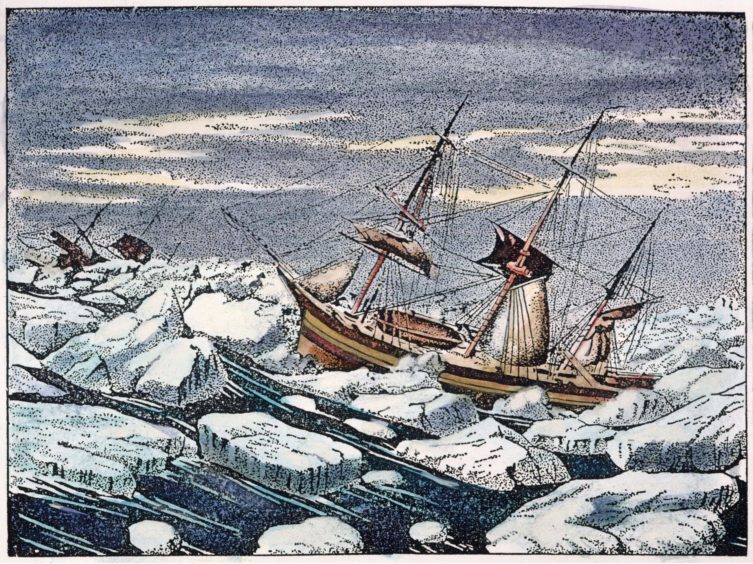

Arctic veteran Sir John Franklin departed Britain in 1845 in command of two ships, the HMS Terror and HMS Erebus, to seek the fabled Northwest Passage.

Then they vanished without a trace including Dr Harry Goodsir who was the assistant surgeon and naturalist on HMS Erebus.

The fate of the Franklin expedition fascinated Victorians and inspired a steady stream of books and the Ridley Scott TV series on BBC Two.

Robert was among the many friends, relations, and members of the public that were concerned at the lack of news of the expedition after four years.

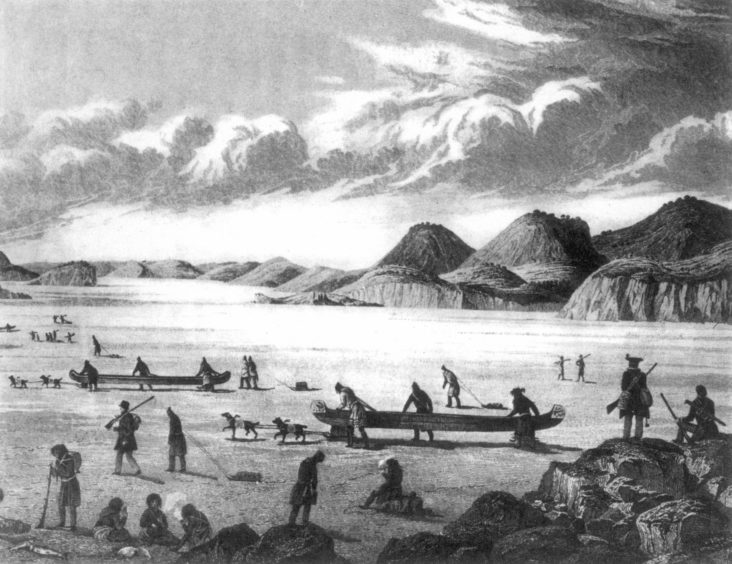

Robert first sailed to the Arctic with Dundee whaler Advice in 1849 under the command of William Penny from Peterhead.

He joined Penny again in 1850 as surgeon on an Admiralty-backed Franklin search expedition which included the ships Lady Franklin and Sophia.

