His roots were in granite and his athletic talent made him one of the champions of the early Olympics.

Yet, despite a lustrous CV and a remarkable career, which spanned the birth of the modern Games in 1896 and the controversy surrounding Adolf Hitler and Jesse Owens in Berlin 40 years later, it’s doubtful if Lawson Robertson’s name is known at all these days in his homeland.

That’s sad, because there can’t be many more unusual routes to the Olympic heights than the fashion in which Aberdeen-born Robertson emigrated to the United States and became one of the leading figures in track and field athletics for the next 50 years.

His back story might tax the little grey cells of Hercule Poirot and the latter part of his career was consumed by rancour and recriminations after Robertson was embroiled in a selection scandal at the 1936 Games.

This event soon turned into a Nazi propaganda vehicle, but Owens transcended the noxious atmosphere with a series of stunning gold-medal-winning performances that silenced Hitler’s talk of Aryan supremacy.

His rise into the spotlight was a far cry from his early days, when Robertson demonstrated he was one of those fellows with a spring in his stride and a have-passport-will-travel mentality.

There is little information about how he ended up in America, as a young man, after being born in the Granite City in 1883.

Yet it’s impossible to ignore the impact he made in his domain during a distinguished career that encompassed everything from medal feats in the different jumping categories to being commemorated for posterity as a champion in the arcane world of the three-legged race.

The man who was known as Robbie to his friends and colleagues was a genuine one-off, an athlete who appeared on the inaugural Ripley’s Believe It or Not posters, which have become a part of millions of youngsters’ formative years in the States since 1918.

But if his origins were in the north-east of Scotland, he had a closer affinity to the many people with Irish ancestry whom he met across the Atlantic.

A genuine all-rounder

He was a member of – and a trainer for – the Irish American Athletic Club, and competed for the US Olympic team at the 1904 Olympics in St Louis, the now little-known 1906 Intercalated Games in Athens, and the more high-profile 1908 Olympics in London.

In the first of these events, he won the bronze medal in the standing high jump competition and was sixth in the 100m race.

Two years later, at the Intercalated Games, he secured the silver medal in the standing high jump contest and the bronze medal in the standing long jump.

But he was such a redoubtable all-rounder that there seemed to be no end to his exertions and the chances are that he was tired at the end of every day of competition.

In the 100m event, he finished fifth, he was sixth in the pentathlon and he participated in the 400m.

No wonder sections of the press regarded him as being a one-man team.

A return to Blighty

In the 100m at the 1908 Olympics, Robertson marked his return to Britain by winning his first-round heat in a time of 11.4 seconds.

But he subsequently lost a close race to countryman Nathaniel Cartmell, both runners clocking in at 11.2 seconds and the latter triumphing by just a few inches, which eliminated Robertson from advancing to the final.

On the same day as that semi-final loss, he was also knocked out in the preliminary heats of the 200m despite recording a second-place finish in his race. But he was never bothered or bewildered by these temporary travails.

On the contrary, his attitude to adversity was to stiffen the sinews and rise above it, regardless of how often he faced difficulties.

And that was never more obvious than his response to some traumatic events just a year after his trip back to the UK for the Games.

Incident could have killed him

On November 28 1909, Robertson was badly burned in a serious accident at Celtic Park in New York when a ladle of hot lead exploded in his face.

He had been preparing to pour the molten material for a 42-pound receptacle that was to be used in the shot put by Martin Sheridan and John Flanagan at the annual field day of the Second Regiment of the Irish Volunteers.

The shot was found to be a few ounces under weight so a hole was bored into it and the lead was poured inside to bring it to the required mark.

However, Robertson was standing over the ladle when some water dropped into the lead, causing an explosion that burned his face and neck.

The flesh about his eyes and face was burned and the lead burned his clothes.”

Newspaper account of Robertson’s accident

It could have been the end of his career – or worse – but expecting that would have been to underestimate the resilience and resolve of this steely individual.

One newspaper reported: “Fortunately, he had his eyes close tightly, and they were not injured. The flesh about his eyes and face was burned and the lead burned his clothes. He was grievously affected.”

However, even while he was being rushed to a doctor, the Irish American Athletic Club proceeded with the competition, and Martin Sheridan set a new world record with the very same weight, putting the shot 27ft 0.5in (8.24m), which was three-and-a-half inches further than the long-standing record of fellow Irishman James Mitchell.

And amazingly, or perhaps not in the circumstances, who do you think was present later that same evening to applaud Sheridan’s heroics than this determined Scottish fellow with a bandaged face?

