Covid has dashed hopes that vital evidence could be recovered from the sunken wrecks of HMS Terror and HMS Erebus, such as the ship’s logs or photographic images likely taken by Fife doctor Harry Goodsir.

Harry, who grew up in the East Neuk, was acting assistant surgeon and naturalist on Sir John Franklin’s polar expedition that aimed to seek the fabled Northwest Passage.

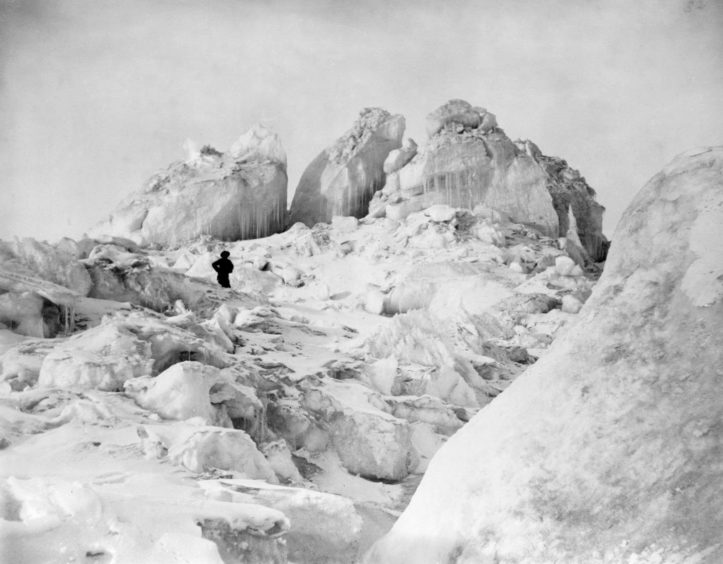

Terror and Erebus were abandoned in heavy sea ice in 1848 and the 105 men sought a route to safety across the frozen Arctic on foot.

Every one of them died in the endeavour.

It wasn’t until 2014 that a Canadian mission, equipped with all the latest marine archaeological equipment, located Erebus.

Terror was discovered two years later.

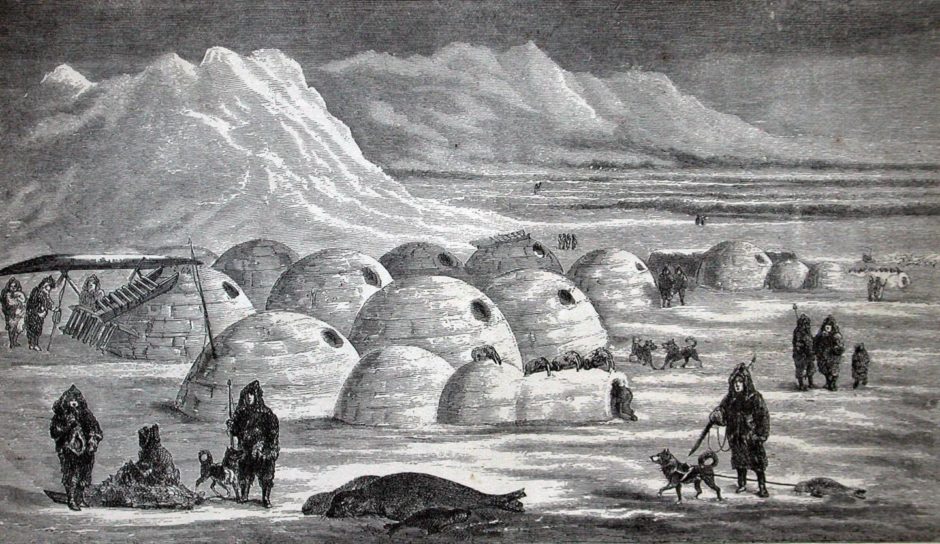

Teams from Parks Canada were due to continue work on Franklin’s lost ships next month, but the risk of exposing Inuit communities to Covid-19 was deemed too high.

Michael Tracy, of Chicago, Illinois, one of Harry’s closest living relations, has spent more than a decade researching the distant medical branch of the family.

“The decision to cancel this year’s dives on HMS Erebus and Terror is disappointing, to say the least,” he said.

“However, this is the right decision and in full accordance with the advice of public health experts.

“I have no doubt that when better times return the resumption of more detailed exploration of these two ships will captivate the imagination of those many followers of the Franklin expedition.

“Parks Canada dive team’s ROV footage has offered tantalising glimpses of the intact contents of the ships’ decks, but who is to say what may be discovered as underwater archaeologists piece together those contents of the individual crew members’ cabins – including that of my cousin, Harry Goodsir?

“It is a truly thrilling prospect!”

The pandemic had also prevented the 2020 dive season from taking place.

Access to the wrecks of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror in waters off King William Island in Nunavut is closed to all but local Inuit guardians keeping watch on the sites.

It’s a reminder of the dangers associated with seeking answers about what happened to Sir John Franklin and his crews more than 180 years ago.

The people who went in search of the lost Franklin Expedition – including Harry’s young brother Robert – faced terrible dangers in the Arctic.

Robert left Dundee on board the whaling ship Advice in 1849 under the command of William Penny from Peterhead.

He was faced with an impossible dilemma before going to sea.

His youngest brother, Archibald, was dying and Harry was missing in the Arctic.

