It was a meeting between an ambitious young American with plans for a grand polar expedition – and one of Scotland’s greatest exports, whose name has become synonymous with philanthropy.

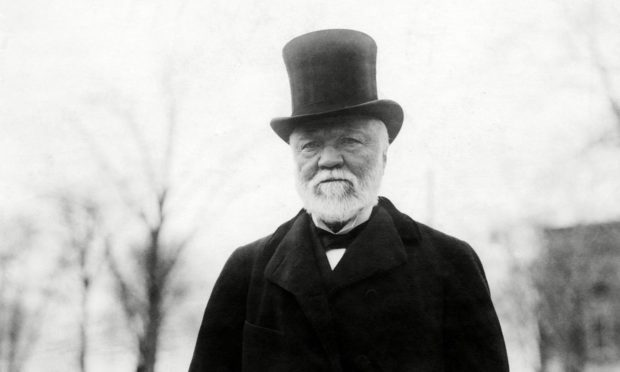

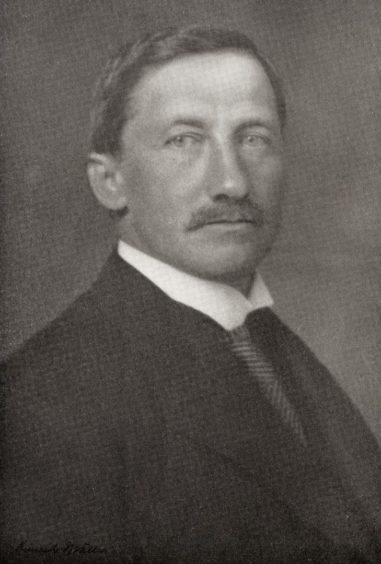

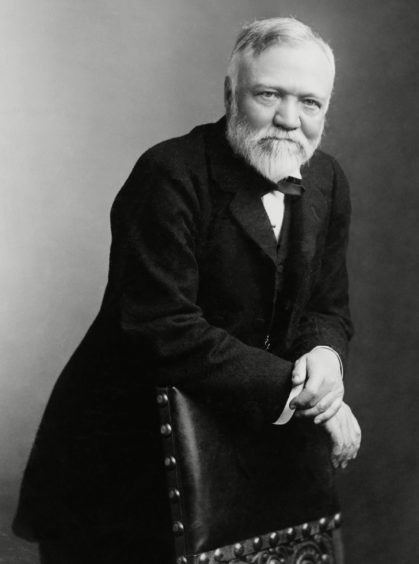

Yet there was nothing charitable in the air when Dr Frederick Cook, who was determined to raise money to finance an Antarctic odyssey, convened with Dunfermline-born Andrew Carnegie at the palatial Union League club on the corner of Fifth Avenue and Thirty-ninth street in Manhattan early in 1897.

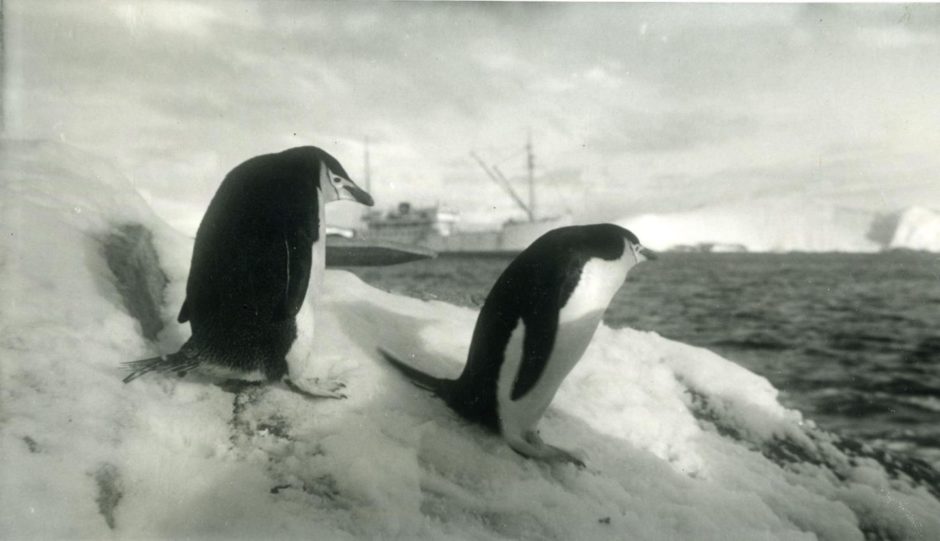

It was one of the first chapters in a sprawling story of adventure and adversity; one which led to the vessel Belgica being stuck fast in the ice of the Bellinghausen sea, as the prelude to the crew enduring months of darkness and being plagued by a horrific illness while they descended into madness.

The setting could hardly been more different when Cook, a man whose career was bedevilled by scandal, such as when he claimed to have become the first man to reach the North Pole in 1908, shook hands with Carnegie, and the pair began to discuss the venture in the lavish Tiffany-windowed building.