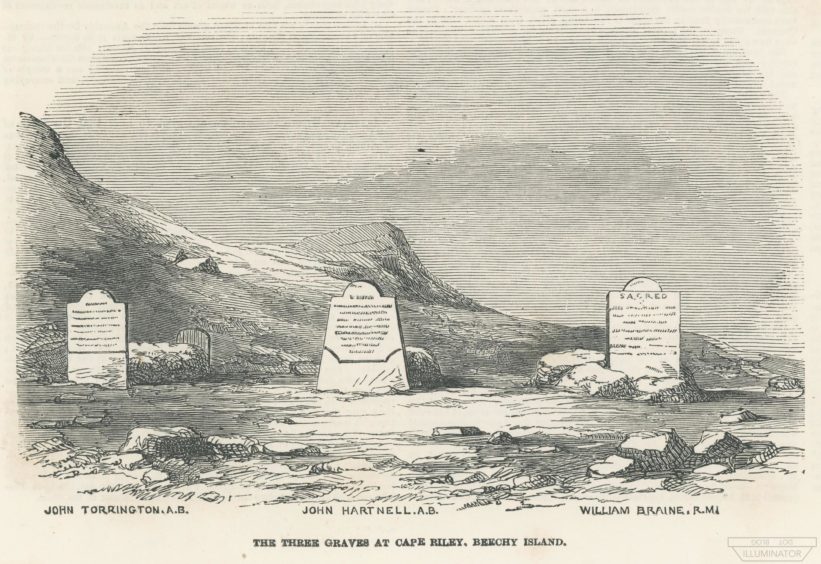

Here they found three graves at Beechey Island from 1846 proving Franklin’s presence.

Robert had landed there with a team including Aberdonian John Stuart, assistant surgeon of the Lady Franklin; and Johan Carl Christian Petersen, who was a celebrated Danish explorer and interpreter for the Penny expedition.

Thirty years on, writing in The Australasian newspaper, Robert gave his account of what happened.

In it, he described the “half-hour of half hope” on Beechey Island, before he discovered a cairn of empty meat tins and the “ghastly truth” of three graves.

Excitement was at fever beat during rescue mission

“The quick eye of Petersen had seen something, and his shrill cry in broken English of ‘Caneesterres! Caneesterres!’ made our hearts beat faster with the knowledge that the scent was again breast high,” he recalled.

“Quickly breasting the loose and shifting shingle, we saw before us a neatly-built pyramidal cairn of canisters or meat tins, about 9ft high, a little broken at the corners by the bears or from other causes, but still evidently carefully constructed.

“Our excitement was at fever beat, for scarce a second elapsed between Petersen’s first exclamation and his next more startling cry of ‘Mans! Mans!’, his Scandinavian features all aglow, and his blue eyes almost starting from their sockets.

“Almost at the instant of his utterance I had descried three dark objects about a mile off, where the spit merged into the talus at the foot of the cliffs of the northern side of Beechey Island.

“God! Can I ever forget the strange feelings of that half-hour of half hope – the deep excitement with which I started off at headlong speed towards these dark objects, all too willing to be cheated by the thought that the Dane’s vision was quicker than mine, and that they were, indeed, men?

“I recollect dashing down my gun ere I had gone many yards; I recollect tearing madly at the strap of my telescope (a rare Dollond, the gift of ever good and kind Lady Franklin), and of recklessly casting it on the stones.

“Ammunition belts and pouches were cast aside.

“I recollect slackening pace for a second or two to get rid of my heavy pea coat and sealskin cap until I could speed more freely along, with the panting Petersen well behind.

“I recollect noting as I sped along the thousand articles with which the beach was bestrewn, pieces of rope, fragments of timber, scraps of iron, but I did not pause, though I remember me well of gasping out to myself the word – wrecked.

“I recollect that soon after starting I became satisfied that the objects towards which we were so anxiously pressing could not be men.

“I recollect that my next idea was that they were huts, and deluding myself into the fond fancy that a filmy smoke rose from one or all of them.

“I recollect how soon this idea also proved a mockery, and that as I quickly, stride by stride, drew closer and still closer to the dark objects, the ghastly truth dawned upon me that it was three graves that I at last stood beside.

