It’s a story that began with tolls and turnpikes, advanced to stagecoaches and trains, and continues to this day with the construction of the NC500 and ambitious proposals for space ports in the Highlands that owe more to Star Trek than Outlander.

Eric Simpson, who lives in Buckie and studied in Aberdeen, has long marvelled at how roads and bridges, tunnels and rail tracks were created in so many remote parts of the country.

As a youngster, he cycled to the far north of his homeland and began researching the often inventive, occasionally acrimonious fashion in which the Highlands were opened up to the world.

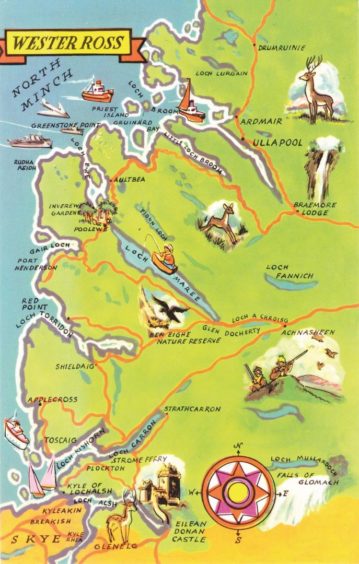

He has now produced a book, Highways to the Highlands, about the subject and it’s an absorbing, anecdote-laden account of how tourists, troops and hosts of other individuals have been travelling to Invernessshire, Wester Ross, Caithness and thence on to Scotland’s islands for hundreds of years.

His journey follows the Great North Road from Edinburgh to Inverness, continues into the most northerly parts of the Highlands and highlights the myriad changes that have happened during the often rapid transport revolution of the 20th Century.

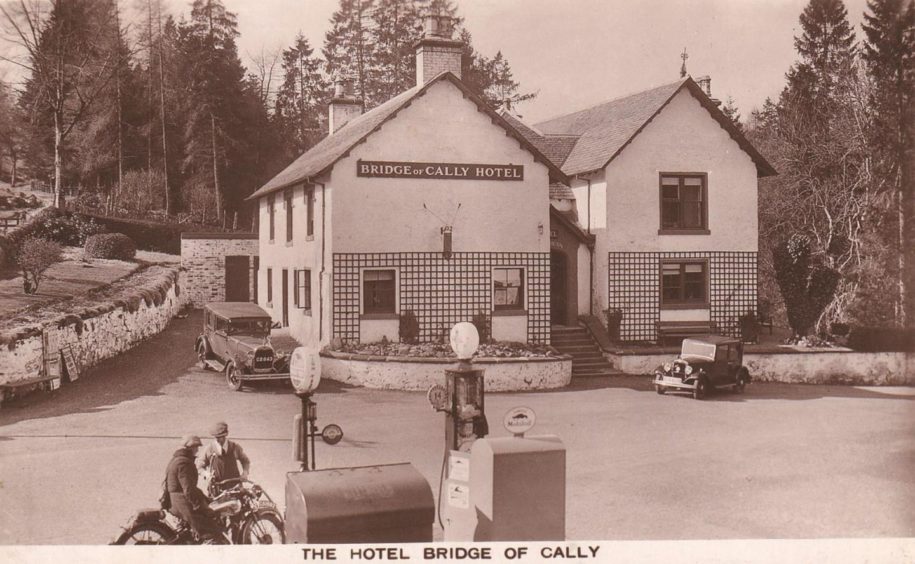

The author has brought together a collection of evocative old postcards and other images that hark back to a bygone age.

But he has also emphasised the innovation of so many of the Victorian trailblazers and, in particular, the remarkable work of Thomas Telford, whose bridge designs and constructions changed so many people’s lives.

Communities throughout Scotland have been boosted by improved links with their neighbours, but the public hasn’t always appreciated the expense involved and Eric has revealed details of the local stramashes that broke out when turnpike trusts were established in many places in the 19th Century.

These bodies were entitled to charge road users and, to this end, toll houses with gates or bars, otherwise known as turnpikes, were constructed.

However, these places were often detested by local residents, especially when impoverished citizens were informed by their masters that they would be charged tolls to go about their daily work.

Long before the poll tax prompted the same kind of direct action in the 1980s, the widespread response was: Can’t Pay, Won’t Pay.