In the end, Cook’s later infamy, which earned him a long jail sentence, overshadowed his brilliance aboard the Belgica in the company of the ship’s first mate, a young Norwegian called Roald Amundsen, whose name is forever enshrined in the chronicles as the man who beat Captain Scott to the pole.

But that was far in the future when the passionate Cook and the pragmatic Carnegie sat down to chew over the brass tacks of the proposal.

A bond was forged between the two

The details of the meetings between this odd couple have been documented in Madhouse at the End of the Earth, a new book by acclaimed writer Julian Sancton, which documents the extraordinary turbulent life of Cook, part PT Barnum, part Walter Mitty with a soupcon of Indiana Jones in his make-up.

Whatever his faults and foibles, he established a dynamic friendship with Amundsen even as the pair plotted a desperate, last-ditch – and audacious – escape from their prolonged white hell around the Belgica.

Mr Sancton has outlined how Cook had charisma to burn and, initially at least, made a positive impression on the multi-millionaire Scottish expatriate.

He said: “Given Carnegie’s reputation as a cut-throat businessman, it surprised Cook to see him show genuine enthusiasm for the project.

“Perhaps, the once penniless Scottish immigrant recognised that he and Cook were cut from the same threadbare cloth, both citizens of Europe, who found that America imposed no limit on their ambitions.

“The two spoke amiably of polar exploration for an hour after which Carnegie got up, shook Cook’s hand, and said: ‘Doctor, I would like to get interested in your ice business. See me next Monday or write [to] me.

“Carnegie was challenging Cook to show how the expedition might be profitable, evidently not convinced by Cook’s allusion to a potential Antarctic gold rush. At their second meeting, in the corner of a lavish club room redolent of cigar smoke, pleasantries were put aside.

“Cook knew that he could not rely on charm and tall tales this time.”

The whole plan was put on ice

When he joined up again with Carnegie, he had prepared a detailed explanation of why the Antarctic mission deserved support. It would help science, it would boost mankind’s knowledge of the world, it would shed light on a previously uncharted region…and so, he passionately laid out his case.

Yet, just as the doctor’s pitch was reaching a crescendo, a fellow club member approached Carnegie and “rudely interrupted” the conversation. It was a pivotal moment. In a trice, the moment had passed.

As Sancton related: “Carnegie rose and walked Cook to the stairs. He said: ‘Doctor, there is so much to be done in this world nearer by. Three miles above is all the ice we will ever need.’

“Cook was devastated. He now realised that when Carnegie had expressed interest in the ‘ice business’, he had literally meant the business of ice – the possibility of harvesting Antarctica’s glaciers for the mundane purposes of refrigeration and chilling cocktails.”

It was a crushing blow for Cook, but he refused to become too downhearted. Interest in the frozen continent had risen significantly since the Sixth International Geographical Congress of 1895 called for its urgent exploration.

And then, while he was perusing the New York Sun on August 6 1897, he noticed a news item about the imminent departure of an Antarctic expedition from – of all places – Belgium.

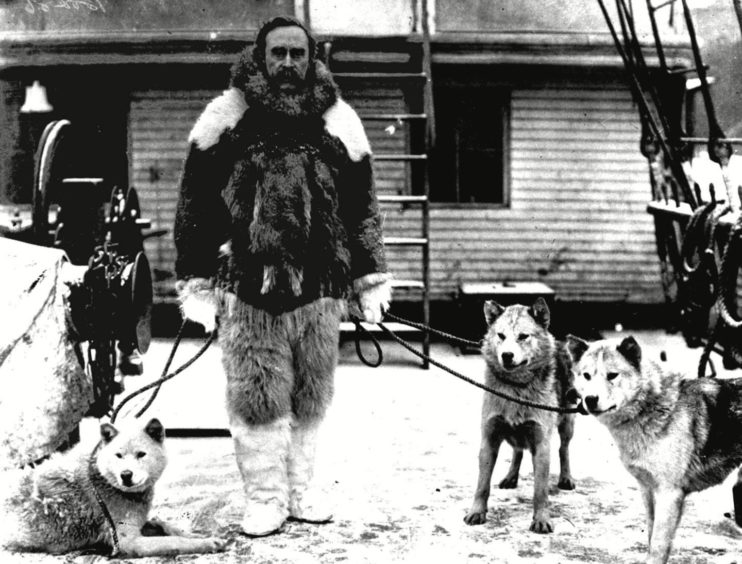

This was his opportunity. And, just a few weeks later, he was on his way with 13 Belgians, ten foreigners and two cats named Nansen and Sverdrup.

The trip soon turned into a nightmare

If Cook was thrilled that he was finally realising his dream, his elation quickly turned turned to trepidation. Almost anything that could go wrong did go wrong for Adrien de Gerlache’s doomed crusade in the months ahead.