“Three heavy slabs of wood shaped like humble headstones, painted black, their backs to me, and on the other side the low, oblong-rounded mounds, underneath which three at least of those we were in search of were peacefully lying.”

Eyewitness account was forgotten for 138 years

Robert said the “still, quiet desolation of all around me was unbroken, save by the quickly-advancing steps of Petersen crunching over the gravel”.

He said: “I dreaded seeing the name of one near and dear to me who had sailed in the Erebus.”

He finally plucked up the courage to look at the names on the grave.

His brother’s name was not one of them.

He said: “After the names, my next glance was at the dates: from these I could judge that in this bay the Erebus and Terror had lain during the winter of 1845-6.”

Robert never once mentions Harry’s name and his eyewitness account has never been included in any of the books or papers about the search for Franklin since being published in Australia in 1880.

No first-hand account of the discovery of the Beechey graves was available until the text of the article was found in 2018 by independent researcher Alison Freebairn.

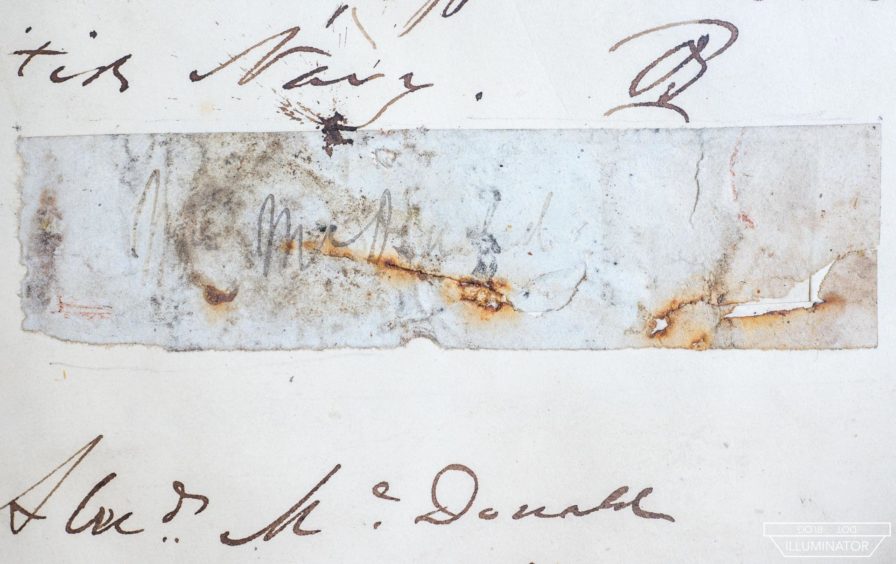

The text matched up with fragments which were known to have been part of a draft manuscript written by Robert that was exhibited by the Scottish Geographical Society in Perth after his death in 1895.

“He wrote this 30 years after it happened and he gets some minor details wrong, but it’s an incredibly vivid and important account,” said Alison.

“I knew the original was out there somewhere, but I had no evidence that it had been published anywhere. So it was an incredible feeling when I found it after a long search on the Australian archive site Trove.

“Robert was a very gifted writer and, if the cards had fallen more favourably for him, I’m sure he would have had a brilliant career as an author.”

Robert’s younger brother Archibald was dying

Alison said Robert was faced with an impossible dilemma before going in search of the lost Franklin expedition of 1845.

His youngest brother Archibald was dying and Harry was missing in the Arctic.

“The story of the Goodsir family is one of almost relentless tragedy,” said Alison.

“Robert had gone up to Dundee to find a whaling captain that would take him up to Lancaster Sound so that he could try to help find Harry.

“He fell in with William Penny who had already done some searching off his own back, and who had been in touch with Lady Jane Franklin.

“When Penny agreed to hire him as surgeon for the 1849 voyage to the Arctic, Robert had to make a painful decision.

“His younger brother Archie was dying of tuberculosis.