As Eric said: “The installation of toll bars was met with many complaints and much grumbling about what seemed to be another form of taxation.

“While some people sought to avoid toll charges by seeking alternative routes, generally speaking, these charges were accepted, albeit reluctantly.

“However, there were occasional outbreaks of violence with attacks on toll keepers and the destruction of toll gates.

“Mobs destroyed a toll gate at Wick in 1827 and at Dunkeld in 1868, where riots erupted and the toll gates were tossed into the river.

“Toll houses could also suffer – one on the outskirts of Kirkcaldy was repeatedly pulled down by irate villagers.”

It was often a febrile situation, but the labours of pioneers such as Telford and John MacAdam – whose name has entered the English language – generated a huge amount of momentum at the start of the 19th Century.

Indeed, between 1803 and 1821, the workaholic Telford supervised a mammoth project in the Highlands and his works still survive today.

There was no end to this man’s industry, endeavour and enterprise. In 1801, Telford orchestrated a master plan to improve communications in the Highlands of Scotland, a massive project that was to last some 20 years.

It included the building of the Caledonian Canal along the Great Glen and total redesign of sections of the Crinan Canal, some 920 miles of new roads, more than 1,000 new bridges – including the Craigellachie Bridge over the River Spey in Moray – and extensive harbour improvements in such cities and towns as Aberdeen, Dundee, Peterhead, Wick, and Banff.

Telford also undertook highway works in the Scottish Lowlands, including 184 miles of new roads and numerous bridges, but it was his exertions in the north and north east that had the greatest impact on his homeland.

And they even had an influence on one of Britain’s most beloved authors.

Eric explained: “Birnam, on the southern side of Telford’s Tay Bridge, is largely a Victorian settlement that owed its growth to the adjacent railway station that was built in 1856.

“For seven years, the village was the railway’s northern terminus, which meant that travellers proceeding further into the Highlands had to transfer to a coach in Birnam, which was obviously to the benefit of the Birnam Hotel.

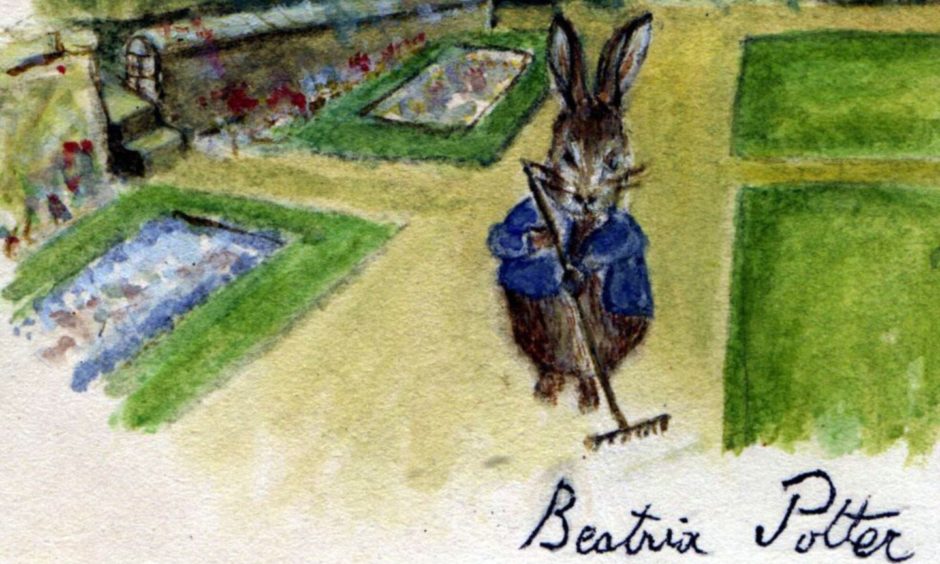

“As a young girl, Beatrix Potter was a holiday resident in the area and her memory is commemorated by a Beatrix Potter Garden.

“It was in Birnam that she wrote her first story, The Tale of Peter Rabbit.”

The rest, as they say, is history.

Eric has examined myriad different ventures and initiatives, some controversial, others which testified to the trailblazing nature of the Victorians as they made dramatic improvements to transport links.

