It seems a very long time ago, but Andy Murray has been part of the tennis landscape since he was a teenager, gaining applause from Sir Sean Connery at Wimbledon, and blazing an idiosyncratic trail.

Even before his appearances on Centre Court and his gradual elevation from a promising youngster on the junior circuit to a fully-fledged Grand Slam champion with three major victories, two Olympic gold medals, a Davis Cup success and the global No 1 ranking on his CV, the Dunblane maestro was being touted by his peers and even courted by other sports.

However, when the opportunity to play football at Ibrox presented itself, barely before he had entered his teens, the Scot preferred to concentrate on transforming himself into a lawn ranger, restlessly travelling the globe in pursuit of future conquests at Roland Garros and Flushing Meadow.

I recall meeting him at Craiglockhart in Edinburgh with his mother, Judy, who was rightly anxious about her son flying to the United States just a couple of weeks after the 9/11 atrocity in New York in 2001.

But Murray, forever his own man, cussed, obstinate and determined to pursue his ambitions on the grand stage rather than be a big fish in a small pond, made the journey to the US and kept working away during these formative years with the philosophy that genius is an infinite capacity for taking pains.

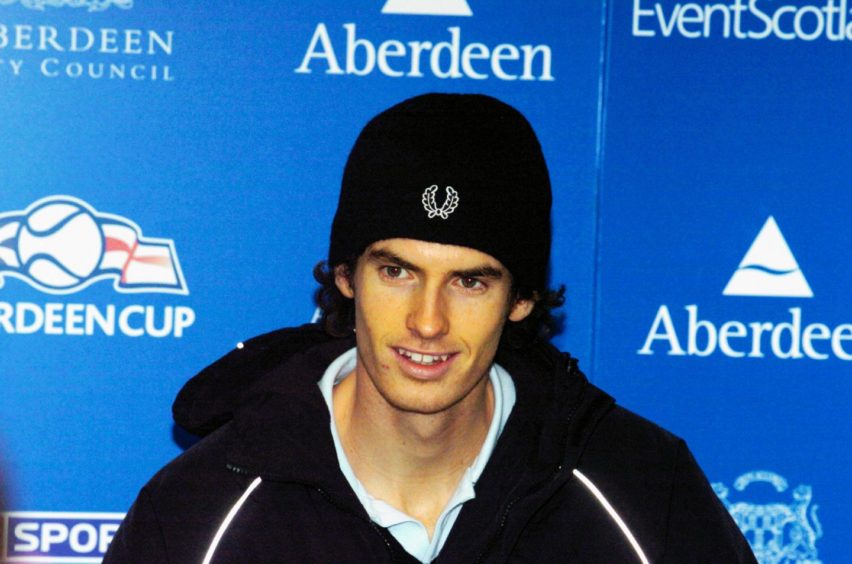

And that same dedication to duty was in evidence when Murray appeared in Scotland v England events in 2005 and 2006, and tackled the likes of Greg Rusedski at the former Aberdeen Exhibition and Conference Centre.

The contests were battles of Britain

In the same year that the Dunblane wunderkind rose from outside the world’s top 400 to 65, he competed in the Aberdeen Cup and impressed spectators with a sparkling variety of ground strokes and compelling determination to chase down every shot as if it was a matter of life and death.

The tournament had Scotland going toe-to-toe with their England rivals and was held twice in a bid to help attract the Davis Cup to Scotland: an ambition which was eventually realised when the event was held in Glasgow where battling brothers, Andy and Jamie, bowled over the Saltire-waving crowds.

There were contests in both singles and doubles and male and female junior players also took part, with one women’s player on each of the teams.

Furthermore, with the exception of the ‘headline’ ties, between the two captains, Murray and Rusedski, the rubbers were only two sets long, with a tie-break subsequently used to decide the outcome.

And, in his first-ever meeting with Rusedski, the gangly 18-year-old defeated his older rival in the final to earn Scotland a 4½ to 2½ win.

Murray never looked back after that

It was a genuine changing of the guard moment, and, during the next couple of years, Murray was gaining the upper hand over Tim Henman as well and inexorably taking his place at the summit of British tennis.

Even at that stage, his desire and hunger, allied to his prodigious talent and tenacity in chasing a ball into the Twilight Zone if it was required, stamped him out as a genuine international-class performer.

And his coach, Leon Smith, was understandably delighted with the manner in which Murray was making the transition from aspirant to achiever.

He can be as good as he wants to be

Smith, by no means one of life’s cock-eyed optimists, was effervescent when he talked about Murray’s potential to lock horns in the future with the likes of Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovik.

