Some of California’s most dangerous prisoners were trained by Tayside engineers to make sand bags at San Quentin.

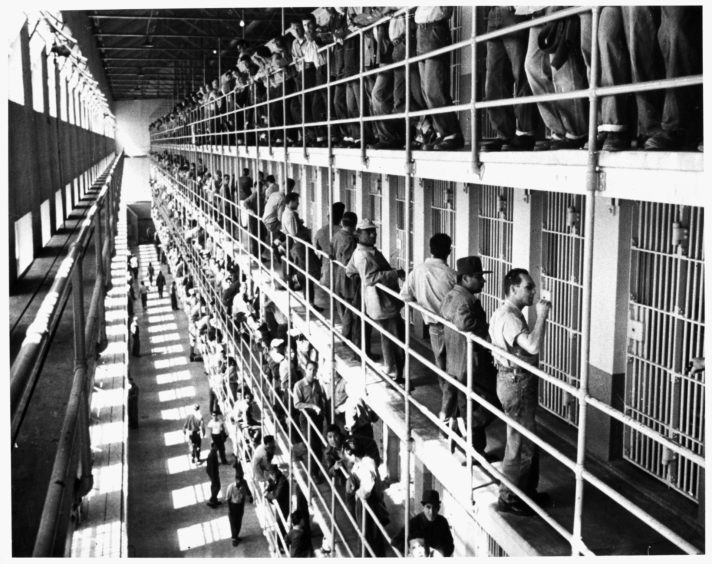

The jute mill was the prison’s most detested industry and was equipped with machinery from the Monifieth Foundry of James F Low and Co Ltd.

Opened in 1882 as a means to offset the cost of running the prison, the 85 looms in the mill turned out 30,000 jute bags a day.

In its first year alone the mill’s products alone recouped half the prison’s annual costs.

Jute was imported from India and Indonesia, and brought to San Francisco, and from there to San Quentin by a paddle wheel steamer called The Caroline.

Known to many thousands of inmates as a “hell hole”, the mill became the focal point for infection spread by the dust, resulting in mass mutinies by the prisoners.

Yet it never failed to show a profit.

Timbers crashed to the ground

The prison was working on an order for 4.5 million sand bags for the war effort in Korea when fire wiped out the mill 70 years ago which caused $3 million in damage.

Inmate Salvador Mosqueda was working in the sewing section and had just finished a cigarette which he carelessly threw to the floor nearby.

He noticed a small wisp of smoke coming from a nearby pile of finished sacks and decided to throw more bags on the pile in the hope of smothering and hiding the smoke.

He also tried to stamp on the pile.

A larger fire quickly broke out, and spread rapidly in the 69-year old wooden structure when 700 of the mill’s 850 workers were returning from lunch.

At the height of the fire, the flames and smoke were visible for eight miles.

As its timbers crashed to the ground, guards abandoned their towers to join the inmates in fighting the blaze, which threatened for a time to engulf the whole prison.

There were no deaths or serious injuries during the fire, although 13 inmates and guards suffered relatively minor burns and smoke inhalation.

The jute mill at San Quentin was replaced by a cotton textile mill in 1956 which eventually ceased production in 1969.

Local firms exported machinery globally

Local historian Dr Kenneth Baxter from the University of Dundee said: “It’s always interesting to find Dundee and Angus built textile machinery turning up across the world.

“While the area is famous for exporting its jute and flax products across the globe, the building of the machines that powered the textile industry also made a major contribution to the local industrial economy and is an important part of our industrial history.

“While obviously many customers were local, local engineering firms exported machinery to customers across the globe as this example shows.”

James F Low and Co Ltd was set up around the beginning of the 19th century by James Low and Robert Fairweather at Monifieth.

The manufacturing premises covered 15 acres in the centre of the town.

The firm, which produced the first locally made carding machine for flax tow in 1815, grew as machine spinning spread throughout Tayside.

By the 1880s there were 300 workers employed at the Monifieth Foundry, producing a range of machines for the processing and spinning of jute, flax, hemp and other similar fibres, not only for local textile spinning concerns but for customers throughout the world.

In 1924, the Low family sold their interest to John Shaw & Sons (Wolverhampton) Ltd, manufacturers and merchants.

By the early 1930s the company was in serious financial trouble and in 1933 was taken over by a Dundee syndicate headed by Joseph Johnstone Barrie of Charles Barrie and Sons, shipowners and insurance brokers.

The company’s fortunes were restored during the Second World War when the foundry was almost completely turned over to the production of bombs, machine tools and aircraft components.

The return of the men from the armed services, found changes being made in the Foundry, due to the recession in the jute and textile industry.

Operations were transformed to the production of building contractors plant, such as dumper trucks and concrete mixers.

The firm then assumed the name of Rob Roy and was owned and managed by a family from India.

Sadly by the early 1980’s all production had ceased and the site was condemned for demolition to be cleared away to make space for a shopping precinct.