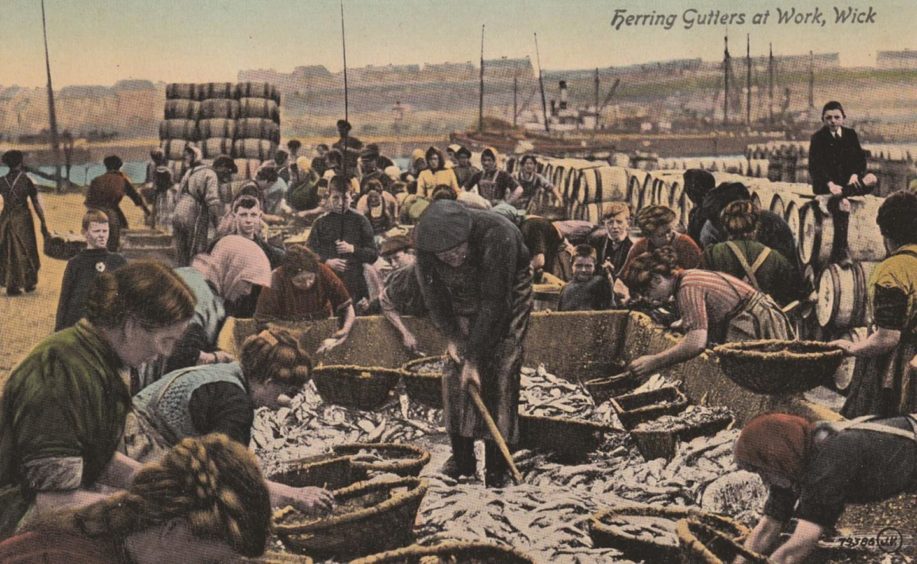

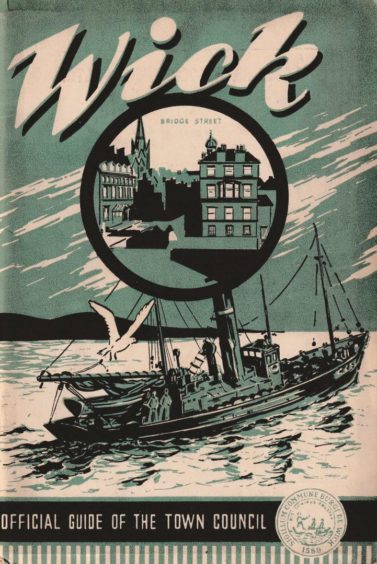

But he has also unearthed a string of quirky and unusual facts from the archives, such as a 1940s guidebook produced by Wick Town Council with a herring drifter on the front and the information that visitors could enjoy occasional music shows by German prisoners in a POW camp at Watten.

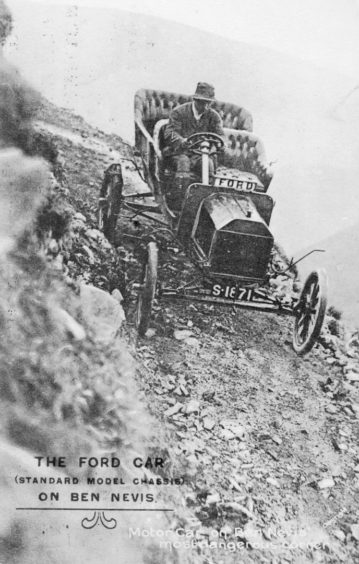

Then, there’s the dramatic and slightly terrifying picture of Henry Alexander in a Ford Model T car, descending Ben Nevis in 1911 on the pony track built to serve the observatory on Britain’s highest mountain.

He survived and the photograph exists as a testimony to his adventurous spirit.

All the same, there is one thing that hasn’t changed in the last 200 years: wherever there are roads, there will be unhappy travellers and drivers.

Complaints about the state of the Ballachulish to Tyndrum route continued into the 1920s and H V Morton, the best-selling author and journalist who toured the Highlands by car, regarded it as “the worst road in Scotland”.

Eric told us about why he has fallen in love with the north of Scotland and spent countless hours journeying throughout the region.

He said: “My fascination with the Highlands goes back a long way.

“Cycle tours in my schooldays and then being a keen hillwalker and Munro-bagger intensified my interest in the story of the Highlands and its people.

“My interest in the history of tourism brought me to consider why it developed and became such an important factor in the history of the Highlands, both for good and for ill.

“Tourists’ methods of transport were part and parcel of my story, and especially when travel became easier and cheaper with the arrival of steamboats and trains.