“How good can he be? Well, there is simply no reason why he can’t be a match for the very best,” said Smith. “The most important point is that Andrew himself accepts that he is currently on the steepest kind of learning curve in an ultra-competitive environment. The great thing is it doesn’t faze him.”

That much was obvious to those who followed his progress. Murray positively thrived on the no-pain, no-gain mindset, seemed immune to the tedium of enduring a diet of airport-and-hotel-room check-ins and, perhaps most crucially, was in full possession of an ingrained belief in his own abilities.

No wonder he was the subject of so much positive attention from his fellow Scots, who appreciated that, whenever he was digging himself out of scrapes and predicaments, the scale of Murray’s rage could be terrifying.

And he also had the knack for living up to P G Wodehouse’s famous assertion that it was never difficult to distinguish between a Scotsman with a grievance and a ray of sunshine.

Professionalism was in his DNA

He said in 2005: “In plain terms, this isn’t supposed to be fun. No, this is my job, my business for the next 10 or 15 years and I have to be 100% professional in my attitude because the rivalry out there, particularly from the old Eastern bloc nations is incredible.

“Basically, I have noticed that their players have this tremendous hunger and desire to succeed and a lot of that is down to the fact they simply don’t enjoy the type of luxuries which we take for granted in Britain.

“It stares you in the face and the only way to beat these guys is to be as aggressive and as much of a perfectionist as you can possibly can be.”

The 2006 event was a damp squib

If the inaugural Aberdeen Cup was a success in showcasing the prowess of the Murray brothers, there was nothing uplifting about the 2006 tournament.

On the plus side, Scotland successfully defended their title at the AECC, but this only happened amid trenchant criticism from Andy about the quality of the court surface and what he regarded as inflated ticket prices.

The 19-year-old steered his compatriots to a second title as the home side thrashed England 6½-1. But Murray, who was suffering from a persistent ankle problem, questioned the state of the Aberdeen facilities.

“The court is dangerous to play on,” he said. “It’s slippy and the line judges are very close to the back, so I could have quite easily twisted my ankle.”

Tennis has to be more accessible

He was equally scathing about what he regarded as exorbitant ticket prices – £35 for adults and £17.50 for children – which were one of the reasons why the crowds were significantly smaller than they had been 12 months earlier.

Murray said: “The most important thing is to encourage the kids to come back and they need to bring ticket prices down. If they do that for kids, then it will be easier for adults to bring the kids along.

“Tennis is always classed as being a sort of upper-class sport, but it should not be like that all. The game should be for everybody, but ticket prices like this aren’t going to get that many kids playing tennis. It is very expensive to come to an exhibition match.

“And then, we also need more public courts in Scotland. I know that when I was younger the private tennis courts next to my house on a Saturday morning were empty. Nobody was playing and there were padlocks on them.

“These are the sorts of things we have to change to get youngsters playing the game and that is what I want to happen.”

These comments summed up Murray’s determination to speak out on social matters: and he has maintained that throughout his career, whether defending women players from critics or championing inclusivity.

But his words spelled the death knell for the Aberdeen Cup – or at least it did until the AECC was demolished and the P&J Live sprung to life.

Battle of the Brits set up in December

Andy Murray’s battle with injury has been one of the titanic struggles from any Scottish competitor. Knock him down and up he bounces. Give him a gloomy prognosis and watch him make the medics eat their words.

He’s the human embodiment of Zebedee from the Magic Roundabout and will be in action again when court action resumes at Wimbledon this week.

But, while his resolve has been admirable, there is a sense that the clock is ticking on his professional career and it could be that, just as he began to create magic in Aberdeen, he will bid adieu to his fanbase in the same city.

That’s because the Battle of the Brits is coming to the P&J Live on December 21 and 22, where the Murrays will be joined – in front of a substantial number of spectators – by the likes of British No 1 Dan Evans and Cameron Norrie, who reached the final of the men’s singles at Queens Club last week.

He’s one of Scotland’s greatest stars

Sometimes, a sports personality’s influence on his domain can be overstated.

Yet it’s impossible to downplay the impact which Andy Murray has made, boosted by his brother and his indefatigable mother, Judy, all of whom have grabbed the sport by the scruff of the neck in the last two decades.

If there are any more tilts at Grand Slam titles in the future, it will be another coup for a fellow who has transcended any number of obstacles. Indeed, it’s difficult to think of another individual who has shattered so many stereotypes.

In essence, he is British tennis for the 21st century, as immutably linked to the game as Frank Sinatra was with My Way or Clint Eastwood with Dirty Harry.

And it’s appropriate for somebody who has graced Aberdeen in the past and will do so again this winter that he has a granite streak all his own.