Memories of the jute industry in Monifieth

Margaret Copland, president of Monifieth Local History Society, said the San Quentin connection with the town was “absolutely fascinating”.

“I have always considered that Monifieth was here because of the church history, but only developed from a sleepy village when the Low family established their foundry in an open field, in what is now the High Street around 1800,” she said.

“The establishment of mills and factories generated the demise of handling weavers working from home.

“The need for spinning, weaving and machinery associated with the linen and jute production, was recognised by the Low family and the foundry by the sea flourished.

“Between the wars the foundry employed almost 2,000 people with some travelling daily by rail or bus to Monifieth.

“Today there are people who remember living in housing provided for foundry workers including Foundry Terrace and the tenements fondly named Poddlie Raw.

“Those who served their engineering apprenticeship in James F Low’s foundry were held in high regard and found employment throughout the world.

“To this day there are those who come forward with pride to tell of their connections with the big foundry in Monifieth with industrial premises covering 15 acres.

“The years following the change of ownership and operations under the trade name of Rob Roy engineering were successful before its eventual closure and demolition of the buildings, ended industrial engineering in Monifieth, making employees look for work in other areas.

“This did cause families to drift apart, and created the start of a different community.

“Without the ancient history of the church and Low’s Foundry there would not be Monifieth as we know it today.”

Taking Low’s machinery to the world

Kenneth Miln served an engineering apprenticeship with James F Low and Co Ltd and went to India to install and commission machinery at mills in the Calcutta area.

He served over six years between India and Pakistan in the jute industry, over 16 years in Africa and three years as works manager of Ogilvy Bros jute mill in Kirriemuir.

He also helped to set up the jute machines in Verdant Works in Dundee.

He said: “Fully experienced Low’s journeymen would have gone out to San Quentin to install, commission and train inmates in the operation and maintenance of jute mill machinery.

“This would have proven quite a difficult task as apart from a communications constraint due to a language-accent difference, inmates selected for operative duties would require good manual dexterity.

“Many people would have been surprised to learn of Low’s links with San Quentin.

“Most Dundee folk were well aware of Low’s links with India and Europe, but links with a prison in the USA were virtually unknown at that time.

“San Quentin’s prison jute mill must rank as one of the strangest places to which Low’s machinery was shipped.

“However, Low’s also shipped jute mill machinery to Burma, Thailand, Kenya and South Africa.

“Training San Quentin inmates would have entailed a significant degree of patience, perseverance and understanding on the part of Low’s engineers and inmates alike.

“Low’s engineers would have had to train a squad of inmates in the techniques of day-to-day maintenance and long frequency planned maintenance procedures.

“In addition, training in the proper use of engineering tools would have been necessary.”

Closure ripped the heart out of Monifieth

Mr Miln said it was a good company to work for and job opportunities were numerous both in Scotland and overseas on completion of a Low’s apprenticeship.

“A major drawback was an almost total lack of briefing on the environment and culture of countries to which an engineer would be sent to install machinery,” he said.

“We were supplied with a tool-box, air-tickets and details of the machinery to be installed and first-timers were on their own after they got their health jabs!”

Mr Miln said he was lucky having been brought up in India because he spoke Hindi almost fluently although some engineers would have struggled.

“A significant part of Monifieth was lost when Low’s closed-down its textile machinery manufacturing business and switched to civil-engineering equipment, with subsequent detrimental affect on the local community,” he concluded.

“Also, a major link with the ‘outside world’ was lost.”

Johnny Cash performed a famous concert in San Quentin in 1969

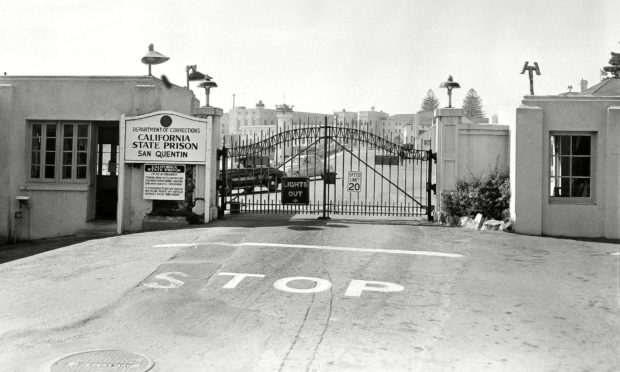

San Quentin had started out in the 1840s as a prison ship anchored close to the north shore of San Francisco Bay.

But when the number of prisoners being sent to the ship became too large a more permanent prison was built onshore, next to where the ship had been anchored.

Over the years this had expanded until, by 1969, it covered 40 acres and held almost 4,000 men, including many of the most dangerous criminals in the United States, and employing more than 1,000 guards and other staff.

US country legend Johnny Cash campaigned hard to improve conditions for prisoners and performed many concerts inside prisons.

One of the most famous of these was at San Quentin State Prison in 1969.

A crew from Granada Television in the UK filmed the concert for broadcast on television.