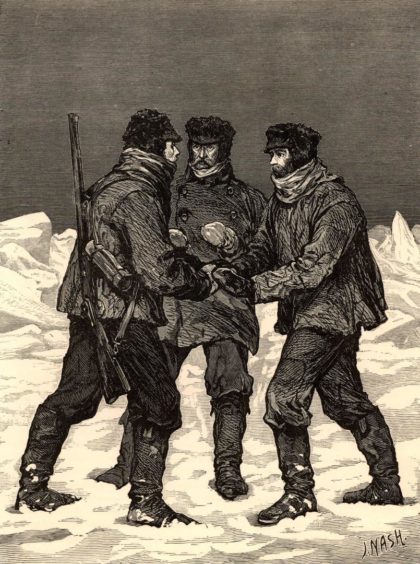

He was determined to find his brother and Franklin’s lost men but a terrible accident not long after the ship headed north almost cost Robert his life.

A letter written by Robert to his sister, Jane, from the Advice at Baffin Bay in August 1849 highlights how close he came to perishing on the Dundee ship.

“During such weather as this was, the helm is lashed down and none of the men remain on deck except two hands to keep a lookout, and even they take care to have themselves properly secured.

“I had just got down the companion and into the cabin, I was literally not 10 seconds off the deck, when a tremendous roller struck the ship with a report like thunder and threw her on her beam ends.

“I had at first no idea what it was but rushed on deck along with the Captain. Here nothing could be seen but wreck and destruction.

“The quarterdeck was literally swept of everything – bulwarks, stanchions, binnacle, wheel and tiller, one man was lying crushed beneath the wreck to windward, another stunned and unable to rise.

“The carpenter’s mate was seen floating on the binnacle away far astern and only seen for an instant before he sank. No earthly assistance could have been rendered to him.

“A fourth poor fellow must have been killed by the wreck before he was washed overboard, for nothing whatever was seen of him. It was altogether a frightful scene.

“I had to get the hurt men down into the cabin, which was the only place they could be taken to. It was nearly knee deep with water for the skylight was smashed and the sea had come down in volumes.

“Here, in utter darkness for the skylight had to be boarded over, and every surge of the ship sending water up to my waist, I had to put the poor fellows to rights with no assistance but the steward and the boy, both of them as little accustomed to the sea as myself. A good many of the men were seriously hurt but I got them all round.

“The ship was much damaged and they thought of putting back to Stromness but the weather moderating and our being so far to the westward determined them to hold on.

“It was most unfortunate that just when the sea struck her they were changing the watch which was the reason there were so many on deck.

“As it was I have much reason to be thankful to providence for my escape, for had I remained a minute longer on deck, nothing on Earth could have saved me.”

These letters are part of a collection of Goodsir family papers that have been in the care of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society in Perth since the late 19th Century.

These include Harry’s letters to his family from HMS Erebus before the expedition vanished, and a draft of Robert Goodsir’s book about his 1849 voyage on the Advice.

Many of these papers were displayed at an RSGS commemorative event held in May 1895 to mark the 50th anniversary of the Franklin expedition.

Robert joined Penny again in 1850 as surgeon on an Admiralty-backed Franklin search expedition that included the ships Lady Franklin and Sophia.

Here they found three graves at Beechey Island from 1846, proving Franklin’s presence.

Robert had landed there with a team including Aberdonian John Stuart, assistant surgeon of the Lady Franklin; and Johan Carl Christian Petersen, who was a celebrated Danish explorer and interpreter for the Penny expedition.

Independent researcher Alison Freebairn said: “Robert clearly had a very lucky escape here, although it’s tragic that two of his crewmates were not so lucky.

“He talks about the accident in his 1850 book, An Arctic Voyage to Baffin’s Bay and Lancaster Sound in Search of Friends With Sir John Franklin, but plays down his own heroism in the aftermath of it.

“It’s only in the letter home to his sister Jane that he paints this nightmarish picture of himself working in almost total darkness and waist deep in freezing water, trying to treat injured survivors with the ship still wildly pitching and rolling in the storm.

“Robert had never been to sea before he joined the Advice, but he would have been in no doubt about how dangerous this voyage could be – and his family would also have been acutely aware of this.

“They were from the East Neuk, and would have grown up seeing ships lost and families decimated by tragedies at sea.”

Alison said the story of the search for the Franklin Expedition is full of ships in peril and near-misses.

HMS Investigator was abandoned in 1853 after nearly three years trapped in the ice.

She was discovered by Parks Canada in 2010, sitting upright on the bottom of the Beaufort Sea, off Banks Island.

She said: “Also in 1853, the Clyde-built supply ship Breadalbane was nipped by ice off Beechey Island and sank within minutes.

“Even a seemingly minor accident could have disastrous consequences so far from help or rescue.”

The Northwest Passage is around 500 miles north of the Arctic Circle and fewer than 1,200 miles from the North Pole.

In Franklin’s time, finding it was one of the greatest maritime challenges.

The fate of the Franklin expedition fascinated Victorians and inspired a steady stream of books and a Ridley Scott TV series on BBC Two.

Gordon Morris from Dundee, played John Weekes, a carpenter on board HMS Erebus, in the chilling 10-part supernatural drama.

He said: “I was so disappointed to hear the dive season on Erebus and Terror has been cancelled, as I really want to know if any papers have survived that will give us a clue as to what happened to the crews of both ships.”