“He could stay in Edinburgh with Archie, or he could leave and try to find Harry.

“He was absolutely determined to find Harry.

“So he left Archie, went up to Dundee, got on the Advice, which left on March 8.

“They left Stromness on their final stop on March 17 and poor Archie died on March 20.

“Robert’s letters home from the Advice make it clear that he would write home but he knew what Archie’s fate must be.

“He came home, and went almost directly back out again in 1850 on the ship paid for by Lady Franklin.

“As well as being the first person to find the graves, he also found lots of scraps of paper left by the Franklin expedition around Beechey Island – including one with the signature of Alexander McDonald, the assistant surgeon on HMS Terror, who was from Laurencekirk.”

The Goodsir family died not knowing Harry’s fate

Robert, his brother Joseph, and his sister Jane were all still alive in 1869 when an Inuit guide led explorers to a spot on King William Island where a shallow grave contained the almost complete skeleton of an officer.

The remains were sent home to the UK, where the renowned biologist Thomas Henry Huxley wrongly identified them as Lieutenant Henry Le Vesconte.

A new forensic analysis of the skeleton in 2011 – which was buried in the Franklin Memorial in Greenwich – found a likely match in Harry.

“The Goodsir family all died not knowing Harry’s fate, even though it’s likely his skeleton was in the UK and interred in Greenwich during some of their lifetimes,” said Alison.

Alison is currently working on compiling a biography of Robert’s life and times, as well as researching other aspects of the Franklin Expedition on her blog.

Michael Tracy, of Chicago, Illinois, one of Harry Goodsir’s closest living relations, has spent over a decade researching the distant medical branch of the family.

“Dr Robert Anstruther Goodsir has always held a great interest in my continuing search to uncover more of the story of my family,” he said.

“Robert’s main objective on his two Arctic search expeditions aboard the Advice and Lady Franklin, were to find his long lost brother, Harry.

“As the Advice, a Dundee whaler, was readied to sail in March 1849, the hopes of the entire Goodsir family rested on the shoulders of young Robert.

“He was not a passive observer during the voyage and made strong efforts to participate in various activities, as the whaler travelled to the Arctic, among them joining a boat crew in which he was able to experience the same risks and fears as the crewmen.

“The first expedition proved unsuccessful without detecting any trace of Sir John Franklin.

“Shortly after returning home, Robert Goodsir appealed to Lady Jane Franklin’s ‘good offices’ to aid him in obtaining an appointment in any subsequent expedition during January of 1850.

“He was already preparing for the next expedition and met with Charles Green, the famous balloonist about the possibility of deploying balloons in aiding the expedition in the search and rescue mission.

“Goodsir received his appointment in April of 1850 as surgeon of Lady Franklin under the command of William Penny who he corresponded with as well.

“On his second Arctic voyage, Robert Goodsir even took his brother’s letters with him.

“Captain Penny sent a small side-party, Dr Goodsir among them, to reconnoitre the shore of Erebus and Terror Bay when they discovered a neatly-built pyramidal cairn of meat tins and the three graves.”

Robert was the Lion of the Seasons

When the winter of 1850-51 set in, the crew of the Lady Franklin wintered at Assistance Harbour, near the entrance to Wellington Channel and it was reported that the young doctor ‘had a rare fund of stories of the way in which they contrived to forget the monotony of an Arctic winter’.

Robert led a search party across Cornwallis Island in 1851 – into what was unknown territory to Europeans at that time, but was home to Inuit communities.

He was away for 53 days and covered a total of 428 miles.

Unfortunately, he found no traces of the Franklin Expedition, and neither did any of the other sledge teams that season.

“In the quest to find his long lost brother, Robert Goodsir exemplified perseverance and determination,” said Michael.

“It is with great respect and pride to recount Dr Robert Goodsir’s participation in these two Arctic search and recovery expeditions as well as his life story.

“He was by all accounts ‘the Lion of the Seasons’.”