An icon from another era

According to his 1910 trading card, it was reckoned he would “go down in athletic history as one of the greatest sprinters of the cinder path”.

In 1912, when Mike Murphy, the coach of the US Olympic track and field team fell ill, Robertson, in his capacity as assistant, took over the reins of the squad, which garnered an impressive haul of 16 out of a possible 32 gold medals.

He also served as assistant coach of the US Olympic team in 1920, and as the head coach for the next four consecutive Games in 1924, 1928, 1932 and 1936.

It was a CV that testified to his exalted reputation in American sporting circles and the media at the time were lavish in their praise for the many different qualities this fellow had in his armoury.

Believe it or not, he was a star

One declared: “Lawson Robertson has competed successfully as an athlete for Knickerbocker AC and later for the Irish-American AC and the Thirteenth Regiment. He has won national, metropolitan, Canadian and military athletic league championships in the sprints and jumps.

“He and Hary Hillman, who is now coach at Dartmouth University, were the greatest three-legged team that were ever strapped together.

“Their eleven seconds flat for 100 yards will stand for many a day. (And their exploits were featured in the first Ripley’s cartoon).

“In addition, as captain of the Irish-American AC for seven years, and under his charge, the Celts won every metropolitan, national and Canadian championship they tried for.”

Scandal struck at the Berlin Games

Robertson was regarded with respect and reverence but he became mired in controversy at the 1936 Olympics when he was criticised for the last-minute decision to withdraw Sam Stoller and Marty Glickman, the only two Jews on the American track team, from their events.

That led to widespread speculation that the US Olympic Committee chairman, Avery Brundage, had ordered the move to avoid further embarrassment to Hitler and cynically passed the blame on to Robertson, who made no public comment on the matter.

Given his track record and involvement in nurturing and encouraging the rise of such outstanding participants as Stoller and Glickman in the first place, it’s difficult to imagine Robertson would have willingly sacrificed the efforts of two of his colleagues for political reasons.

But Brundage, whose reputation has diminished in recent times, had previously convened with German government officials, although he was not allowed to meet Jewish sports leaders in the build-up to the Games.

When he returned, he reported, “I was given positive assurance in writing that there will be no discrimination against Jews. You can’t ask for more than that and I think the guarantee will be fulfilled.”

He fought furiously to prevent a US boycott of the competition. And he succeeded. But tensions simmered constantly behind the scenes.

Robertson hung out to dry

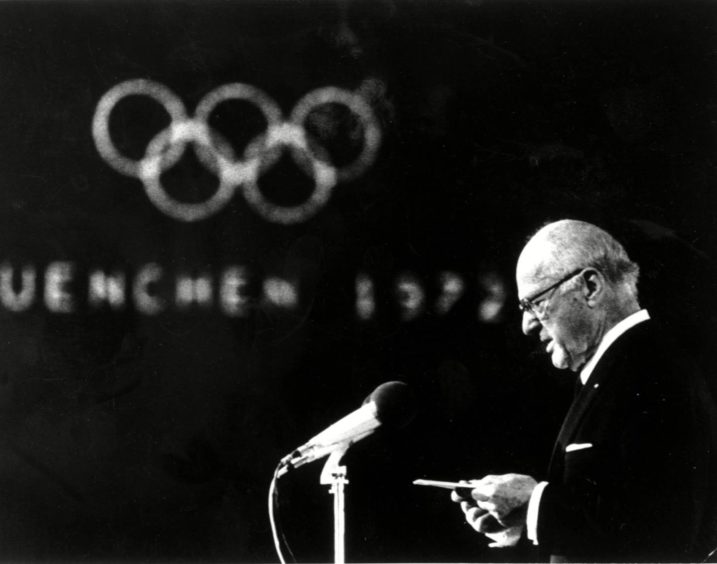

As the leader of America’s Olympic organisation, Brundage was elected to the IOC in the same year as the Berlin Games, quickly became a major figure in the movement and was elected IOC president in 1952.

He long outlasted Robertson, who died in Pennsylvania in 1951, at the age of 67. But the mystery of who did what and where at these notorious Games remains unanswered to this day.

However, in 1982, the writer Carolyn Marvin said: “The foundation of Brundage’s political world view was the proposition that Communism was an evil before which all other evils were insignificant.

“A collection of lesser themes basked in the reflected glory of the major one. These included Brundage’s admiration for Hitler’s apparent restoration of prosperity and order to Germany, his conception that those who did not work for a living in the United States were an anarchic human tide, (allied to his) suspicious anti-Semitism.”

In these circumstances, it seems desperately unfair that Robertson’s immense contribution to athletics has been forgotten.

Is it time for a re-evaluation?