The Belgica broke down in the North Sea and was forced to put into Ostend for repairs. Two crewmen deserted there and two more crewmen went ashore without permission, returning to the vessel drunk out of their skulls.

But while Cook was in his element, the litany of misfortunes piled up. On reaching Montevideo in Uruguay, the cook was sacked and a Swedish replacement was hired. On the voyage between Montevideo and Punta Arenas, Chile, the engineer allowed the boiler to run dry and was dismissed.

There were further disciplinary problems at Punta Arenas resulting in the Chilean Navy being asked to intervene. The Swedish cook and three Belgian sailors were dismissed and, by the stage the Belgica finally departed for the Antarctic, it was significantly undermanned.

Matters went from bad to worse

Sancton’s book vividly conveys the confusion and chaos which built up as the Belgica continued on its ill-starred exodus into the remote wilderness.

The crew was, for the most part, inexperienced and more enthusiastic than knowledgeable about the enterprise which they had undertaken from the safety of Europe. So it was hardly a surprise when, soon after crossing the Antarctic Circle on February 15 1898, the ship became wedged in pack ice.

The crew had not prepared for the prospect of wintering in Antarctica and the obdurate Gerlache forbade the crew from digesting the penguin and seal meat which had been stockpiled because he himself hated eating it.

As a result, scurvy became a problem and the travails and tragedies stacked up to the stage where madness began to set in.

Magnetician Emile Danco perished on June 5 1898, then morale worsened after the death of Nansen, one of the ship’s cats, a few weeks later. The situation had turned into a ticking timebomb of insanity.

One attempt to cut a mile-long escape canal to the open sea – a hazardous undertaking at the best of times, let alone with scurvy-blighted sailors – failed when a random change of wind closed the channel.

The desperate situation cried out for bold and decisive leadership. Which is where Cook and Amundsen took centre stage in the drama.

Salvation was on the horizon

By July 22, command of the ship was taken on by the duo, because the hapless De Gerlache was too ill to carry on issuing his mostly futile instructions. What had seemed like a noble plan in Belgium had been transformed into a horrific chapter of incompetence and mismanagement.

Cook insisted that the men ate the penguin and seal meat, which ensured that the crew rapidly recovered from the scurvy.

Sancton wrote: “His air of optimism was the keystone of his treatment plan. ‘When at all seriously afflicted’, he wrote, ‘the men felt they would surely die and to combat this spirit of abject hopelessness was my most difficult task’.

“The doctor turned his shipmates’ eyes away from the dark chasm of anguish into which they stared throughout the night and towards the light at the horizon, which lingered a few minutes longer every day, heralding the sun’s imminent return.”

The dire prospect of a second winter in Antarctica spurred the men on in their efforts to extricate Belgica from its plight and Cook and Amundsen worked heroically and unstintingly to rescue themselves and their colleagues.

Their efforts and powers of persuasion worked. On Valentine’s Day in 1899, Belgica was finally freed from the ice, although it was another month before she was able to set sail for Punta Arenas, where she arrived on March 28.

A hero’s welcome for returning home

Belgica was repaired in Punta Arenas, then sailed for Buenos Aires in Argentina and, although there were little grounds for jubilation, given the heavy toll which the expedition had suffered, she ventured home and arrived in Antwerp on November 5, sparking national celebrations in Belgium.

It was Cook’s crowning moment. While Amundsen took immediate steps to organise his own expeditions and eventually, more than a decade later, a party of five, led by this redoubtable character, became the first to successfully reach the South Pole on December 14 1911, his Belgica confrere was heading in a starkly different direction – downwards.

From the poles to the prison cell

Cook and his compatriot, Robert Peary, subsequently became involved in a furious war of words over their rival claims to have reached the North Pole.

In December 1909, a commission at the University of Copenhagen, after examining evidence which had been submitted by Cook, ruled that his records did not contain proof of the explorer’s claims.

This sparked consternation and and the New York Times asserted: “He will count for ever among the greatest impostors of the world.”

Peary refused to submit any of his documents for review by a third party, and for decades the National Geographic Society, which held his papers, refused researchers access to them. He, too, was discredited.

In 1919, Cook became involved in promoting start-up oil companies in Fort Worth, but he and 24 other individuals were subsequently indicted in a federal crackdown on fraudulent schemes.

Inmate #23118 was not a typical con

Three of his employees pleaded guilty, but Cook insisted on his innocence and went to trial. He was charged with paying dividends from stock sales, rather than from profits and the jury found him guilty on 14 counts of fraud.

He was sentenced to 14 years in prison and though his attorney appealed the verdict, the conviction was upheld.

Amundsen, who believed he owed his life to Cook’s extrication of the Belgica, visited him several times and the doctor was eventually pardoned by President Franklin D Roosevelt in 1940, ten years after his release and shortly before his death of a cerebral haemorrhage.

But one suspects that Andrew Carnegie was right to have been wary of this mercurial but controversial figure.

Madhouse at the End of the Earth by Julian Sancton is published by WH Allen.