“I was inspired to write Highways to the Highlands because it allowed me to expand on two aspects of transport that had long fascinated me.

“The first was the era of turnpike roads and stagecoaches.

“This goes back to my childhood, when out in the family car, my father would point out: ‘There’s an old toll house’. In my day, books by Charles Dickens were in the school syllabus and, of course, stagecoach travel featured in his novels.

He continued: “The second came much later when, as a collector of old postcards, I would come across sepia 1930s-era postcards that depicted such things as ‘The New Glencoe Road’.

“It dawned on me that, when I was driving to the hills, I was still using these so-called ‘new roads’.

“That route is the cover image of my book, complete with one of the few remaining milestones.

“These take me back to the stagecoach era when they were compulsory features of the ‘new’ turnpike roads.

“As a walker, I was only too aware that many of the tracks I had trodden had a prior history as drove roads and military roads.”

But, as in so many other walks of life, nothing stands still.

The engineers of the 1920s and 1930s and those who followed them built on, and often over, the work of their predecessors.

Yet this is a story with no neat conclusion: if it’s not new rail networks or grandiose plans for bridges, there is talk of the Highlands becoming a base in the distant future for commercial space tourism.

Eric said: “Ever-increasing traffic in recent times has seen the building of even more impressive structures, like the two road bridges across the Firth of Forth, and, in the Highlands, new bridges for the Beauly, Cromarty and Dornoch Firths, and also at Ballachulish and Kylesku.

“Road improvement continues to this day with the parts of the Great North Road from Edinburgh to Inverness which are not yet dual carriageway now being dualled (along with similar schemes in Aberdenshire).

“And yet, as (Scottish author and the creator of Para Handy) Neil Munro once wrote: ‘This new road will some day be the Old Road too, with ghosts on it and memories.”

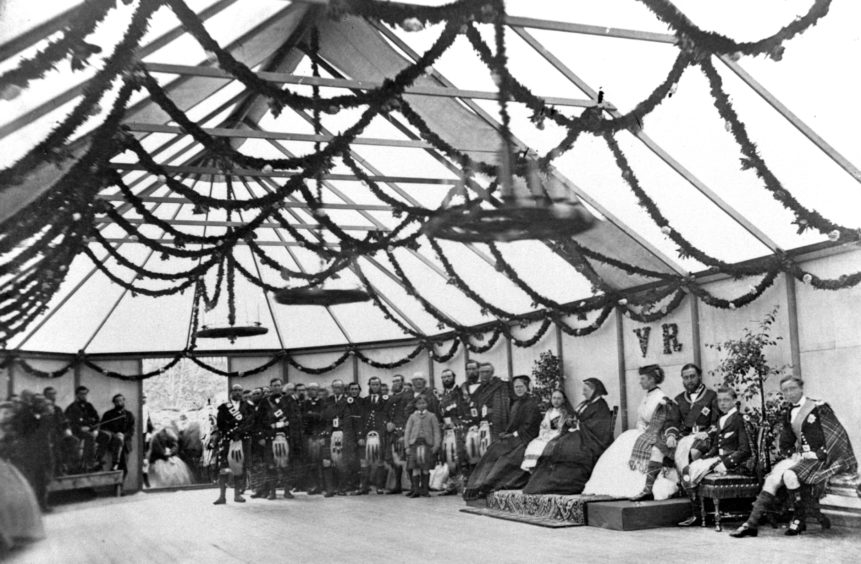

Queen Victoria was a regular visitor to the Highlands and north-east of Scotland in the early years of her reign.

But although she marvelled at the scenery and spectacular landscapes, not all her trips were memorable for the right reasons.

Eric has related how, in 1861, the monarch and Prince Albert, who were travelling incognito, paid a surprise visit to the Dalwhinnie Inn in the small village on the western end of what is now the Cairngorms National Park.

She later wrote in the journal Our Life in the Highlands: “Unfortunately, there was hardly anything to eat and there was only tea and two miserable starved chickens, without any potatoes! No pudding and no fun…”

Eric concluded: “Their servants fared even worse, getting only the scrawny remnants of the two meagre birds. This was the second to last of their ‘Great Expeditions’. Two months later, Albert was dead”.

- Highways to the Highlands is available to pre-order here.