It is one of the most famous sequences in movie history: Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffmann typing as if their lives depended on it, as Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein in All the President’s Men.

The film, which chronicled the investigative journalism of the duo that exposed the Watergate scandal and eventually sparked the resignation of White House incumbent Richard Nixon, highlighted a world before desktop and laptop computers when newspaper reporters, often with a cigarette dangling from their mouths, battered out the brass tacks of their latest exclusives and sent them to the sub-editors.

Nowadays, these devices might seem quaint, but one shouldn’t understate the impact they had when they were first produced on a commercial basis, after the original template had been patented in 1868 by Americans Christopher Latham Sholes, Frank Haven Hall, Carlos Glidden and Samuel W Soule in Milwaukee.

Some of these fellows reached an agreement with E Remington and Sons, who were, at that stage, more famous as a manufacturer of sewing machines, and the company began production of its inaugural typewriter model in March 1873 in New York.

This was a pivotal moment for generations of office workers and a new exhibition is being staged at the National Museum of Scotland to examine the social and technological impact of typewriters during the last 140-plus years, from early prototypes to the stylish mid-century models that are still in use today.

It’s an event that positively drips with nostalgia.

The Typewriter Revolution has been organised to chart the development of these iconic machines and explore their role in society, the arts and popular culture through the personal stories of those who designed, made and used them.

The extensive exhibition draws on National Museums Scotland’s significant typewriter collection, which includes an 1876 Sholes & Glidden typewriter that was the first to feature the now-established QWERTY keyboard; a 1950s electric machine that was used by Whisky Galore author Sir Compton Mackenzie; and the 1970s design icon, the Olivetti Valentine, which emerged from the Swinging Sixties.

Mackenzie wrote his famous novel, which later became one of the best-loved Ealing comedies, on Canna in the Inner Hebrides and the machine on which he crafted his whimsical account of the real-life sinking of the SS Politician during the Second World War is still in working order.

Many of these old devices were made to last and, just as his typewriter remained for decades at Canna House on the remote island, so Agatha Christie’s keyboard has been preserved at her home, Greenway in Devon.

The exhibition, which opens at the museum in Edinburgh this month, is intended to shed light on how these machines transformed office life for everybody from lawyers and journalists to civil servants and bankers.

They were a game-changer for anybody who was working with files and title deeds, newspaper reports and legal documents and, within a few years of their arrival, typing schools were established across Britain to capitalise on their potential.

Alison Taubman, principal curator of communications at National Museums Scotland, has no doubt about the seismic shift that happened as an increasing number of rival companies entered the market, created a diverse range of different models, and gradually produced portable and electronic typewriters as the 20th Century advanced.

Typing to Dundee and Aberdeen

She said: “The typewriter is a true icon. It revolutionised the workplace, it transformed communications and it inspired artists and writers.

“From the clatter of its keys to its unique aesthetic, the enduring romance surrounding the typewriter has earned it many devoted fans.

“This charming exhibition takes visitors on a journey from its inception as a curious piece of cutting-edge technology through its role as a crucial mainstay of the workplace right up to the present day, where it enjoys cult appeal.”

The often large and bulky early typewriters were first shipped across the Atlantic by E Remington & Sons throughout the 1870s.

At the outset, they were luxury devices that cost the equivalent of half the average annual salary: in short, they were out of reach to the ordinary household of the time.

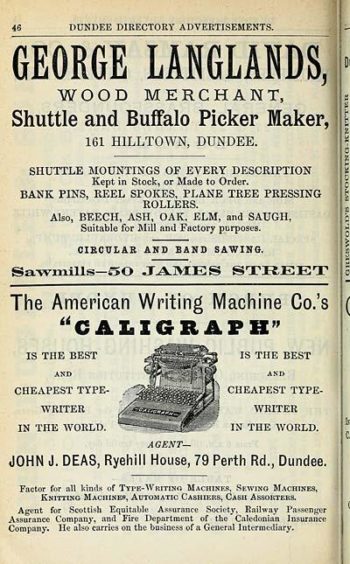

Sewing machine salesman John J Deas, who lived and worked in Dundee, was one of the most vocal enthusiasts of the new typing machines in Scotland.

He was particularly keen on the Caligraph model, which his extravagant posters proclaimed – twice – was “the best and cheapest typewriter in the world”.

Adverts for his business in Dundee and Aberdeen were equally bold and unambiguous. Mr Deas thought the typewriter was a magnificent invention, he was evangelical about spreading the word, and he told his customers loudly and proudly they would “do for the ink-bottle and pen what the sewing machine has done for the needle”.

Such promotion quickly reaped a rich dividend for those who sold the devices, who discovered a late-Victorian audience was thrilled by these technological gizmos.

Indeed, the final decade of the 19th Century was marked by a massive boom in the demand for typewriters as all manner of organisations began to realise their value.

By 1900 they had revolutionised the world of communications, both transforming office work and opening up new employment opportunities, especially for women.

And, while it might seem difficult to understand for a younger generation, there was a romance about the design of many of these typewriters.

They inspired many different novelists and artists, with prolific American Mark Twain among the first to use what he called a “new-fangled writing machine”.

Henry James relished the loud clacking of a Remington typewriter and found that his inspiration dried up whenever he upgraded to a quieter model.

Jack Kerouac typed out his magnum opus, On The Road, on a 36 metre-long manuscript because he wanted to write continuously in a dazzling stream of consciousness.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle even used the quirk that every brand of typewriter had its own unique stamp as a plot device in the Sherlock Holmes short story A Case of Identity and it also featured prominently in the Agatha Christie Poirot novel The ABC Murders.

In the late 1940s the Italian firm Olivetti opened a factory in the east end of Glasgow, later producing stylish models such as the Lexikon 80, and the portable Lettera 22, which were regarded as being at the cutting edge of design.

Typewriter technology advanced to include electric models from the 1920s before the rise in computers led to them gradually being phased out of most office spaces.

However, just as with many youngsters showing a renewed interest in vinyl records, cassette tapes and cine films, so an audience still exists for the old-style machines.

And, for them, the unique experience of writing on a typewriter and the enduring beauty of their design means that there is still a demand for these intricate machines among people of all ages and backgrounds.

- The Typewriter Revolution exhibition will be held at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh from Saturday July 24 to Sunday April 17 2022. Admission is free with pre-booked museum entry.